#1: Losing Ground

Part 1/5: States can unlock 25-60% of factory land for productive use by easing ground coverage limits

Industrial/commercial land in India is scarce. This scarcity is not a result of unavailability of land but of laws and regulations that suppress a functioning market for land. In such a scenario, the nation must use the little land available to it efficiently. How Indian states vary restrictions on buildings, and the cost of such restrictions will be the subject of Prosperiti’s upcoming State of Regulation report.

One restriction on efficient use of land is permissible ground coverage that limits usable space on a plot. As per ground coverage regulations, industrialists cannot use a significant portion of the plot for the factory building. Across India, a manufacturer can lose 25-60% of the plot depending on the state and other conditions.

This loss of land, due to regulations, imposes costs on society because industrial activity cannot be carried out on the entire plot. This in turn means fewer jobs, lower income, and wasted resources. Economic activity may be increased by rationalising ground coverage regulations.

Textile manufacturing: A hypothetical

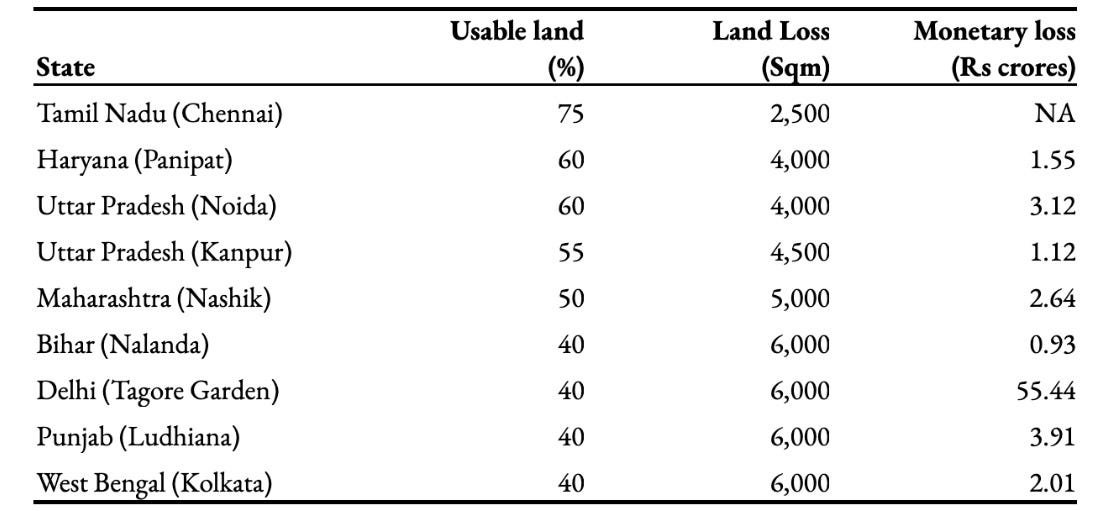

Consider a hypothetical textile manufacturer that buys a 10,000 sqm plot in an Indian state. In this scenario, the manufacturer plans to set up a 20m tall factory building that will release some pollutants. 18 laws across 9 states were studied to collect ground coverage requirements to calculate land loss. Similarly, the monetary loss was calculated using circle rates. The following table shows the loss in area and money for such a hypothetical factory across states.

The textile manufacturer will lose the most land in Delhi, Bihar, West Bengal, and Punjab, but the monetary loss will be the highest in Delhi, followed by Punjab (Ludhiana), and then Uttar Pradesh (Noida). Delhi is an outlier because of the high price of land. In contrast, some countries do not impose such high ground coverage limits like India. For example, in Hong Kong, the hypothetical manufacturer will be able to use 95% (9,500 sqm) of the land.

Penalising success

States, in effect, penalise larger industries. In many states, low-rise buildings or smaller plots get relaxed ground coverage norms. For example, Uttar Pradesh allows an additional 5% ground coverage to some factories that are less than 450 sqm. Punjab allows an additional 25% of ground coverage to factories that are less than 15m tall. States may have relaxed these restrictions to encourage small industries, but the result is when factories expand, they are punished.

Return to central planning

Some state governments implement industrial policy through ground coverage rules. For example, Haryana allows apparel, footwear, and data centres an additional 20% usable land. This rule creates bias for the three industries, at the cost of all other industries. Haryana, by picking winners, is probably losing jobs, wealth, and taxes from industries that the government has not imagined. Similarly, Punjab offers an additional 5% ground coverage to the retail service industry, thereby losing economic growth from other industries that don’t get the benefit.

Indian complexity

A standard ground coverage restriction may have been easy to follow. However, states use multiple criteria to determine the actual requirement such as plot size, type of industry, building height, location, etc. For example, some industries in West Bengal and Tamil Nadu face limits on usable plot area in 10 different tiers. In Uttar Pradesh, this number is 36.

