#24: Trends in Amendments to Building Regulations

In 3 states, 65% of amendments to building regulations increase the freedom to build

State governments in India frequently offer relaxations to building rules (See here, here, and here). These relaxations are usually seen as a positive move to ease construction and encourage economic development. However, these relaxations point to a deeper problem—states mandate standards that are often infeasible to comply with or to enforce, and subsequently have to grapple with lived reality. Wishful standards look good on paper, but, in a developing country, cost us jobs and income, not to mention precious administrative time.

In this article we show the trends in relaxations in building bye laws across three states. Through a hypothetical, we show the cost of having begun from a more restrictive position vis-a-vis the relaxed position. States could create more jobs and economic growth if they began with relaxed standards, instead of starting with strict standards and relaxing them over time.

Trends in amendments

This article analyses the amendments for three state building regulations: Haryana Building Code of 2017, Tamil Nadu Combined Development and Building Rules 2019, and Uttar Pradesh’s NOIDA Building Regulations 2010. The governments of Haryana, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh (Noida) amended their building regulations 18 times in the past decade—10 times in Haryana, two times in Tamil Nadu, and eight times in UP (Noida). These amendments brought about 215 changes for different buildings.

On average, 65% of the changes increase the freedom to build, either by liberalising building standards to unlock land and built-up area, or, by simplifying building approval procedures to reduce time, cost, and uncertainty.

Of the 215 changes, 75% relate to building standards, and 25% relate to the building approval procedure.

States have issued amendments for different types of buildings—commercial, industrial, residential etc. Of the total 215 changes, 45% apply to all types of buildings. The remaining 55% are changes instituted for one specific building type. Haryana issues the highest number of unique changes for industrial buildings, Tamil Nadu for residential, and Uttar Pradesh (Noida) for commercial buildings.

Most of the revisions across the three states concern the external features of buildings, like setbacks, parking, ground coverage, FAR, boundary walls, height restrictions, and open space reserves.

States are liberalising building standards to unlock productive land

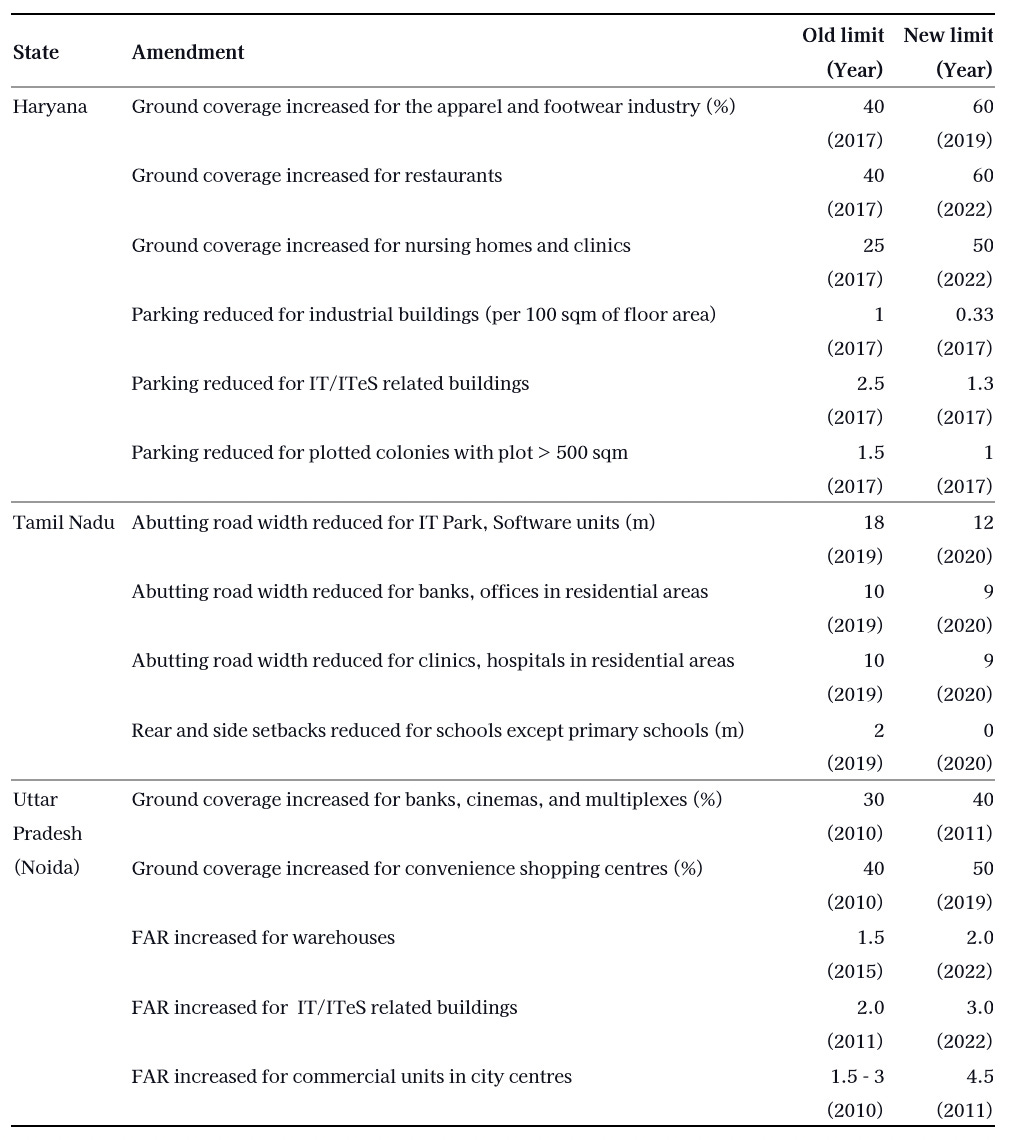

Buildings are constrained by standards that regulate the built form, density, and location. All three states issued amendments to institute more liberal standards that help unlock productive land, encourage vertical growth, and reduce restrictions on where a building can be constructed (Table 3).

