#4: Stunted Growth

Part 3/5: Each commercial building in Indian cities can employ 5 times more people by liberalising the floor area ratio requirement

Unaffordable Commercial real estate

Renting an office space in India is costlier than many of the other major cities in East Asia. The demand for office spaces is on the rise; affordable supply of spaces is imperative to keep rents in check and thus, enable growth of business. One factor that affects the affordability of office spaces is the available floor area. One way through which states regulate the creation of office spaces is through “Floor Area Ratio” (FAR) (also referred to as Floor Space Index) which puts a limit on the floor area that can be built in a given piece of land.

In previous articles, we examined the implications of ground coverage and setback regulations on the buildable space within a plot. These regulations determine the maximum area of a given plot that can be utilised for constructing a building. In addition, states use FAR to limit how tall a building can be constructed which consequently controls the floor area of the building. This has an impact on the affordability of spaces and the possible economic outcomes.

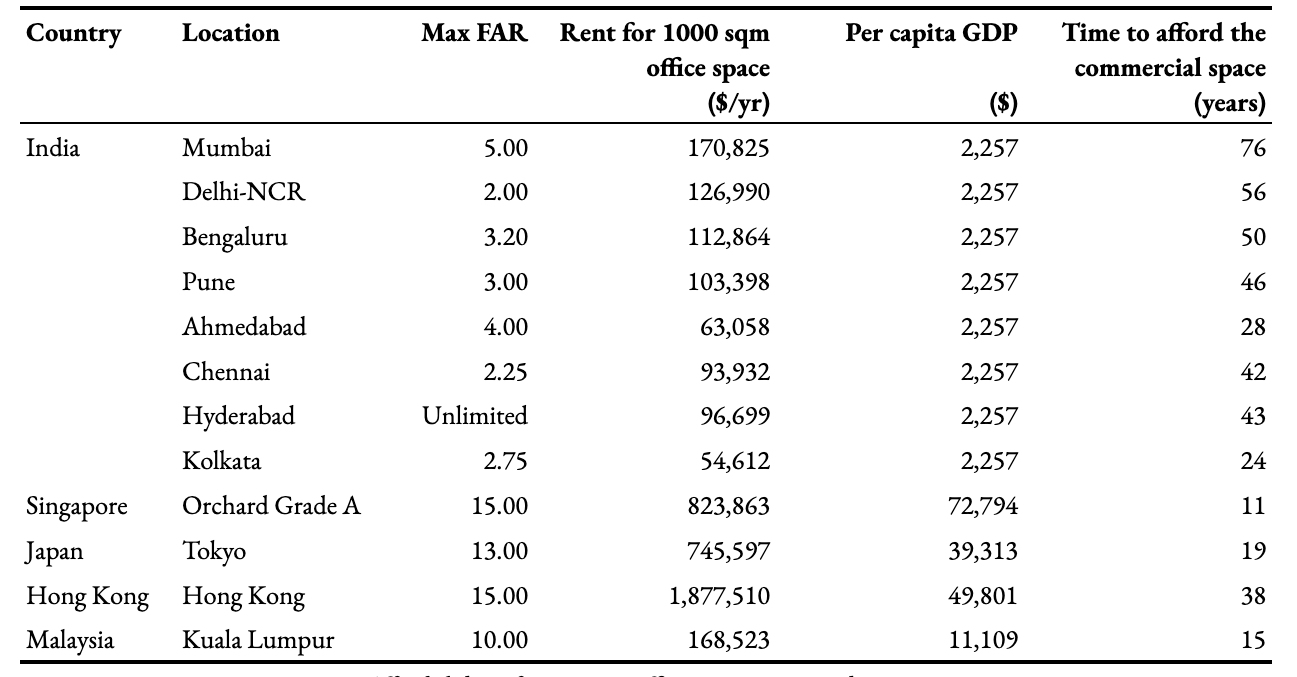

Office space in India is relatively more unaffordable than countries in the region. In absolute terms, office space in India is cheap with only Malaysia being cheaper. However, Indians on average are much poorer than most other countries in Asia. So, a better measure is to convert rental value as a multiple of per-capita GDP. With this measure, India comes up as the most unaffordable. Consider an office space with 1,000 sqm floor area on a given piece of land located in various Indian cities and some East Asian countries. The following table shows the number of years it will take for an entity to afford the rent of such a space, as derived from the per capita GDP of the country.

The average years required to afford the sample office space in Mumbai is 76 years which is almost 7 times that of a similar space in Orchard Grade A (Singapore), 5 times that of Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia) and 4 times that of Tokyo (Japan), making India the most unaffordable in terms of rent per capita GDP.

