#2: At the Margin

Part 2/5: States can unlock 5–60% of factory land for productive use by liberalising setback requirements

Manufacturing is hard in India. India may have missed the industrial revolution because of multiple restrictions on capital, labour, and land. One such restriction on land use is called setback requirement that forces businesses to keep a significant portion of an industrial plot unused. As a result, economic activity is lost, jobs are not created, and the country’s growth is stifled. States can increase wealth by removing such restrictions on usable land. How restrictions on land usage for constructing buildings vary across Indian states and the cost of such restrictions will be the subject of Prosperiti’s upcoming State of Regulation report.

The previous article focused on ground coverage regulations that limit usable building space on a plot. In addition to ground coverage, a usable plot is further restricted by setback requirements. These requirements force builders to leave margins from a plot boundary, limiting the size of a building. Across India, a builder can lose 5–60% of a plot to setback requirements, depending on the state and features of a building.

Land is scarce and, consequently, costly. In addition, building standards seldom take into account the cost they impose in terms of jobs uncreated and resources unutilised. Economic activity may be increased by rationalising setback requirements.

Textile manufacturing: a hypothetical case

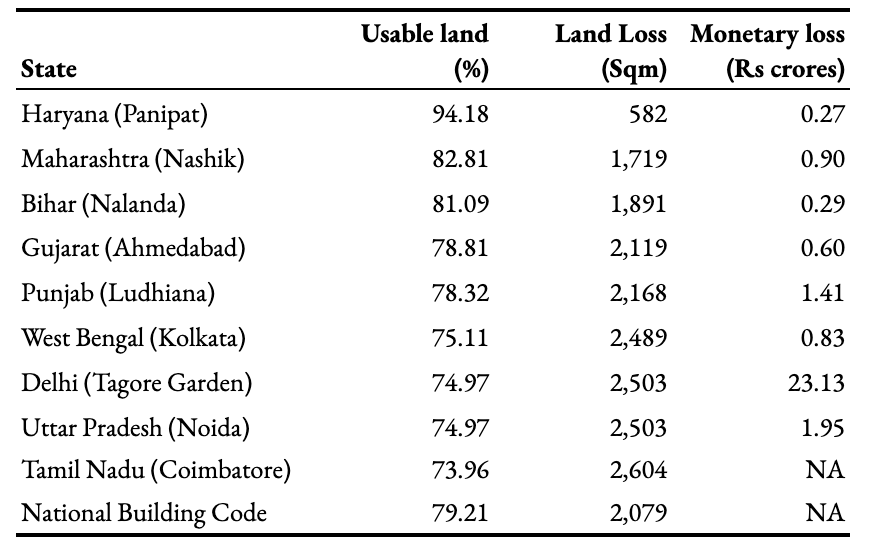

Consider a hypothetical textile manufacturer that buys a 10,000 sqm plot in an Indian state. The manufacturer plans to set up a 20 m tall factory building that will release some pollutants. 18 laws across nine states were studied to calculate land loss due to setbacks and its monetary cost. The monetary cost was calculated using circle rates. The following table shows the loss in area and money for such a hypothetical factory across states.

As the previous table shows, there is significant variation in the loss of usable land in Indian states for the same factory. The hypothetical manufacturer will lose the most land in Tamil Nadu, followed closely by Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. The monetary loss would be the highest in Delhi, followed by Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal. Delhi is an outlier because of its higher circle rates than other states. Haryana allows the manufacturer the largest usable area of all nine states.

India as a whole renders more land useless on industrial plots than other countries. Singapore is a country with high legal and safety standards. However, even Singapore allows a larger area of a plot to be put to productive use. On average, an Indian manufacturer will lose ~20% of a plot to setback regulations. In contrast, consider the same manufacturer in Singapore using an industrial plot surrounded by industrial buildings on three sides. In such a scenario, the Singapore manufacturer will lose only 5% of the plot to setback regulations. In India, only Haryana has setback losses similar to Singapore’s.

