#10: (No) Room to Grow

Easing space requirements within a factory can create ~35% more jobs in India

The share of manufacturing in India’s GDP has stagnated and it has ranged from 14 to 17% for many decades now. This stagnation has attracted the attention of policymakers and at least five government schemes have been launched to boost manufacturing in India. The latest such scheme is the Production Linked Incentive Scheme which involves paying industrialists to increase production. However, at the same time, Indian laws work against increasing employment and require factories to pursue other goals. The space requirements for workers and facilities under the Factories Act are an example of such a law.

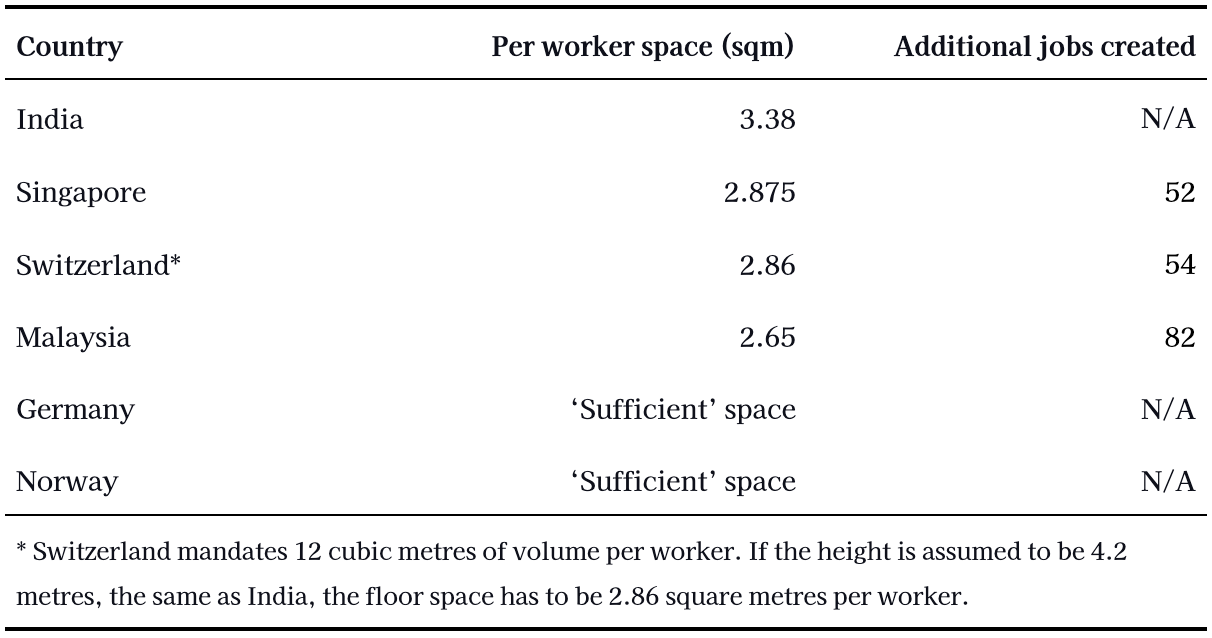

The manufacture of goods is the reason for building factories. However, Indian factories are forced by law to use land inefficiently for manufacturing. This inefficiency arises from two requirements under the Factories Act, 1948. First, the law requires a minimum floor space of 3.38 square metres per worker (Section 16). This is the highest such standard we could find in comparison to other countries. Second, the law requires factories to reserve floor space for facilities like canteens (Section 46), lunch rooms (Section 47), creche (Section 48), ambulance rooms (Section 45), latrines and urinals (Section 19), and shelter rooms (Section 47). Compared to other countries, these requirements are the highest we could find.

