#37: The wide road to nowhere

States may be losing out on industrialisation in 50% of rural areas due to minimum road width requirements

The 2024-25 Budget announced fast-tracking the growth of the rural economy as a key policy goal:

“Fast-tracking growth of the rural economy and generation of employment opportunities on a large scale will be the policy goal.”

In order to develop the rural economy, states will need to reconsider some critical regulations that prevent industries from being set up in the hinterland. Location and site related restrictions such as road width requirements are one such regulation. Building bye-laws typically allow construction only if plots abut roads with the prescribed width. This problem is particularly striking in the case of rural India, where industrial building is only allowed if the abutting road is of a minimum width, but less than a fifth of roads are actually of the prescribed width.

Minimum road width requirements aim to solve for tomorrow. These requirements are mandated to avoid any blockage of access on narrow rural roads. Any vehicle breakdown, particularly larger vehicles like trucks, could impede movement unless there was room for passage. Moreover, with the increase in economic activity, more vehicles would ply on these roads, creating congestion.

However, they fail to solve for today. Rural roads in large parts of India are narrow. For context, in 17 cities in India, 80% of roads are less than 8 m wide (Sholmo et al., 2016). Since there are very few roads in rural areas that meet the minimum width criteria, no industry can be found in these areas. These requirements in rural areas put an embargo on industrial development in the hinterland. Besides, the requirement to hand over land for future road widening increases the cost of setting up industries.

Using an example from one state, we show the cost of this embargo on industrialisation in rural India. We show how a data-based approach can help the state solve for today and for the future.

The problem

Road infrastructure planning is guided by different organisations, guidelines, and regulations in India. Indian Roads Congress (IRC) publishes guidelines, particularly on the geometric design and build of the road infrastructure in the country. The National Building Code of India and building regulations of different states utilise these guidelines to inform road width standards. Typically, states use the following definition of road width/right of way requirement:

“Any highway, street, lane, pathway, alley, stairway, passage way, carriage way, footway square, bridge, whether a thorough –fare or not, place on which the public have a right of passage, access or have passed and had access uninterruptedly for a specified period or whether existing or proposed in any scheme, and includes all bunds, channels, ditches, storm water drains, culverts, side walks, traffic islands, roadside trees and hedges, retaining walls, fences, barriers and railings within the street lines.”

(Part 3, National Building Code 2016, emphasis added)

Per the definition, a road width requirement can refer to the existing road width or the proposed width to which the road could be widened in the future. In cases where the road is proposed to be widened in the future, property buyers are required to cede part of their land as right-of-way.

States prescribe a minimum road width requirement depending on building type and location. The requirements for rural areas are much lower than for urban areas. For example, to set up a hotel in an urban area of Gujarat, the plot must abut a road at least 24 m wide. To set up an IT office in an urban area of Haryana, the plot must abut a road at least 15 m wide. To set up a light industry in a rural area of Telangana, the plot must abut a road at least 12 m wide. To set up a residential building in a rural area of Andhra Pradesh, the plot must abut a road at least 12 m wide. To set up a cottage industry in a rural area of Odisha, the plot must abut a road at least 9 m wide.

However, in light of the intention to fast-track the rural economy, the minimum road width requirements in rural areas may still be too restrictive. The most liberal requirement we have seen is 6.70 m, which could allow two heavy commercial vehicles to pass to and fro with some clearance room. In fact, most states have undertaken to expand rural roads to 18 m wide. These requirements are, as the data below will show, setting up an unrealistic expectation of current and future road use.

Case: Factories in Punjab’s rural areas

Punjab sets the most liberal minimum road width requirements in the country. A recent notification to improve industrialisation states:

“In order to boost industrial development in the state of Punjab, the standalone industries can be considered for approval subject to fulfilment of sitting guidelines on 4 Karam (6.70 m) rasta...”

(Government of Punjab notification dated 03-11-2021)

A village approximately 11 km away from Ludhiana—Punjab's textile manufacturing hub—provides an example of the effect of the minimum road width regulation. The state government is considering moving factory units away from the centre of Ludhiana to outlying areas. One outlying area that can host Ludhiana’s textile industry is the village of Ladian Kalan, located just 11 km from the city. The village is spread across 1.92 sq km and is serviced by a 14 km road network.

As the table above shows, 81% of the road length of Ladian Kalan does not meet the minimum road width requirement and cannot be industrialised.

These minimum road width regulations have an associated economic cost. A cost-benefit analysis can help policymakers make an informed decision. Consider three situations:

Situation 1: Today, where the government sets a minimum road width requirement of 6.70 m. At a 6.70 m limit, 81% of the road length of Ladian Kalan will not be available for industrialisation. Ladian Kalan will be able to generate at most 8,875 jobs in this situation.

