#48: Colonial Clocks

How inherited laws and lost sovereignty continue to chain India's factories

Working hours matter inordinately in how workers and firms can organise their lives and earnings. Research shows that flexible working hours increase the efficiency of labour contracts, enabling employers to schedule more hours during busy periods and give workers incentives to continue working. Flexible working hours raise worker earnings by enabling voluntary overtime during demand peaks (Hart & Ma, 2008). Temporary increases in working hours also help manufacturers compete in modern markets and are essential for growth (Daniel Vazquez-Bustelo & Lucia Avella, 2006; Wickens, 1974).

However, India’s working-hour regulations provide little freedom to employers and workers for organising production. India sets a hard cap of 48 hours per week every single week. When demand surges, firms cannot adjust these hours and must rely on overtime priced at a 2x premium (the highest in the world). As a forthcoming State of Regulation report will show, Indian factories can neither compete on pace nor on cost, making India an unattractive supplier in time-sensitive global value chains.

This article takes an economic history view and asks how India got here. It examines the evolution of working hour limits in colonial India and in the UK. Specifically, the analysis shows how British protectionism and the British Raj’s need to preserve order catalysed the first limits on working hours in India. Finally, we distil lessons from history on the choices India faces today as it seeks to become a manufacturing powerhouse.

How factory work was regulated

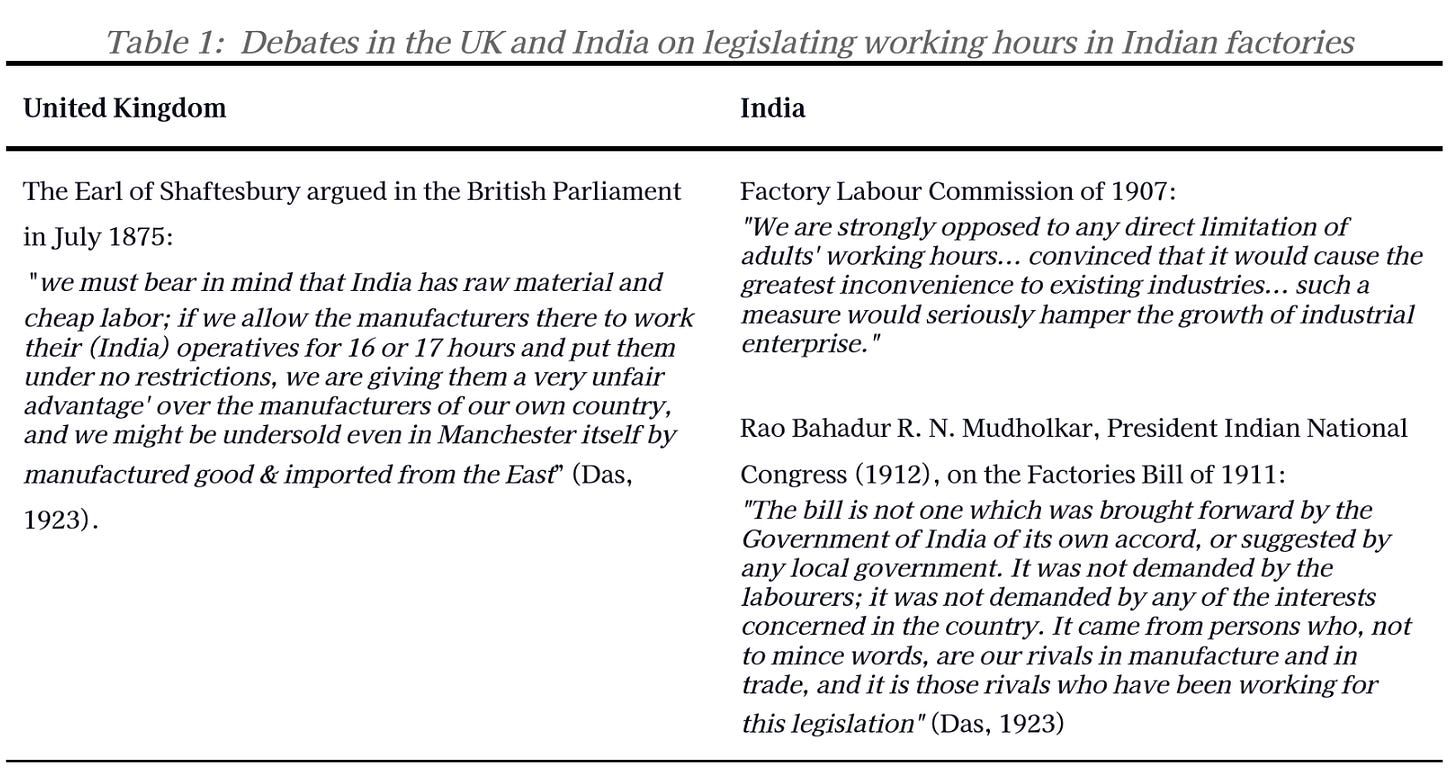

Working-hour limits in India were initially mooted by British cotton and jute industry manufacturers under threat from Indian competition. In the late 1800s, manufacturers in Manchester and Dundee began lobbying against Indian industry in the British Parliament, arguing that the continuous and unrestricted operation of mills gave Indian producers unfair advantages (Das, 1923; Tomlinson, 2015). From the time of the establishment of the first local mill in 1851, Indian cotton-spinning, weaving, and jute factories were growing rapidly. By the late 1870s, there were at least 80 factories in Bombay and Calcutta, employing upwards of 60,000 workers daily (Das, 1923; Kydd, 1920).

