#41: The ILO Shibboleth

India’s working hour limits are not faithful to the labour organisation’s recommendations

Indian states have faced opposition to attempts at amending working hour limits for factory workers. The Government of Karnataka amended working hour limits in 2023 to allow longer factory shifts. Two months later, the Government of Tamil Nadu unsuccessfully attempted amendments to working hour limits. Both states faced criticism for “setting the clock back” on labour rights and “pushing workers back to colonial times”, “acceding to the demands of industrialists” and enabling worker exploitation. In their attempts at reform, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu governments were also accused of violating ILO conventions.

Such opposition stems from an incorrect understanding of Indian law, ILO conventions, and global norms for regulating working hours. India regulates working hours for factory workers far more strictly than ILO requires. Even in Karnataka that recently reformed its regulations, factory workers have less freedom to decide their working hours than ILO conventions would allow. In contrast, other countries have rejected the ILO convention and have given their workers greater freedom in setting working hour arrangements.

In this article, we compare working hour limits in India with ILO conventions and regulations in other countries. We also examine the extent to which countries have accepted ILO conventions as the standard for their working hour regulations.

Indian limits on working hours are more restrictive than ILO conventions

India regulates working hours for factory workers more strictly than ILO conventions require. The Indian Parliament passed the Factories Act in 1948 to limit working hours for factory workers. Under the Act, factory workers must not work more than 9 hours a day or 48 hours a week.1 Factory workers cannot exceed these limits on any day or week, nor can they cannot negotiate with employers for longer hours. Under ILO conventions, factory workers must limit their work to 8 hours daily and 48 hours weekly. However, factory workers can exceed these limits on some days or weeks as long as they comply with the limits on average. Factory workers can also enter into agreements with employers for longer hours.

The following table compares working hour limits on Indian factory workers with ILO-recommended working hour limits.

First, India allows factory workers less flexibility than ILO conventions in deciding their daily and weekly hours. While ILO’s daily limits are lower than India’s limits, ILO conventions allow factory workers to average this over three weeks; i.e. they can exceed limits on daily and weekly hours as long as they reduce their hours in other weeks to meet the average.

Second, India prohibits factory workers from entering into agreements with employers for longer working hours. Under ILO conventions, factory workers can consent to 9-hour workdays in exchange for one 7-hour workday each week, a facility not available to factory workers in India. Under such agreements, factory workers can consent to work up to 52 hours weekly, four more than allowed in India.

Following ILO conventions would likely increase worker and enterprise freedom compared to the status today.

Amended limits in Karnataka are stricter than ILO conventions require

Karnataka has amended working hour limits to allow longer shifts in factories. These amendments do not violate ILO conventions. Karnataka allows workers in certain industries to work up to 12 hours a day as long as they limit weekly hours to 48. In effect, Karnataka allows workers to meet the ILO-recommended 8-hour limit on average across a week. Workers may choose to work for four, five or six days, adjusting their daily hours accordingly to meet the 8-hour limit on average. The following table shows the working hour arrangements that workers in Karnataka can choose in practice.

Even with these reforms, Karnataka‘s working hour regulations are more restrictive than ILO conventions. In Karnataka, the flexibility to adjust daily working hours on average across a week is only available to workers in specially exempted sectors. Under ILO conventions, factory workers in all sectors can adjust their daily and weekly working hours to meet working hour limits on average across three weeks. Table 3 compares the working hour limits set by Karnataka and ILO.

Indian workers have lesser freedom in deciding their working hours than allowed under ILO norms. In contrast, workers in other countries have more freedom to decide their working hours than ILO allows.

Other countries allow more freedom in deciding working hours than ILO

Other countries allow factory workers greater flexibility in deciding their working hours than ILO. In other countries, factory workers have the freedom to meet working hour limits on average across periods ranging from 3 to 52 weeks. Countries like Germany recognise flexibility in working hours as an important objective for the law regulating workers.

“ The purpose of the Act is:

to ensure the safety and protection of the health of the employees in the establishment of work shifts and to improve the general conditions for creating flexible work shifts, …“

(§ 1, Working Time Act, 1994, Germany)