Situation 2: Emergent order approach, where the government removes the minimum road width requirement altogether. The government will leave it up to the people to figure out the right of way, traffic congestion, repair of vehicle breakdowns, and adequate locations to set up factories. In this situation, conflicts pertaining to public goods will emerge, but Coasian bargains will also emerge (Coase, 1960). In this situation, 100% of the road length of Ladian Kalan will be available for industrialisation. Ladian Kalan could generate up to 44,462 jobs in this situation, 400% more than today.

Situation 3: A data-based approach, where the government sets road width requirements accounting for current realities. Today, 66% of roads in Ladian Kalan are ≥ 5m in width, 50% of the roads are ≥ 5.5 m in width, 32% are ≥ 6 m in width, and 19% are ≥ 6.70 m in width.

Indian Roads Congress guidelines for rural road development state that a standard carriageway should measure 3.75 m, and a two-lane road should measure 7.5 m wide including road shoulders and parapets (Indian Roads Congress, 2002). The 3.75 m carriageway can accommodate the widest vehicle (i.e., 2.6 m wide per the Central Motor Vehicles Rules 1989) along with side clearance. Typically, a heavy commercial vehicle is 2.6 m wide, a car is 1.7 m wide, and a two-wheeler is 0.6 m wide.

Based on this, a 5 m road would allow for passage of 1 heavy vehicle and a two-wheeler. A 5.5 - 6 m would allow for passage of 1 heavy vehicle and 1 car. No question that these movements will be constricted, but are feasible. Optimising for vehicle passage and job creation, a 5 m road may be a more reasonable choice than 6.7 m as today. This small change can allow for the creation of up to 29,342 jobs, 250% more than today. In fact, reducing the road width requirement by just 1 m can increase the jobs that can be created in Ladian Kalan by 140%.

Not the exception

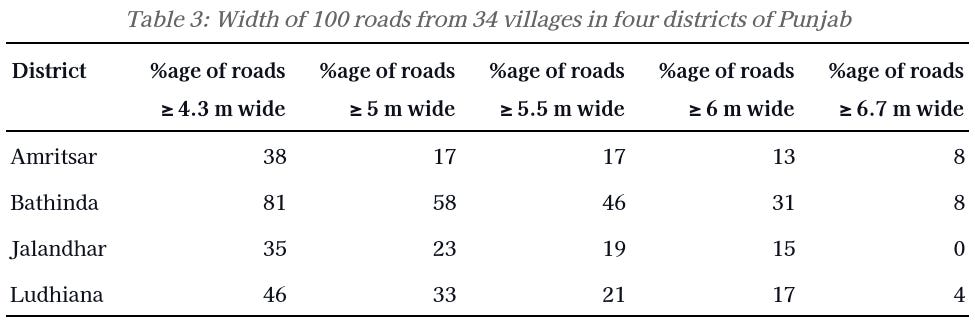

Minimum road width requirements act as a de facto embargo on all industrial development in rural areas. The illustration from Ladian Kalan is not the exception, but the rule. Most roads in rural Punjab are not amenable to industrialisation. A survey of 100 roads from 34 villages in four districts of Punjab (Amritsar, Bathinda, Jalandhar, and Ludhiana) shows that only 5% of the roads meet the minimum road width requirement for setting up industries. An average rural road in Punjab would need 2.2 m of widening before any industry can be set up. Table 3 below shows the results of the survey.

This situation is also not peculiar to Punjab; most states mandate minimum road width requirements of over 7 m in rural areas. Haryana, for instance, only allows the construction of small-scale industries in agricultural zones provided the minimum road width is 10.02 m. However, according to the Public Works Department of Haryana, 98% of village roads in 10 major districts of Haryana do not meet the minimum road width requirement

.Generally, there is a mismatch between the minimum road width requirement prescribed by states and the present reality of rural road infrastructure.

Choices for India

On the one hand, India aims to industrialise rapidly and the government provides a slew of incentives to enterprises. On the other hand, states mandate minimum road width requirements that cannot be met and therefore hamper industrialisation. Some states have started to recognise and address this problem. For example, Punjab rationalised the minimum road width requirement for factories in rural areas from 10.02 m to 6.70 m. The Government of Tamil Nadu has relaxed the minimum road width requirement twice for residential layout development in village areas, from 7.2 m to 7 m in 2020 and to 6 m in 2023.

Small changes like reducing road width requirements by 20% can unlock more than 50% of rural land for job creation, in turn enabling structural change of the rural economy and reducing pressure on urban areas. The 20% estimation is not unfounded: in most places, this will mean a reduction of minimum road width requirements to 5-6 m. The National Guidelines by Indian Roads Congress suggest that rural roads with low traffic volume can be 6 m wide (Indian Roads Congress, 2002). In fact, research suggests that rural roads with traffic volumes of 100 vehicles per day can also manage with a width of 5 m (Kadiyali, 2021).