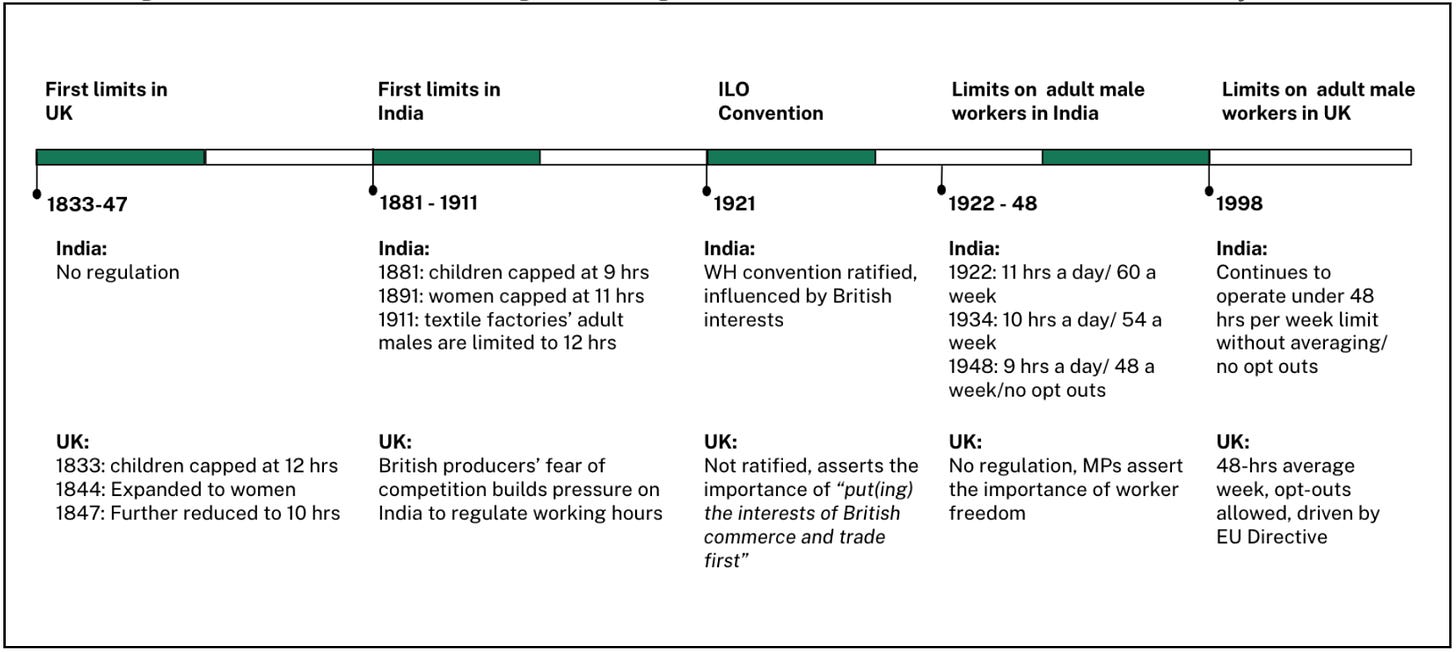

Indian mills enjoyed a competitive advantage; while children and women in the UK were not allowed to work more than 12 hours a day, no such restriction applied in India.1 The colonial government, at the behest of the Manchester Chamber of Commerce and over the protests of Indian nationalists, introduced the first limits on working hours in India, for children in 1881, and subsequently for women in 1891 (Das, 1923; Gilbert, 1982). The same special interests were able to precipitate working-hour limits for adult males in Indian textile factories in 1911, 60 years ahead of similar legislation in the UK (Das, 1923).

The same colonial government bound India to international standards in 1921, and India became a founding member of the International Labour Organisation (ILO). The backdrop to this is the end of the First World War and the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, when the ILO is established. Gidney (2023) notes that India’s representation is “not carried out by elected Indian officials, but an amalgamation of Indian ‘loyalists’ led by British bureaucrats”, and separately shows the conceptualisation of the ILO as both born of an intent to modernise global labour standards but also to dull “the dumping of goods produced abroad under sweated conditions”.2

The British government took the lead in designing the new international labour regime as it reasoned that,

“from the British economic point of view, it was clearly to the advantage of a country that was among the most advanced in the regulation of conditions of employment to encourage the movement to that end. Once free competition had been restored it would be very difficult to raise the general standard of wages or condition or even to maintain the present minimum in industries which depended on foreign markets, unless similar standards were applied in all competing markets” (Alcock, 1971).

As a member of the ILO, India was required to demonstrate compliance and place the ILO’s Hours of Work Convention, 1919 (C001) before its legislature. India, influenced by international obligation, ratified the convention and in 1922 introduced an 11-hour-per-day, 60-hour-per-week limit, applicable to all workers regardless of gender. Britain itself never ratified the ILO Working Hours Convention. Instead, it chose to preserve its freedom to legislate in accordance with its economic needs.