This unaffordability is due to the artificial shortage of office space, brought on in part by the regulation on FAR. Limiting office space supply in this way is akin to imposing production quotas on industries. The production quotas of the License Raj era are today widely panned as harmful to the growth of the economy. Just like production quotas, regulation on FAR hampers economic growth by distorting the market for commercial space and housing. For instance, research shows that the presence of such regulations makes housing unaffordable in India (Rajagopalan et al., 2019). Exorbitantly high rents are the consequence of these market distortions.

The high cost of rent in India will have negative economic consequences because other inputs to production will have to compensate for the high rent through lower returns. This is because most goods and services have a global price today; if one of the inputs is more expensive in India, then other inputs must be made cheaper to keep costs competitive. In such a situation, labour costs in India will have to be lower to compensate for the higher real estate costs.

Another way to look at this problem is in terms of employment potential. India’s low FAR reduces the number of people that can be employed per unit of the plot area. Industry has estimated the average space needed for a generic white-collar job to be ~ 14 sqm per office worker. Therefore, more workers can be employed on the same plot if the building can be taller. The following table compares the number of workers that can be employed on a 1,000 sqm plot in different cities in India and some Asian cities.

As the table above shows, a standard plot has the lowest employment potential in India. On average, in India, a 1,000 sqm plot employs only 228 persons. The same plot in Tokyo can employ 935 people, and for Singapore, the job tally is 1,079.

Arguments for low FAR

Planning authorities try to prevent traffic congestion and ease the supply of utilities such as water and electricity, by artificially restricting allowed FAR. Due to low FAR, buildings cannot grow vertically, and the same population spreads out horizontally to occupy a larger geographic area. As a result, the population density of a given area falls when FAR is limited. Low population density, according to planning authorities, helps in preventing congestion and reduces pressure in providing utilities. However, regulation of FAR may be causing the opposite effect (Abraham et al., 2020).

Planning authorities think that there will be less congestion if there is low population density because fewer people will lead to fewer vehicles on the road in the area. However, counter-intuitively, research shows that the density of an area does not have any effect on traffic congestion (Ewing et al., 2018). This is because low density increases the distance between the source and destination and thus increases the travel time. Consequently, vehicles spend more time on roads, leading to congestion. For example, the average commute time in Mumbai is double that of Hong Kong and Singapore though they have higher densities compared to the Indian city.

Another way congestion may increase because of low FAR is by making public transport financially infeasible. Public transport usually reduces congestion because the road area occupied per commuter is significantly lesser in public transport (like buses and trains) as opposed to individuals in cars. However, low population density (due to low FAR) makes public transport financially unviable as the number of potential passengers per unit area is lower when density is lower. Therefore public transport has to travel longer distances to collect the same amount of passenger fees. As an example, researchers have argued that low-density housing in New Delhi has contributed to the low use of the Delhi Metro.

There is another reason why planning authorities limit population density through restricting FAR. Authorities think this will ease the supply of utilities in an area as lower density will lead to lower demand on utilities (like water and electricity). While this is true for the small area, overall the cost of providing the utilities increases when FAR is low. This is because utilities have to service a larger area as the population is horizontally spread out. The larger area requires more pipes and wires and leads to more transmission loss. In extreme cases, entirely new sets of utility-generating units may be needed because the population is sparsely distributed.

Economic harms of low FAR

In addition to not mitigating the problems that the planning authorities try to solve, low density as a result of FAR causes other economic harms. Three effects that have been identified are: reducing the job market, reducing income, and preventing urban renewal.

Literature shows that an effective labour market and economy grow when a large number of jobs are accessible within a certain commute time (Bertaud.A, 2014). As low-density increases commute time, jobs are affected. For the jobs that are available, low density reduces the effective income of households by increasing the cost of commute. For example, urban sprawl due to FAR has resulted in a loss of 1.5% to 4.5% of household income in Bangalore for commuting (Vishwanath et al., 2013).

Authorities, by limiting FAR, may also be hampering urban renewal. Old buildings are usually more inefficient and are ill-adapted to modern technology. Breaking them down and renovating them is costly. This cost is usually offset by building more floor area when renewing buildings. However, increased floor area is artificially limited through FAR regulations. This makes urban renewal projects financially unviable and the city is left with many energy inefficient old buildings in the centre of the city where property prices are usually high. These city centre plots are economically valuable as they are well-connected and have better access to utilities. However, regulations like FAR prevent their efficient economic use (Sreedhar K.S, 2010).

An Indian exception

The city of Hyderabad is an exception to the low FAR regulations. In 2006, the government removed the limits on FAR in some of the city’s commercial areas and reports suggest that commercial buildings are recording FAR between 9 to 13 in the city. However, the planning authorities’ concerns have not played out in Hyderabad. Commute time in Hyderabad, according to reports, is less compared to other India cities such as Mumbai, Bengaluru and Delhi. Furthermore, there are also no reports of any excessive shortage of utilities in the area as planning authorities fear.