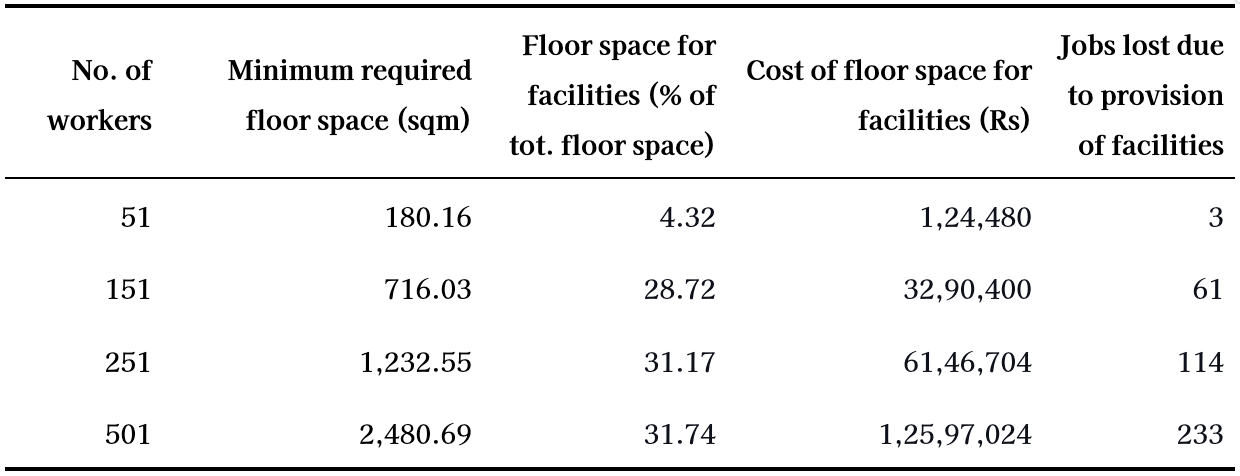

Factory floors lose a significant proportion of area to activities not related to manufacturing due to requirements set under the Factories Act. This area can be better employed to generate employment or reduce the cost of operating a factory. For example, a large-sized factory with 501 workers in Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh can employ up to 233 more workers or save ~Rs 1.26 crore worth of land. The unlocked factory floor is an underestimation because, in addition to space requirements within a factory, Indian regulations also determine how much usable space is available for a factory. Previous articles on ground coverage, setbacks, parking, and floor area ratio highlight how building standards limit usable building space on a plot.

High floor space per worker

India prescribes higher floor space per worker on a factory floor as compared to other countries. Each Indian factory has to provide at least 14.2 cubic metres of space, with a constraint that the height cannot exceed 4.2 metres (Section 16, Factories Act, 1948). This means a factory floor must provide at least 3.38 square metres of floor space for every worker. On the other hand, Switzerland, Malaysia, and Germany prescribe lower floor space per worker (Table 1).

An Indian factory with 1,000 square metres of usable floor space can, thus, employ up to 82 more workers if India were to adopt Malaysia’s standard. India can create additional jobs in manufacturing by reducing per worker space in line with the standard in other countries.