Over the next twenty years, a series of committees instituted by the Colonial government reduced the working hour limits steadily, leading us to our current limits. The first reduction was a response to industrial strife in the late 1920s.3 A note from the Viceroy’s Department of Industries and Labour in 1928 shared concerns about both “extremist and communistic elements” and argued for further labour legislation as the “best antidote to communism” (Panesar et al., 2017). The consequent Whitley Commission (1929) proposed a further reduction in working-hour limits to 10 hours per day and 54 hours per week, which were then adopted in 1934. The next reduction came a decade later from the Labour Investigation Committee, set up as a result of the Tripartite Labour Conference, itself a product of the Whitley Commission. Two out of four reasons given by the Committee argued that a reduction in working hours to 48 hours a week would, in fact, increase employment (International Labour Organisation, 1949). Soon after independence, India implemented these recommended reductions.

In 1948, the country enacted a 48-hour weekly limit on the belief that the new limits would increase production in textile industries and act as a job-creation mechanism during the post-WWII transition (International Labour Organisation, 1949). These reductions were as the ILO itself observed “well in advance of” the exemptions India had secured to make development-appropriate regulations.4 Nowhere in the debates is the cost of regulation argument acknowledged.

A lesson in three contrasts

We often say India’s laws are colonial; the history of working-hours regulations in India and the UK offers an interesting contrast. Legislation that our colonial masters did not accept for themselves is a fascinating story of choice and circumstance. Understanding the route our erstwhile masters took offers an interesting perspective on economic reasoning, individual bargaining, and sovereignty. Quotes from the legislature in both countries are instructive of the evolution of working-hour regulations.