No doubt, there is a future-looking problem to solve, that of widening roads as needed. This will require careful planning and consideration of the private costs incurred by land owners and developers. Today, some states propose a three-fold increase in road width in the future and demand that industries hand over land for future road widening free of cost. For instance, in Kakatiya, Telangana, all village roads are proposed to be widened to 18 m, and the landowner must compensate for any shortage in the existing road width. Dual restrictions on existing and proposed road width may lead to the exit of critical investment from the state. But, this is a topic for another day.

Conclusion

Minimum road width requirements are not the only regulation that leads to the loss of productive land. Other building regulations like ground coverage, setbacks, floor area ratio, and parking result in the loss of jobs and economic activity. The opportunity cost of the minimum road width requirement is the government losing out on resources, taxes, and employment generation opportunities. Therefore, such regulations should be enacted with great care and accompanied by appropriate economic analysis.

References

Anand, B., Kaur, S., & Anandhakrishnan S. (2023, September 6). Parking Reserved [Substack newsletter]. Prosperiti Insights.

Anand, B., Kaur, S., & Roy, S. (2023). State of Regulation: Building standards reforms for jobs and growth. Prosperiti.

Anandhakrishnan S, Anand, B., & Roy, S. (2023, June 28). Stunted Growth [Substack newsletter]. Prosperiti Insights.

AutoX. (n.d.). Hero Splendor Plus Dimensions, Length, Width and Height. autoX. Retrieved 29 October 2024, from

Bureau of Indian Standards. (2016). National Building Code of India Volume 1. Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution.

Coase, R. H. (1960). The Problem of Social Cost. The Journal of Law & Economics, 3, 1–44.

Department of Architecture and Regional Planning, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur. (2011). Final Proposal: Comprehensive Development Plan for Cuttack Development Plan Area (CDPA). Government of Odisha.

Directorate of town and country planning. (2021). Notification for amendment in Unified Zoning Regulations of Master Plans. Government of Punjab.

Directorate of Town and Country Planning. (2021). Notification to allow standalone industrial projects on 4 karam rastas (Notification no 6816-42 CTP CPBO/SP-432-Gen). Government of Punjab.

Glaeser, E. L., Kallal, H. D., Scheinkman, J. A., & Shleifer, A. (1992). Growth in Cities. Journal of Political Economy, 100(6), 1126–1152.

Government of Tamil Nadu. (2019). Tamil Nadu Combined Development and Building Rules (Rules G.O. (MS) No. 18). Government of Tamil Nadu.

Government of Tamil Nadu. (2020). Amendments to the Tamil Nadu Combined Development and Building Rules, 2019 (G.O. Ms.No.16, Municipal Administration and Water Supply (MA1) Department, 31st January 2020).

Hindustan Times. (2023, March 28). Units in mixed land use areas to get 5-yr extension: Ludhiana MLA Sidhu.

Ibiknle, D. (2023, August 23). Average Car Sizes: Length, Width, and Height. Neighbor Blog.

Indian Roads Congress. (2002). Indian Rural Road Congress Special Publication 20: Rural Roads Manual.

Kadiyali, L. R. (2021). Choice of low cost standards and specifications for rual roads. Ministry of Shipping and Transport (Roads Wings).

Kakatiya Urban Development Authority. (2018). Master Plan for Kakatiya (Warangal) Development Area 2041. Government of Telangana.

Kaur, S., & Roy, S. (2023, May 17). Losing Ground [Substack newsletter]. Prosperiti Insights.

Ministry of Finance. (2024). Budget 2024-25; Speech of Nirmala Sitharaman Minister of Finance. Government of India.

Mundhra, B., & Roy, S. (2023, May 31). At the Margin [Substack newsletter]. Prosperiti Insights.

Public Works Department (Building and Roads). (2022). Detail of Other District Roads, Haryana. Government of Haryana.

Roy, S., & Anand, B. (2024, June 19). Getting Economics into India’s laws [Substack newsletter]. Prosperiti Insights.

Sholmo, A., Lamson-Hall, P., Madrid, M., M. Blei, A., Parent, J., Sanchez, N. G., & Thom, K. (2016). Atlas of Urban Expansion: The 2016 Edition, Volume 2: Blocks and Roads. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

The New Indian Express. (2024, March 9). Tamil Nadu govt relaxes minimum road width norm for layouts in TN.

Town and Country Planning Department. (2021). Amendment in the Annexure-‘B’ of various Development Plans related to Zoning Regulations governing the change of land use with respect to industrial use in agriculture zone of all potential zones/towns-grant of Change of Land use permission for setting up of industries in agriculture zone (Memo No. Misc-452/2021/7/4/2021-2TCP). Government of Haryana. Retrieved 29 October 2024, from

Vahak Operations. (2024, February 19). Understanding Truck Sizes in India: A Complete Guide. Vahak.

Bhuvana Anand, Sargun Kaur, and Shubho Roy are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Bhavna Mundhra for collecting data on road widths in Punjab.