Floor space for facilities

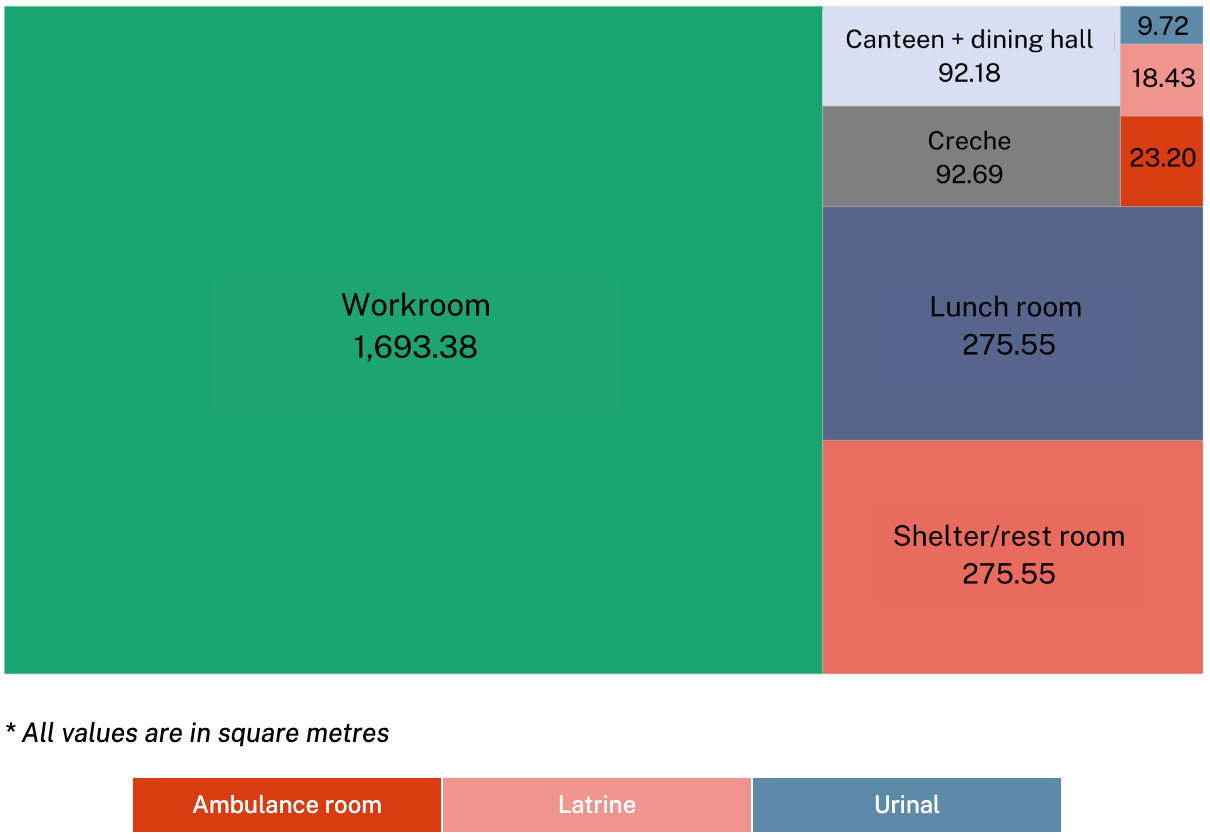

An Indian factory must also set aside space for facilities in addition to the mandated floor space per worker on the factory floor. The list of these facilities increases as the number of workers employed in the factory increases (Table 2).

In other countries, the facilities mandated are not as onerous as they are in India. For instance, factories in Switzerland are not mandated to provide an ambulance room/first-aid facility, or a creche on the premises. Canteen and restrooms should be provided ‘if required, particularly when workers do night or shift work’. Similarly, Malaysia does not impose any requirement for a creche, a first-aid facility, or a canteen. Factories in Singapore with more than 500 workers are required to provide a first-aid room, but the law does not mandate the provision of canteens, creches, restrooms/lunch rooms. Factories in Vietnam are not required to provide any of these facilities.

A hypothetical: Case for Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh

Factories lose a significant proportion of floor space to facilities mandated by law. Consider a hypothetical textile factory that employs 501 workers and is located in Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh. This factory does not require any machinery on the factory floor. However, at least 50% of workers (251) stay back for meals on the premises. Of the total employees, 20% (100) are women, and 50% (50) of the women have children under the age of six years. Such a factory will require at least 2,481 square metres of floor space. Out of this, only 1,693.38 square metres (~68%) can be used for production (Figure 1). The remaining 32% of floor space has to be kept for legally mandated facilities. This is a conservative estimate of the floor space required for facilities, given the assumption that only half of the workers opt to stay for meals on the premises.

If these facilities were relaxed, nearly 32% of the floor space (787 square metres) would become available for productive use, which could employ an additional 51% (233) workers. Alternatively, the same factory could save ~Rs 1.26 crore (Table 3).

Discouraging growth

The law on factory floors discourages the growth of enterprises in two ways. First, regulations make it cheaper to operate two enterprises with fewer workers instead of one enterprise employing more workers. Second, discontinuity in labour regulations makes it expensive for an enterprise to hire an additional worker.

Research shows that small enterprises or ‘dwarves’ dominate the Indian economy, thus, holding back economic growth and productivity (Economic Survey, 2018-19). Factories remain small by operating at the margins to stay below regulatory thresholds. The factories are discouraged from scaling up because requirements for different rooms change at different thresholds. For instance, a factory with 250 workers that hires even one more worker will have to ensure the provision of a canteen, a dining hall, two additional latrines, and one more urinal. Enterprises are, thus, forced to operate at the margins due to the discontinuity in labour regulations thresholds.

These regulations form a barrier to growth. Two 150-worker factories together need a total of 1,098 square metres of floor space. On the other hand, one 300-worker factory needs 1,512 square metres (37% more) of floor space (Figure 2). It would, therefore, be rational for a factory manager to open a new factory rather than expanding on the same factory. This creates diseconomies of scale. The absence of flexibility in the standards, thus, costs workers potential jobs. Research shows that a 10% increase in labour costs can lead to up to a 10% decrease in employment (Hamermesh, 2014).

A hypothetical: Case for Ambad, Maharashtra

The factory floor laws retard job and economic growth in another way—by making incremental growth precipitously expensive. The following hypothetical demonstrates this problem. Consider a hypothetical factory located in Ambad, Maharashtra. It has the same composition of workers in terms of ratio of male to female workers as the previous hypothetical factory in Uttar Pradesh. However, this factory employs 150 workers. Table 4 shows the space requirement for the factory if it were to hire just one more worker at different employment strengths, starting at 150 workers.

As Table 4 shows, an employer faces sudden jumps in the cost of hiring an additional worker due to the discontinuity in labour regulations. For instance, a 250-worker factory in Ambad, Maharashtra will have to spend Rs 4.46 lakh to accommodate one more worker. This is because the factory would need an additional 84.41 square metres to construct two more latrines, a urinal, and a canteen with a dining hall, to hire the additional worker.