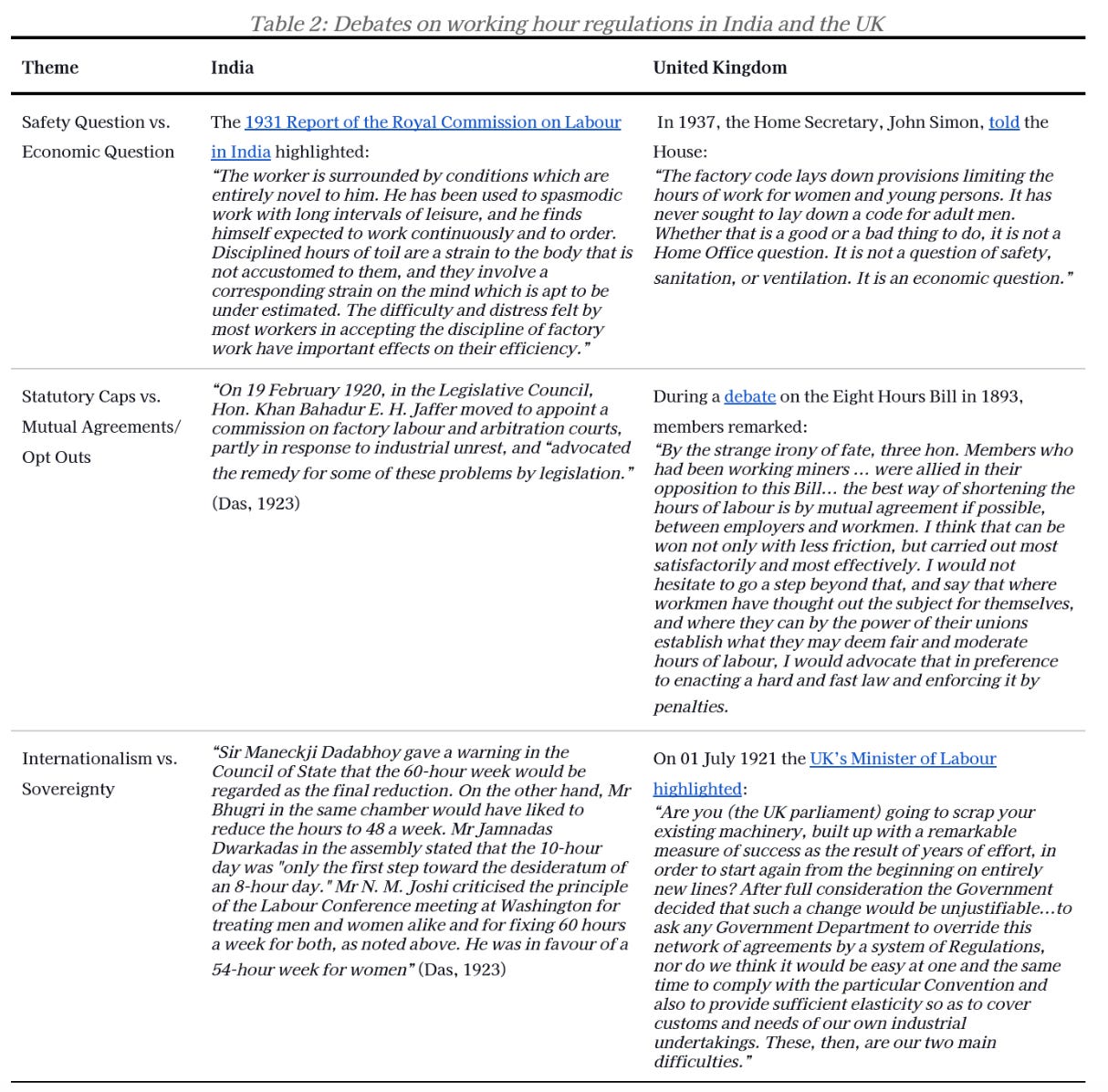

First, the UK kept adult men outside the factory law because legislators treated their hours as an economic question. When Britain introduced the Factories Act of 1833, there were concerns that broadening the scope of the Factory Acts to adult male workers could negatively affect industrial profits and that this should be avoided (Davies & Rodgers, 2023).

