#9: Parking Reserved

Part 4/5: Easing parking requirements can unlock up to 45% of the productive factory area

Industrial/commercial land in India is scarce. This scarcity is not a result of unavailability of land but of laws and regulations that suppress a functioning market for land (Byahut et al., 2020). Previous articles on ground coverage, setbacks, and floor area ratio highlight how building standards limit usable building space on a plot. The remaining usable plot is further restricted by minimum parking requirements.

States mandate the number of parking spaces required for different vehicles and the area required per vehicle. Across India, manufacturers may lose up to ~45% of their land to meet minimum parking requirements.

Provision of free off-street parking is a loss for enterprises as the land is unproductive, and there is no way of being able to recover the cost. This land could have been used to create additional jobs, income, and revenue for state governments.

Textile manufacturing: A hypothetical

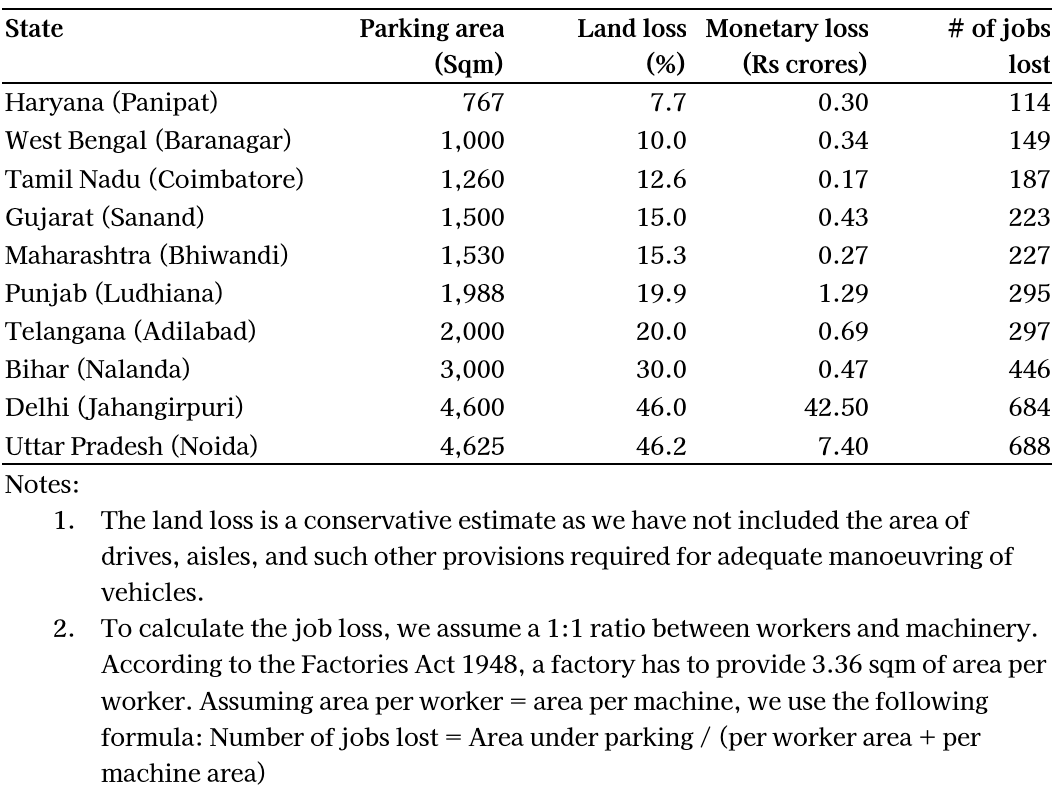

Consider a textile manufacturer who buys a 10,000 sqm plot in an Indian state wanting to set up an 18 m tall factory building that will release some pollutants. The following table shows the loss in area, value of land, and jobs for such a hypothetical factory across states.

Haryana’s parking minimums are the most progressive in the country. The next most business-friendly state is at least 30% more demanding than Haryana. The least business-friendly state in this respect is Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh’s parking norms are at least 6 times more restrictive than Haryana’s.

The only way a firm can meet the parking minimums while maximising jobs on the floor is by constructing a separate parking building. But, constructing a parking building is an added cost, and affects the competitiveness of an enterprise.

International competitiveness

The minimum parking requirements for industrial buildings are high in India compared to Asian countries.