This hypothetical case of Ambad is an underestimation because floor space is governed by other regulations too. These regulations limit the amount of floor that can be built on a given plot. In Maharashtra, this is around 50%, i.e., for every 1 unit of factory floor, the enterprise will have to buy 2 units of land. Therefore, the enterprise will have to pay twice the floor space cost (as land cost) it would have paid to provide facilities.

Non-compliance

High and inflexible standards force employers to be non-compliant. Consequently, the Indian factory floor may not look like what the law mandates. For instance, a report by the National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (2008) highlights that the average workspace was 2.79 square metres per worker in Mumbai leather accessories manufacturing, as opposed to the mandated 3.38 square metres. This de facto per worker floor space in Mumbai is close to the legally mandated floor space in other countries such as Malaysia (2.65 square metres) and Singapore (2.875 square metres). An employer can, thus, arrive at a particular per worker space that is productively efficient but different from the legally mandated worker space.

Employers who wish to scale up are forced to choose between expensive compliance or legal scrutiny in case of non-compliance. If non-compliant, enterprises may be penalised with fines or even shutdowns. To avoid expensive compliance, employers may choose to operate informally, stay small, or start discrete enterprises below the applicable thresholds. Informality further restricts employers’ access to formal credit and makes it difficult for Indian enterprises to compete globally.

Minimal changes in new Labour Codes

India will soon introduce the Occupational Safety, Health, and Working Conditions (OSHWC) Code, which will replace the Factories Act and aims to ease compliance burden for enterprises. However, the Code may fall short of achieving the intended objectives. Indian factories will face similar space regulations with the introduction of the OSHWC Code. The Code proposes the same kind of space standards and facilities (Section 24, Chapter VI of the OSHWC Code) as the Factories Act.

Not much changes in terms of facilities’ thresholds in the OSHWC Code. The same thresholds apply for requirements such as canteens and ambulance rooms as in the Factories Act. The only improvement is seen in the provision of creches. Under Section 24(3) of the Code, the government has allowed the pooling of creche facilities for different factories.

Enterprises may actually be worse off with the introduction of the OSHWC Code. In certain instances, the Code has reduced thresholds at which requirement for facilities kick in. Smaller enterprises, thus, need to provide more facilities for workers. For instance, the OSHWC Code (Section 24(2)(iii)) requires factories with more than 50 employees to provide shelter or restrooms, as opposed to the threshold of 150 employees under the Factories Act.

Workers lose out

The floor space used for facilities may in turn be hurting the workers’ interest, because the requirements increase the cost of employing workers. An enterprise may adjust the cost spent on providing facilities by reducing workers’ wages. An enterprise has to distribute the costs of production among three major inputs—labour, capital, and raw materials. Expenditure on capital input increases as more facilities are to be provided. To remain competitive, an enterprise may only be left with the choice of reducing workers’ wages since the prices of raw materials and factory output are usually determined globally.

The current regulations ignore that an employer already has an incentive to provide different facilities without a legal mandate. This is because an employer knows that by providing facilities such as urinals, lunch rooms, etc., he can ensure that the majority of a worker’s time is spent on the factory floor. An enterprise’s productivity may fall if workers do not have facilities in the vicinity of the workplace. The absence of these facilities may disrupt the time spent by a worker on the factory floor, which harms an enterprise’s productivity. An employer will, therefore, likely provide facilities in or near the factory premises.

Conclusion

India’s focus on manufacturing requires maximising the spaces that can be dedicated to productive use. To this end, India’s labour regulations need to reduce the proportion of floor space set aside for space standards and facilities. One possible strategy is for factory clusters to pool different facilities and use them as a shared service which will help unlock more land for productive use.

Space regulations make industrial land expensive in India. Indian regulations provide facilities to existing workers without considering the alternatives available to the remaining workers who may remain unemployed. Policymakers should therefore assess the alternatives a worker might have to bear before mandating standards that are onerous for an enterprise to fulfill and disadvantage the workers instead of benefiting them.

References

Hamermesh, Daniel S. (2014), Do labor costs affect companies’ demand for labor?, IZA, World of Labor.

Ministry of Commerce & Industry (August 2023), Production Linked Incentive Schemes for 14 key sectors aim to enhance India’s manufacturing capabilities and exports, Press Information Bureau.

Ministry of Finance (2019), Economic Survey of India 2018-19, Government of India.

National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised Sector (2008), Report on Conditions of Work and Promotion of Livelihoods in the Unorganised Sector, Academic Foundation.

Steiner, Jon (2011), The art of space management: Planning flexible workspaces for people, Journal of Facilities Management.

UN Global Compact, A safe and healthy working environment.

Eknoor Kaur, Sirjan Kaur, and Shubho Roy are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Bhuvana Anand, Abhishree Choudhary, Suyog Dandekar, and Sargun Kaur for their contribution.