Penalising small players

Due to setback requirements, small factories are penalised more than large factories because they lose a larger proportion of usable land. This is a result of regulations using plot size to determine setback requirements. Manufacturers have to leave more land for setbacks as the size of their plot increases, but only up to a certain threshold. A plot below that threshold loses a larger proportion of the land to setbacks than a plot above the threshold. For example, in Gujarat, a 1,000 sqm plot will lose 44% compared to a plot 10 times larger (10,000 sqm) that will lose only 21% of the plot. The following table shows this size bias in nine Indian states.

Unnecessary complexity

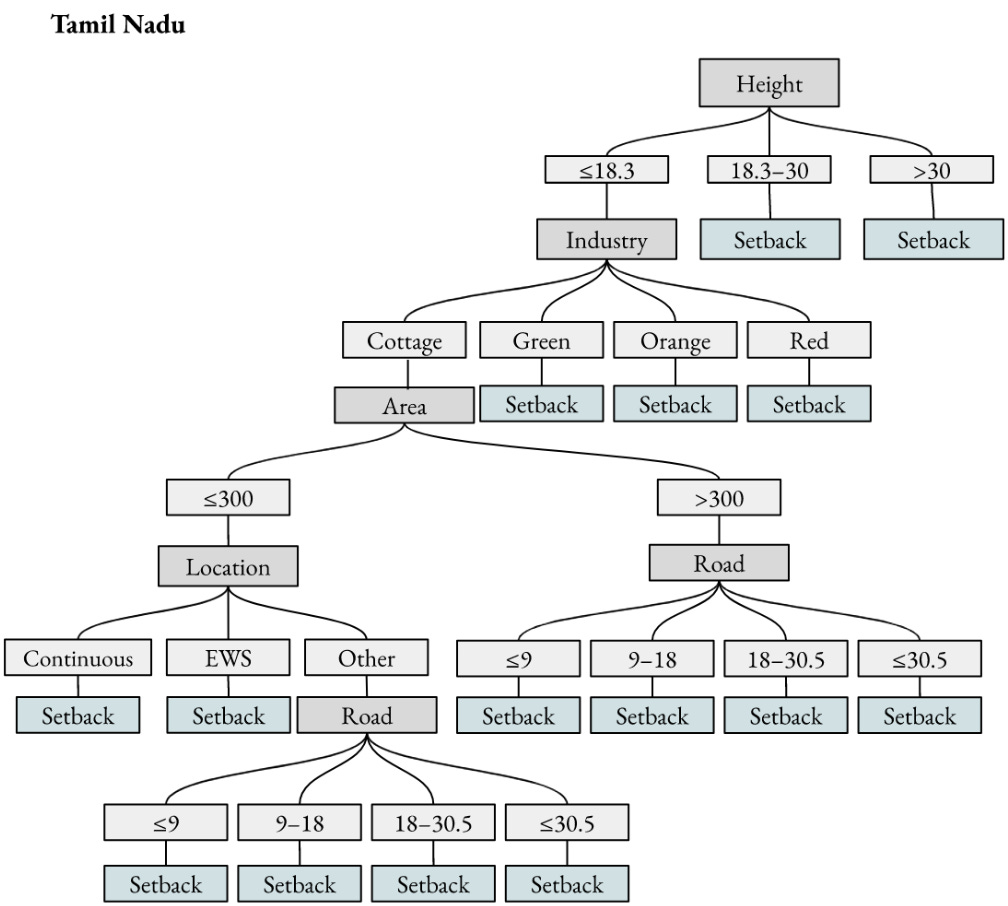

In addition to losing land, Indian building regulations may be unnecessarily complex. The regulations use multiple variables to determine setback requirements such as plot size, plot width, type of industry, building height, location, etc. In addition to the variables, Indian regulations use multiple conditionalities on how these variables interact to determine setbacks. This results in complex decision trees with multiple levels and variables. On the other hand, some countries use fewer variables and conditions, leading to simpler regulations. For example, the following figures show the contrast between Tamil Nadu and Singapore in determining setbacks.