Arguments for reform

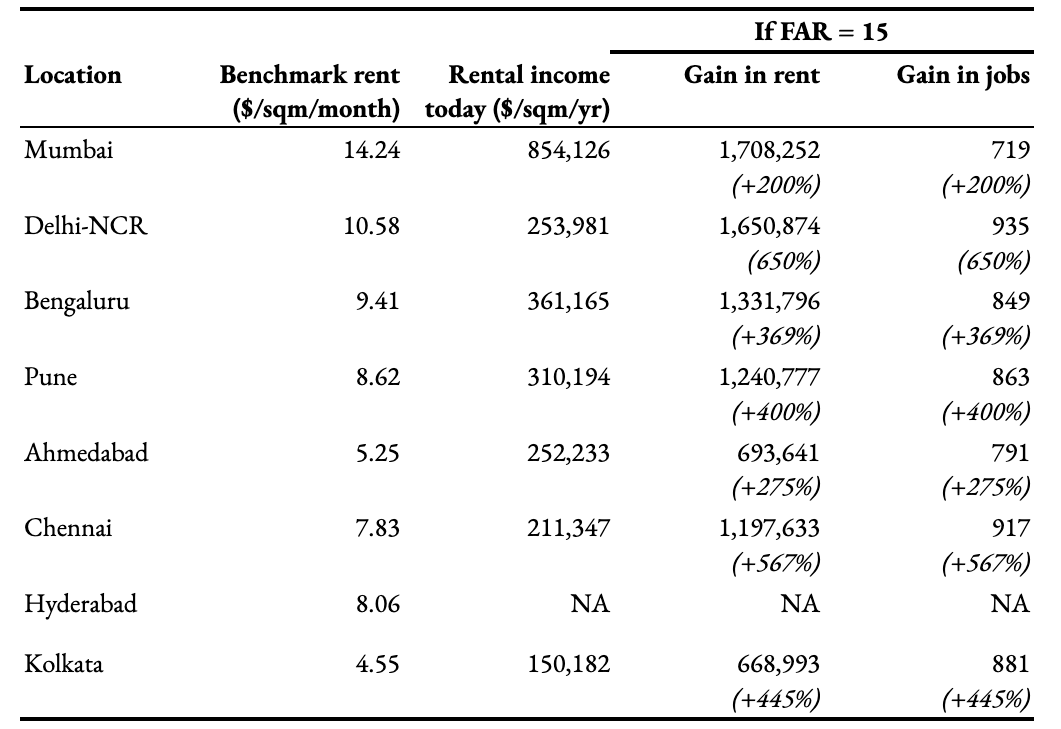

Indian states can foster economic activity and increase employment by relaxing FAR limits. The increased floor area, freed from regulation, can generate economic activity and employment, and make commercial buildings cheaper. The following table continues with the example of a 1,000 sqm plot and estimates the gains in rental income and jobs if Indian cities increased FAR to 15 in line with some exemplar Asian cities.

From the table, a commercial building in Mumbai can gain approximately 1.7 million USD in rental income and employ an additional 719 people if the FAR was 15. On average, across all the cities we consider here, there can be 5 times gain in both the rental income and in the number of people who can be employed if the FAR was 15. This estimate is meant to illustrate a way of thinking about the opportunity costs of regulation.

Indian states can improve economic activity and employment opportunities by leaving FAR to commercial considerations. Compared to planning authorities, builders are generally in a better position to anticipate the needs of the market and adapt to the infrastructural constraints.

References

Abraham, R., Hingorani, P. (2020). Fix the issues that plague the Indian housing market. Hindustan Times.

Bertaud, A. (2014), Cities as Labour Markets, Working Paper, Marron Institute of Urban Management

Ewing, R., Tian, G., Lyons, T. (2018), Does compact development increase or reduce traffic congestion?, Portland State University

Rajagopalan, S., Tabarrok, A. (2019), Premature Imitation and India’s Flailing State, The Independent Review, 24(2): 165-186.

Sreedhar, K. S. (2010), Impact of Land Use Regulations: Evidence from Indian Cities

Vishwanath, T., Lall, S. V. , Dowall, D., Lozano-Gracia, N., Sharma, S. & Wang, H. G. (2013), Urbanization beyond Municipal Boundaries: Nurturing Metropolitan Economies and Connecting Peri-Urban Areas in India, The World Bank

Anandhakrishnan S, Bhuvana Anand, and Shubho Roy are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Sargun Kaur and Bhavna Mundhra for painstakingly mining and analysing the regulations.