States are also simplifying approval procedures to reduce time and cost

Building regulations outline procedural requirements to acquire construction permits. States have issued amendments that simplify the procedure and reduce the time or cost required to acquire different construction permits. For example, in 2020, just one year after notifying the Tamil Nadu Combined Development and Building Rules, the state exempted industrial buildings from paying the security deposit due under Rule 39. Presumably, the factory owners tabled dissatisfaction with locking up operational capital for long periods. Similarly, in Haryana, just eight months after notifying the Haryana Building Code, the state allowed all low-risk commercial buildings to self-certify their building plan approval applications, a previously unavailable facility. This self-certification allows the building owners to initiate construction right after submission instead of waiting for the authority's approval.

Policy Implications: A hypothetical from Haryana

The following illustration estimates the cost of stringent standards through a hypothetical. Haryana’s 2017 Building Code set a 40% ground coverage limit for apparel and footwear industries as opposed to 60% for general industries. Just 2 years later, in 2019, they amended the code to make it 60% for apparel and footwear industries.

What was the cost of restricting industries for two years? Consider a large apparel factory on a 10,000 sqm plot in Haryana. If constructed after the amendment, the hypothetical factory would have reduced the lost jobs and cost of land by 50% (Refer to Table 4). Factories constructed before 2019 will either keep paying the penalty for stringent standards or bear the cost of reconstruction to take advantage of relaxed standards.

The losses at the factory level add up to significant costs for the apparel industry in Haryana. Between 2017 and 2019, Haryana added 298 apparel and footwear factories. These factories added 25,026 jobs (21.7% growth) and Rs 2,842 crores (12.5%) to the state’s total output. If ground coverage were 60%, the same 298 factories could have added 37,539 jobs (32.5% growth) and Rs. 4,263 crores (13.4%) of economic activity.

The case of building regulations in India demonstrates that over-regulation comes at a cost that is difficult to mitigate by amendments alone. Indian building regulations set restrictive standards that hamper the freedom to build. States realise this over time and then course-correct by issuing frequent amendments to liberalise stringent requirements. While these amendments are welcome, it is important to recognise the consequences of overregulation in the first place. The time gap between over-regulation and liberalisation costs the economy jobs and resources.

Starting with over-regulation is unfair to first-movers, and may discourage them from entering the market. Buildings once constructed cannot be demolished or renovated easily to take advantage of the eased requirements. A restaurant owner in Haryana could have saved 20% of additional land by setting up the restaurant in 2022—five years after the original code was published. This might encourage investors to withhold investment expecting the government to course-correct eventually.

Way forward

How can governments avoid this pattern of starting with strict regulations and then proceeding with gradual relaxation? Three strategies may help state governments avoid the pitfalls and encourage jobs and economic growth:(i) avoid industrial planning through building regulations; (ii) make initial standards cognisant of Indian realities; and (iii) make regulations using cost-benefit analysis.

Building regulations in India often engage in industrial planning. Regulations prefer some industries over others by relaxing standards for one specific industry, even if the industry does not pose any special risk to the built environment. For example, two similar industries– carpet manufacturing and garment manufacturing– were treated differently in Haryana’s building regulations, despite no significant difference in the risks or externalities posed by these industries. Similarly, NOIDA’s (Uttar Pradesh) building regulations discriminate between shopping complexes and multiplex cinema halls, without any economic justification.

States may benefit themselves, their economy, and the working population by avoiding such industrial planning/preferences through building regulations. This would significantly simplify the already complex codes. Different criteria may be imposed only if the building poses unique risks or externalities. For example, petrol pumps pose higher fire risks than restaurants and may justify differing regulations. But there may be no reason to differentiate between shopping complexes and multiplexes. Such an approach does not require the state to predict which industries will be successful in any area. At the same time, this approach maximises the economic benefits to all parties (the state, businesses, and workers) as all industries can use land to the maximum extent.

In addition to avoiding industrial planning, recognising Indian realities may benefit the government and the economy. Aspiring for global best practices is usually a good approach to regulation-making generally. However, most regulations come at the cost of reducing economic activity. For the first world, a small reduction in economic activity may not be significant, but for India, this can mean the difference between poverty and middle income. Therefore, the regulations in India should consider the economic cost imposed and weigh them against the benefits of increased economic activity. In some areas, as we have argued before (here, here, and here), Indian standards exceed standards found even in developed economies. These standards may be imposing unacceptably high economic costs.

A well-developed tool may help states weigh the costs imposed by regulations against the benefits from the same regulations– cost-benefit analysis. This tool can be used for building standards, where the benefits may be increased safety and the costs are incurred in terms of reduced economic activity.

States in India start with building standards and then amend them to respond to emergent needs. This approach imposes costs on the state, the economy, and the people. Responding to the needs of industry and the people shows that the government cares about the citizens. However, getting the regulations right at the first attempt may provide even more benefits.

You can access the data here.

Bhuvana Anand, Sargun Kaur, and Shubho Roy are researchers at Prosperiti. The data collection and analysis for this article and the first draft of the article were prepared by Bhavna Mundhra, a former researcher at Prosperiti.