Tamil Nadu uses five variables, ultimately making the setback value any one of 15 possibilities, while Singapore uses only two variables.

Return to central planning

In some Indian states, land taken away under setback is dependent on the nature of economic activity, leading to the government recreating central planning through these regulations. Governments favour some industries by reducing setback requirements that allow manufacturers to use a greater proportion of a plot. For example, consider a hypothetical industrial building of height 15 m on a plot of 10,000 sqm. In Punjab, this building will lose 2,300 sqm of the plot to setbacks if the building is used by the IT industry. However, every other type of industry will lose only 1,700 sqm. In effect, this is a 35% penalty on the IT establishments. This may occur even if the fire risk in the IT industry is the same or lower than other industries such as accounting for instance.

Similarly, Tamil Nadu uses pollution-based classification to differentiate setback requirements between industries. However, the relationship between the polluting nature of an industry and the minimum land a factory must leave to setbacks may be tenuous, as the excess land does not mitigate pollution or its effects. Under a similar scenario (a 15 m tall building on a 10,000 sqm plot), a handloom weaving industry will lose 1,400 sqm of the plot to setbacks, while an apparel manufacturing industry will lose only 900 sqm of the plot, a 55% penalty for the handloom weaving industry.

Such preferential treatment based on state-selected industries harms the state’s economy in multiple ways. The state may not correctly predict successful industries and thereby stymie economic growth in industries with greater productive potential. Similarly, differing setback requirements will make industrial change more difficult. An apparel manufacturer in Tamil Nadu may realise that handloom has more profit opportunities. However, a change in industry may require the manufacturer to rebuild their entire factory, where a relatively easy retrofit would have been enough. Trading in industrial buildings also becomes difficult with industry-based setbacks, as the seller and buyer may be in different industries with different setback requirements.

Arguments for reform

Literature argues for setback requirements for three purposes: (i) to minimise the risk of fire spread between buildings; (ii) to ensure adequate ventilation and admission of sunlight in a building; and (iii) to provide space for future road widening (Edwards and Torcellini, 2002; Cicione et al., 2021; Horne, 1968). However, most of these concerns can either be addressed through technological advancements or without losing productive land.

Fire risk is used as an argument for setback requirements, as it takes longer for fire to spread from one building to the next if there is some distance between buildings (Cicione et al., 2021). However, fire safety can be ensured without imposing the deadweight loss of unused land between buildings. These regulations were introduced when fire safety technologies were not advanced. Modern technologies like automatic firefighting equipment, smoke detectors, fire-resistant building materials, etc. can help reduce the risk of fire hazards without locking up productive land. Some countries, like Singapore, allow factory buildings to touch each other by building up to the property line. In other countries, buildings can be built closer if they are fire-proof. For example, Germany allows a 37.5% relaxation in setback requirements if buildings have fire-resistant roofs. The UK uses the fire resistance of building walls as a variable to determine setback requirements (Lee et al., 2021).

There is a larger question of the necessity of setback regulations for fire safety. Manufacturers may not need coercion (through regulations) to take steps to protect their investments. Standard regulations ignore the variations in fire risk arising from different industrial activities and the level of precautions taken by manufacturers. Were manufacturers left to make their own determinations, the outcomes may be more optimal. Some manufacturers may keep more than the required setback while others may build up to the property line. Singapore’s freedom from setbacks does not seem to contribute to higher rates of industrial fire spreads.