Argument for reform

Literature argues for ground coverage restrictions for four reasons—(i) limit building density; (ii) encourage groundwater recharge; (iii) increase green cover; and (iv) safety and decongestion. However, a deeper consideration shows that these reasons may be misguided, solved by better technologies, or addressed by specific regulations.

States seem to prefer low-density buildings for better handling of urban infrastructure, environment, and economic growth. However, density control actually harms all three. Higher density promotes more efficient use of land resources by bringing buildings closer and reducing urban sprawl. It also makes it easier for workers to access job centres, reducing transportation costs and attendant pollution. Research also shows positive economic benefits of higher density like increase in labour productivity (Ciccone and Hall, 1996), and higher innovation (Carlino et al., 2006).

Regulations limit building footprints to facilitate groundwater recharge through rainwater seepage. However, rainwater harvesting technology can achieve better results without wasting usable land, and laws already mandate the use of such technology. For example, in Punjab, all industrial plots above 100 sqm must construct a rainwater harvesting system. This makes ground coverage restrictions for groundwater recharge redundant.

In addition, laws limit ground coverage to encourage tree planting. For example, some states require large-scale industrial projects (5,000 sqm and above) to plant a minimum of one tree per 100 sqm. Ostensibly, this regulation is targeted at creating green cover. However, the environment may be better served by allowing high-density building development surrounded by large contiguous green cover. Planting 100 trees with high density on a small plot of land is more beneficial than planting 100 trees spread out along the boundary of the plot. States could offer high ground coverage to industries located next to each other, and create green cover surrounding such areas.

Some argue that ground coverage limits reduce the probability of fire spread and provide space for parking and movement. However, states already mandate separate standards to address safety and decongestion requirements. For example, Noida requires our hypothetical factory to leave margins of 9 m, 6 m, and 6 m on front, rear, and sides for fire protection. Similarly, the factory will also be required to create 130 parking spots for cars, and cycles.

Industries may lose more than half of their plot area to ground coverage limits. This area can be unlocked for productive economic activity by regulatory change.

References

Ashwani, K. (2012). Building regulations: a means of ensuring sustainable development in hill towns. Journal of Environmental Research and Development, 7(1A), 553-560.

Carlino, G. A., Chatterjee, S., & Hunt, R. M. (2007). Urban density and the rate of invention. Journal of Urban Economics, 61(3), 389-419.

Ciccone, A., & Hall, R. E. (1993). Productivity and the density of economic activity.

Patel, B., Byahut, S., & Bhatha, B. (2018). Building regulations are a barrier to affordable housing in Indian cities: the case of Ahmedabad. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 33, 175-195.

Shubho Roy and Sargun Kaur are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Bhavna Mundhra and Anandhakrishnan S from Prosperiti for painstakingly mining and analysing the regulations.

Great write up. A few follow up questions:

1. How do the ratios for various Indian states compare to regulations in countries / states in other countries? Say, Vietnam, Mexico, China, etc.?

2. Which ministry or ministries do ground coverage ratios tend to fall under? I'm wondering because the subject is industry, but the justifications seem to relate to (a) urban affairs / municipal planning ; (b) ministries of water resources; (c) environment and climate change ; (d) road and transport.

3. So a second part of the second question relates to the mechanisms by which different departments are able to share knowledge; e.g., if 'Planting 100 trees with high density on a small plot of land is more beneficial than planting 100 trees spread out along the boundary of the plot' is true, then how would that expertise inform choices by the industrial ministries?

Great Article Team!

Interestingly in my reading of the Punjab Building Rules it seems allowing for higher GCR is not always possible given how other clauses in the rules are drafted. The ECS scale with buildable area and create an implicit constraint that pulls back on available land area. While the open space restrictions + the setback norms create a hard topline restrictions that need to be met.

In case of Punjab specifically bringing parity between the GCR norms for high rise vs low rise Industries is not possible given existing norms for parking, setback and open space. A GCR higher than ~55% , in the case of high rise industries, without changing other norms would trigger other violations making the factory non compliant. Hence the lower GCR becomes a necessity for high rise Industry rather than a deliberate penalty that the government is levying on growth.

In our analysis what truly affects vertical industries like apparel is a combination of high ECS norms and the NBC height restrictions (for fire regulation). Based on our analysis just relaxing these two norms can 2x our buildable space without us ever needing to increase the GCR norms. But increasing the GCR without fixing for these two norms will at the most give us an increase of ~35%. If we can unlock all three simultaneously then we can more than 3x our buildable space!

Happy to engage further on this in person - Ronak Pol (Foundation for Economic Development)