Even the best-performing state in India—Haryana—mandates at least twice the car parking spaces for industrial buildings compared to Singapore, Hong Kong, and Philippines. Loading requirements in Noida (Uttar Pradesh) are the most egregious at 7 times that of Hong Kong. Tamil Nadu is the only state in India that recognises that parking requirements for workers may be different than managerial staff. A factory of this size in Tamil Nadu can save 5% of plot area because of this regulatory flexibility. The challenge is no different for commercial buildings. Barter (2010) compares the parking requirements for commercial buildings across major cities in Asia, and finds that Ahmedabad prescribes higher parking minimums for commercial buildings as compared to Tokyo, Beijing, Singapore, Dhaka, and Hong Kong.

India’s regulatory minimums amount to a higher parking space per worker compared to other Asian countries. A factory in Noida, Uttar Pradesh will need to allocate 9 times more parking area per worker than in Hong Kong, a jurisdiction 5 times larger and 12 times more densely populated.

Argument for reform

Indian states should consider rationalising minimum factory parking requirements to account for actual demand, facilitate decongestion, and promote high-density development.

Parking mandates are not set based on actual demand in industrial buildings, and hence, may need to adjust for reality. Data shows that less than a third of Indian workers travel via such modes of transport (like car, cycle, and scooters) that require parking (Census, 2011). The proportion varies between 27-40% across states. Parking minimums however vary dramatically. In fact, even in states where fewer workers require parking for their vehicles, the parking minimums tend to be inordinately high. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra firms have to set aside 3 times more parking minimums than Haryana, even though fewer workers may require parking, i.e. 28% and 26% versus 31%. The current minimums also do not account for rapidly changing modes and preferences of transportation. For example, low-cost, on-demand taxi services, and ride-sharing services have exploded in the past 10 years (Rosenblum et al., 2020). Parking minimums inevitably require an entrepreneur to invest in permanent structures. Other than demolishing this structure, the entrepreneur has no choice but to keep the earmarked land fallow to comply with the mandates. Thus, parking minimums are likely to lead to a dead-weight loss of land for a factory given the absence of parking demand studies.

Parking mandates may be contributing to congestion even though they were instituted to alleviate crowding. More buildings with mandated parking incentivise more cars on the road. But, the supply of driving space and good quality road infrastructure cannot be rapidly expanded to keep pace. Singapore, despite being a high-density, space-constrained location, mandates low parking minimums while offering good road network and connectivity. Contrastingly, India’s road infrastructure especially within cities is congested, and offers low connectivity. This mismatch could exacerbate congestion and impact central business districts, undercutting the economic advantages of high density as the resulting congestion renders these areas less accessible (Manville & Shoup, 2018).

Finally, and worst of all, minimum parking requirements may deter the growth of high-density development. High-density compact development encourages shorter commute times for workers and reduces transport costs (Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation Guidelines Volume 1, 2015). Flatted factories, i.e. tall stacked manufacturing facilities, are a feature of high-density environments such as Singapore. Singapore prescribes higher parking minimums for a flatted factory compared to a single-detached manufacturing unit. Even so, these requirements are 23% lower than India’s most progressive state. As they stand, parking requirements in India are inimical to the proliferation of flatted factories and consequent high-density development.

To facilitate ease of doing business, states can consider substituting parking minimums and experiment with selective exemptions. For instance, Japan’s minimum parking requirements are set very low and exempt small establishments (Barter, 2010). Palo Alto in California offers developers the opportunity to pay a regulatory fee in lieu of providing the mandated parking (Shoup, 1999). These alternatives can offer firms and developers the flexibility to respond to competitive needs.

Indian states do not offer competitive parking minimums, leading to loss of a significant portion of productive land. Rationalising parking requirements can unlock precious land, and contribute to India’s prosperity.

References

Barter, P. A. (2010). Parking Policy in Asian Cities (SSRN Scholarly Paper 1780012).

Byahut, S., Patel, B., & Mehta, J. (2020). Emergence of sub-optimal land utilization patterns in Indian cities. Journal of Urban Design, 25(6), 758–777.

Manville, M., & Shoup, D. (2018). People, Parking and Cities. Journal of Urban Planning and Development, 131, 233–245.

Rosenblum, J., Hudson, A. W., & Ben-Joseph, E. (2020). Parking futures: An international review of trends and speculation. Land Use Policy, 91, 104054.

Shoup, D. C. (1999). In Lieu of Required Parking. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 18(4), 307–320.

Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation Guidelines Volume 1. (2015).

Bhuvana Anand, Sargun Kaur, and Anandhakrishnan S are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Shubho Roy for his additional input and Bhavna Mundhra for painstakingly mining and analysing the regulations.

The previous version of this article had one factual error that has since been corrected.