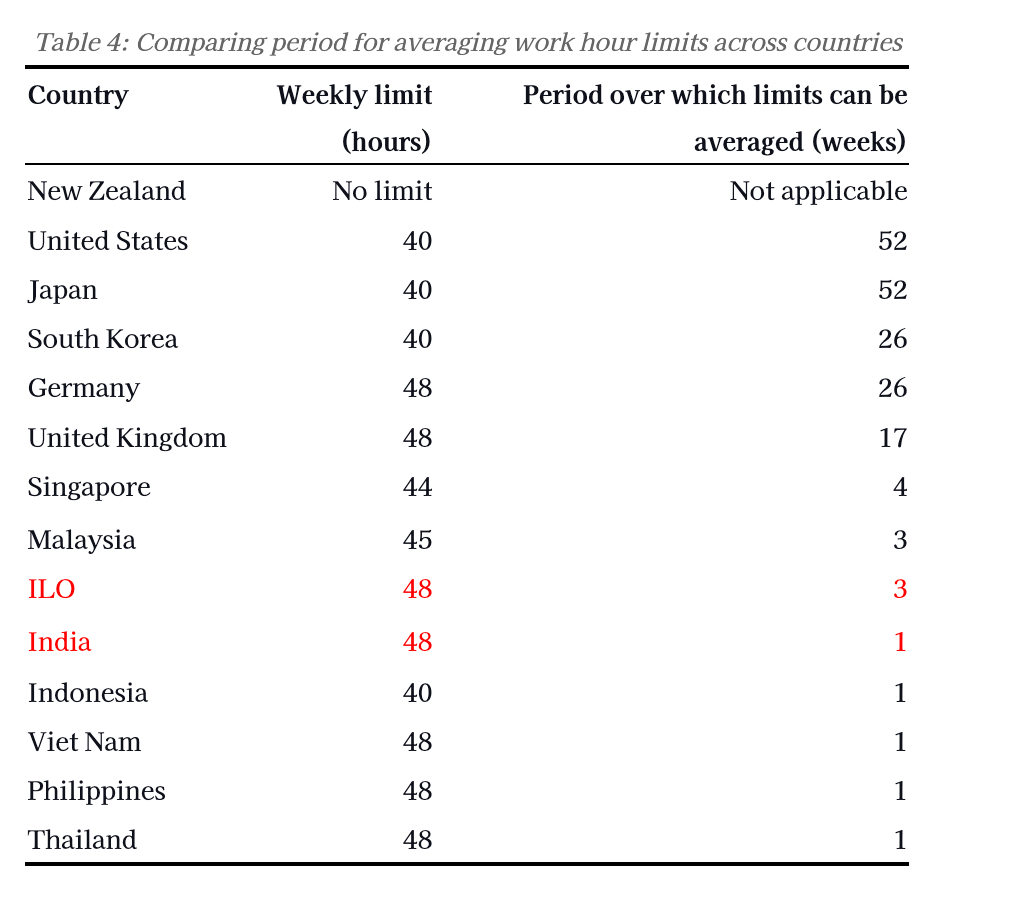

Table 4 compares weekly working hour limits and the maximum permissible period to meet working hour limits on average for ILO and 12 East Asian and European countries.

Many of the countries in the table above give workers greater freedom in choosing working hours than is permissible under ILO conventions. To allow these freedoms, other countries have rejected the ILO convention on working hours.

ILO limits are not the globally accepted norm on regulating working hours

Other countries do not consider ILO conventions to be the globally accepted norm on working hours. ILO conventions on working hours are ratified by fewer countries than other ILO conventions affecting factory workers. Table 5 compares the number of countries that have ratified ILO conventions affecting factory workers, including the convention on working hours.

Other countries have rejected the ILO convention on working hours despite their general interest in protecting workers. Table 6 compares India with the same 12 East Asian and European countries based on the number of ILO conventions each country has ratified. Of the 12 countries, seven have ratified a comparable or higher number of ILO conventions than India. None of these countries except India has ratified the ILO convention on working hours. All 12 countries also have a higher per-capita income today than India.

Conclusion

At the very least, Union and state governments can allow factory workers greater freedom in deciding their working hours without violating ILO conventions. A simple modification of allowing averaging would allow factory workers to apportion their working hours more flexibly. Indian workers are forced to work the same number of hours throughout the year, with no room for variation. However, Indian workers can earn more if they are allowed to increase their working hours when presented with remunerative opportunities. For example, Indian workers can earn more by temporarily increasing their working hours to service an order of iPhones shortly before product launches. Without this freedom, Indian workers cannot maximise the revenue generated from their labour, which limits their income. This needn’t be the case since India has not yet instituted averaging, like the ILO recommends, and that other countries have adopted.

But, to be truly transformative for workers and firms alike, India must revisit its work hour limits as other countries have. Many Indian workers now engage in production for global markets. Therefore, Indian workers compete with workers from other countries for production opportunities and the attendant revenue. Unlike Indian workers, workers in other countries can dedicate the greatest proportion of their work hours to the most promising market opportunities. Indian workers should have a similar right to choose the opportunities that best compensate for their efforts. Contrary to popular criticisms, flexible work hours should be considered a right for all Indian workers.

References

Ahluwalia, R., Hasan, R., Kapoor, M., & Panagariya, A. (2018). The Impact of Labor Regulations on Jobs and Wages in India: Evidence from a Natural Experiment. Working Paper No. 2018-02.

Artuc, E., Lopez-Acevedo, G., Robertson, R., & Samaan, D. (2019). Exports to Jobs: Boosting the Gains from Trade in South Asia. World Bank.

Dougherty, S., Frisancho, V., & Krishna, K. (2014). State-level Labor Reform and Firm-level Productivity in India. India Policy Forum, 10(1), 1–56.

Greenwood, J., & Vandenbroucke, G. (2005). Hours Worked: Long-Run Trends. Working Paper 11629

Huberman, M., & Minns, C. (2007). The times they are not changin’: Days and hours of work in Old and New Worlds, 1870–2000. Explorations in Economic History, 44(4), 538–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2007.03.002

McLean, I. W. (2007). Why was Australia so rich? Explorations in Economic History, 44(4), 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2006.11.003

Mokyr, J. (2000). The industrial revolution and the Netherlands: Why did it not happen?De Economist, 148(4), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004134217178

Both these limits regulate the standard hours of employment for factory workers. Factory workers in India may avail more hours of work if the employer pays double the regular wage for each extra hour worked.

Abhishek Singh, Shubho Roy and Bhuvana Anand are researchers at Prosperiti.