In contrast, Indian lawmakers have primarily viewed working hours as a health and safety concern and ignored the economic question. The Labour Investigation Committee, in its 1946 report, highlighted that ‘a forty-eight-hour week would provide immediate relief to workers in India’s factories who had worked under great strain during the Second World War’ (International Labour Organisation, 1949). Over the years, India’s lens has completely undermined an employer’s ability to organise their production flexibly and a worker’s ability to earn more, even if they want to. The lack of flexibility prevents Indian factories from increasing production to meet any surge in demand.

Second, the UK’s working hour regulations then, and now, emphasised individual worker autonomy, allowing workers and employers to negotiate arrangements. When the UK introduced the Factory Act in 1833, freedom to negotiate was an important concern. It was believed that extending the law would undermine the ability of adult workers to negotiate labour contracts in their own best interests (Davies & Rodgers, 2023). UK unions also preferred to secure hours through workplace agreements and opposed national caps on adult men (Wolcott, 2008). Finally, even after the UK introduced hour limits, workers were permitted to opt out. In fact, recent evidence shows that in 32% of UK firms, at least one employee has opted out of the limits, and in 15% of firms, all employees have opted out (Department for Business, Innovation & Skills, UK, 2014).

In contrast, Indian workers cannot opt out of the 48-hour limit. For legislators in India, enshrining hour limits in statute offered a means to avoid costly disruptions through strikes. Before India formally introduced legislation on working hours for adult men in 1922, factory owners had already voluntarily reduced these hours, without any legal requirement. The Buckingham and Carnatic Mills in Madras implemented a 10-hour day in 1919–20, following a series of strikes by workers that disrupted industrial activity across many parts of India. It also became the norm at factories in Dhariwal, Nagpur, and other locations (Das, 1923). Today, under the IR Code 2020, even the conditions of employment must be defined in consultation with worker representatives, including the shifts to be worked. Workers cannot withdraw from the agreement, even if they wish to.

Third, Britain prioritised sovereignty over rigid international standards. Britain’s Home Secretary during the House of Commons debate in 1925 on the International Labour Convention asserted that “we must put the interests of British commerce and trade first”. The UK extended working-hour limits for adult male workers only in 1998 under duress from the EU’s directives.5 Today, although the UK’s laws appear to mirror the ILO’s Working Hours Convention, it has never ratified the convention. The UK still has the option to change its mind without being penalised or held hostage by any international body.

In contrast, British India’s ratification of the Working Hour Convention continues to constrain our ability to relax working-hour limits. Early ratification locked us in rigidity long before we became an industrial power. In fact, of the 47 countries that enforce the ILO convention on working hours today, only India, Pakistan, Myanmar, and New Zealand ratified it prior to independence. Of these, New Zealand officially denounced the ILO conventions on hour limits on June 9, 1989, stating: “...no longer reflect the methods of work in force in New Zealand and are regarded as a brake on the adoption of more flexible working hours.” The pursuit of internationalism has come at the expense of binding India in a severe and unyielding commitment.

Conclusion

India first regulated working hours 60 years after the UK, but hardcoded them 60 years before. The UK took a very pro-worker-freedom approach. They introduced safety limits for children and women 20 years earlier than we did, but we universalised them much earlier. They treated working time as an economic variable; we treated it as a uniform welfare entitlement. They trusted individual bargaining and workplace agreements; we set inflexible statutory limits. They allowed opt-outs; we insisted on no exceptions. They debated which international rules best fit context and only adopted limits under external pressure; we accepted global standards and internalised them as permanent, universal constraints.

Working hours were presented to us as a form of protection, when in reality they were protectionist. The limits were imposed on us, but we also chose to continue to adhere and make them more severe. Clinging to rigid, universal hour limits, rooted in colonial protectionism, continues to constrain India’s economic dynamism. These colonial-era regulations distort employment decisions, suppress flexibility, and blunt the ability to compete. Dismantling this inherited rigidity is no longer a question of historical correction but an urgent economic imperative.

References

Alcock, A. E. (1971). History of the International Labor Organization. Internet Archive; Octagon Books.

Blair, A., Karsten, L., & Leopold, J. (2001). Britain and the Working Time Regulations. Sage Journals.

Chandra, B. (2010). The Rise and Growth of Economic Nationalism in India: Economic Policies of Indian National Leadership, 1880-1905. Har Anand Publications.