Apart from fire risk, some argue that adequate natural light and ventilation in buildings is necessary to boost workers’ productivity and reduce the cost of electricity (Horne, 1968; Edwards and Torcellini, 2002). But this thinking may be incorrect because the studies on the benefits of natural light and ventilation (Hawthorne studies from 1924–1933) have been shown to be wrong due to incorrect experiment designs. Additionally, many modern manufacturing processes need to avoid natural light and ventilation. For example, industries like chemicals, pharmaceuticals, electronics, food, etc. must be carried out in artificial lighting, or air-conditioned buildings, or both. However, Indian regulations on setbacks provide no exemption to such industries indicating that the scientific need for ventilation and lighting is not motivating these regulations. Similarly, lighting costs have significantly fallen since the 1920s when lighting was produced by incandescent bulbs that wasted most of the electricity and produced more heat than light. Today, LEDs consume orders of magnitude less electricity to produce similar lighting without appreciable waste heat.

The final justification for forcing builders to keep land free for future road-widening. This may sound like good urban planning, but it comes at such a high economic cost that may outweigh the benefits of future-proofing. This is because the land reserved for road-widening remains unproductive till the road is actually widened. Consider a hypothetical road 1 km long in Punjab (Ludhiana). The government mandates 3 m setbacks on both sides for future road widening. This results in 6,000 sqm (3 m X 1 km X 2 sides) of land left useless. Let us assume that the road is finally widened 20 years after the area was developed. For these 20 years, the land would not generate any economic activity. The rental yield for industrial land is roughly 10% per annum. This results in a loss of Rs. 2.6 crores in just rental income over this 20-year period. The total economic loss for this period will be significantly higher than this estimate, as rent does not capture the total economic return from using the land. Ludhiana has a road network of 1,356 km which would translate to Rs. 177 crores of rental yield loss per year with just 3 m of setback on each side of the roads. For perspective, this is ~15% of the city’s budget.

Setbacks across states seem to be set without an appropriate accounting of costs and benefits, and often display false scientism. India needs to be the next world-class manufacturing hub. For this, factories need to scale and expand horizontally. States must avoid deploying central planning through indirect means, where the government favours select industries through differing regulations that have no effect on safety. Revising setback norms may be a low-hanging fruit for reforms in building regulations. Rationalising setbacks may provide Indian industry with precious land to expand production, increase employment, and contribute to India’s prosperity.

References

Cicione, A., Walls, R., Sander, Z., Flores, N., Narayanan, V., Stevens, S., & Rush, D. (2021). The effect of separation distance between informal dwellings on fire spread rates based on experimental data and analytical equations. Fire technology, 57, 873-909.

Edwards, L., & Torcellini, P. (2002). Literature review of the effects of natural light on building occupants.

Horne, T. D. (1968). Zoning: Setback lines: A reappraisal. Wm. & Mary L. Rev., 10, 739.

Kumar, M. K., & Kranthi, N. (2017). Impact of Setbacks on Interior Daylighting in Residential Buildings: A Case Study of Vijayawada, India. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 10, 42.

Lee, J. A., Lee, J. H., & Je, M. H. (2021). Guidelines on Unused Open Spaces Between Buildings for Sustainable Urban Management. Sustainability, 13(23), 13482.

Li, D. H., Wong, S. L., Tsang, C. L., & Cheung, G. H. (2006). A study of the daylighting performance and energy use in heavily obstructed residential buildings via computer simulation techniques. Energy and buildings, 38(11), 1343-1348.

Patel, B., Byahut, S., & Bhatha, B. (2018). Building regulations are a barrier to affordable housing in Indian cities: the case of Ahmedabad. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 33, 175-195.

Bhavna Mundhra and Shubho Roy are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Sargun Kaur and Anandhakrishnan S for painstakingly mining and analysing the regulations.

Question: In a setting such as India, where dispute resolution systems are broken, and therefore incentives for commercial property developers / owners to protect consumers are low, are "set-backs" a way to reduce fire incidents (even if it is a less than ideal solution)? "Singapore’s freedom from setbacks does not seem to contribute to higher rates of industrial fire spreads" - the alternative view here could be that businesses in Singapore (with its legal systems, norms etc.) have enough incentives to protect its users, and therefore does not require prescriptive regulations such as set-backs? What's the right way to think about this?