Das, R. K. (1923). Factory legislation in India. Walter De Gruyter & Co.

Davies, A., & Rodgers, L. (2023). Towards a More Effective Health and Safety Regime for UK Workplaces Post COVID-19. Industrial Law Journal, 52(3), 665–695.

Department for Business, Innovation & Skills, UK. (2014, December 24). Working Time Regulations: Impact on UK labour market. GOV.UK.

Gidney, T. (2023). The Development Dichotomy: Colonial India’s Accession to the ILO’s Governing Body (1919–22). Journal of Global History, 18(2), 259–280.

Gilbert, M. J. (1982). Lord Lansdowne and the Indian Factory Act of 1891: A Study in Indian Economic Nationalism and Proconsular Power. The Journal of Developing Areas, 16(3), 357–372.

Hart, R. A., & Ma, Y. (2008). Wage–hours contracts, overtime working and premium pay. Labour Economics, 17(1), 170–179.

International Labour Organisation. (1949). A decade of labour legislation in India: 1937-1948. I. International Labour Review, 59(4), 394–424.

Kydd, J. C. (1920). A History of Factory Legislation in India. Calcutta University Press.

Panesar, A., Stoddart, A., Turner, J., Ward, P., & Wells, S. (2017). J.H. Whitley and the Royal Commission on Labour in India 1929–31. In Liberal Reform and Industrial Relations: J.H. Whitley (1866-1935), Halifax Radical and Speaker of the House of Commons. Routledge.

Tomlinson, J. (2015). Orientalism at Work? Dundee’s Response to Competition from Calcutta, circa 1870–1914. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 43(5), 807–830.

Vazquez-Bustelo, D., & Avella, L. (2006). Agile manufacturing: Industrial case studies in Spain. Technovation, 26(10), 1147–1161.

Wickens, M. R. (1974). Towards a Theory of the Labour Market. Economica, 41(163), 278–294.

Wolcott, S. (2008). Strikes in Colonial India, 1921–1938. ILR Review, 61(4), 460–484.

Working-hour restrictions began in 1819 in the UK, where children aged 9 to 16 were limited to 12 hours of work a day. In 1844, the UK extended restrictions to women with a daily limit of 12 hours.

For instance, India’s dissent against the composition of the Governing Body was not directed by a delegation from an independent state but as a British colony attempting to secure another seat for the British Empire on the Governing Body (Gidney, 2023).

During the interwar period between the First and Second World Wars, the Bombay Presidency lost 23 days per year to strikes, compared with less than 3 days in England and in the US (Wolcott, 2008).

At the 1919 Washington International Labour Conference, Indian delegates successfully secured an exemption under Article 405(3) of the Treaty of Versailles, allowing a 60-hour workweek. This exemption recognised that “the imperfect development of industrial organisation” in countries like India made their “industrial conditions substantially different”, necessitating special consideration in framing labour recommendations. The ILO in its International Labour Review 1949 noted that “...the existing practice in India with regard to hours of work in factories is well in advance of the special provisions concerning India laid down in the international labour Convention No. 1, concerning hours of work in industrial undertakings.”

Following the establishment of the EU, the UK was obligated to adopt the 1993 EU Working Time Directive. The UK government initially challenged the directive in the European Court of Justice, arguing that working hours were a domestic issue to be negotiated among employers, trade unions, and employees. This position was driven by a desire to maintain a competitive edge within the EU (Blair et al., 2001). The European Court of Justice rejected this challenge on 12 November 1996, compelling the UK to implement regulations.

Arjun Krishnan, Bhuvana Anand, and Pranjal Chandra are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Abhishek Singh for his help in understanding legal history and brainstorming arguments.

Thank you, neural foundry. New Zealand deep dive coming soon!

Absolutely brilliant historical analysis. The irony that British manufacturers lobbied for hour limits on Indian factories 60 years before the UK accepted them domestically really underscores how protectionism gets dressed up as worker welfare. I've actualy seen similar patterns in trade policy where developing economies get locked into standards way too early. The fact that New Zealand bailed from these ILO conventions in '89 while India still cant flex shows how sovereignty matters more than people think.