#16: UnSkilling India

Laws designed to regulate apprenticeships are costing Indian youth the opportunity to upskill themselves

The percentage of the Indian population engaged in formal apprenticeship is 0.01%. In Australia, the same number is 1%, and the percentage of Germans engaged in formal apprenticeships is 2.7. The Indian government has made repeated efforts to boost apprenticeships. To this effect, the government started the National Apprentice Promotion Scheme (NAPS) in 2016. For this scheme, the government allocated Rs 220 cr in the 2022 budget (revised from Rs 170 cr). Despite the government’s efforts, the number of apprentices is low. The government had targeted to train 50 lakh apprentices by 2019-20, but by August 2023, only ~20 lakh (40%) apprentices had been trained. 50% of India’s population is under the age of 25, and the government is spending money to train them, yet India has one of the lowest percentages of apprentices.

Why is India’s apprentice population so low? One reason is probably India’s Apprentices Act 1961, which governs the hiring and training of apprentices. The law is supposed to regulate the training of apprentices, but the provisions of the law seem to be designed for the employing of apprentices. The law imposes several requirements on employers who take on apprentices, so much so that employers are discouraged from hiring apprentices in the first place. As a result, India’s youth cannot skill themselves to prosperity.

Stipend

The Apprentices Act harms apprenticeship by forcing employers to pay apprentices fixed stipends set down in the law. This stipend has no relation to the apprentice's actual productivity. An apprentice is, by definition, a novice with low skill. The apprentice may not generate enough revenue to justify the stipend fixed by law. In such a situation, the employer would incur a loss by appointing apprentices.

In other fields, the law recognises that the apprentice may not generate enough revenue to justify a high stipend. This recognition is seen in the difference between apprentices under the Apprentices Act and a high-skill profession like chartered accountants. Under the Apprentices Act, an apprentice must be paid at least Rs. 5,000 a month, even if the apprentice has had no training in the job they are being hired for. In contrast, a student of chartered accounting is entitled to only Rs. 2,000 (40% of apprenticeship stipend) per month in the first year of articleship (Regulation 48(1) of CA Regulation 1988). This amount is payable only after the prospective accountant has cleared accounting examinations. In other fields like medicine and law, the law does not mandate a minimum payment. The minimum pay difference between the Apprentices Act and other professional regulations highlights the conflict between training and employing. For the professions, the law recognises that the training is important and does not mandate payment from employers. In contrast, the Apprentices Act forces employers to pay a relatively high stipend.

In addition to fixing stipends, the law also harms apprenticeship opportunities by disconnecting apprenticeship pay from productivity. Instead, the law specifies pay to the apprentice based on the education of the apprentice, even if such education does not contribute to the productivity of the apprentice. Under the law, employers must pay apprentices higher wages, if they are more educated. The Act states that employers must pay Rs. 5,000 to apprentices who have studied till the 5th standard, but the same apprenticeship must be paid Rs. 9,000 (44% more) if the apprentice is a graduate. This is irrespective of the requirements of the job. For example, a tailoring job may be done equally well, irrespective of formal education. However, the law binds the hands of the employer. In such a situation, the employer may actively discriminate against better-educated applicants. Students who stay back in school may end up losing the opportunity to enter trades because the law prices them out of the market.

The central government seems to be aware of this problem of the law setting high stipends for apprentices. Consequently, the NAPS scheme subsidises stipends by providing 25% stipend, up to a maximum of Rs.1,500 per month, per apprentice during the training period. A better solution may be to allow employers and apprentices to negotiate acceptable pay.

The third way the Apprentices Act harms apprentices is by prohibiting piece-rate pay. Under the law (S. 30(2)(e)), the employer cannot pay apprentices by piece rate. Even though such a payment system is allowed (and quite common) for regular employees. As a result, employers may shy away from appointing apprentices in areas where skill and experience are directly linked to productivity. A 2014 paper found that apprentices (in mechanics and metalworking industries) are not even 20% as productive as skilled workers. However, the Apprentices Act forces employers to pay a fixed salary, irrespective of their productivity.

Education

On the one hand, the Apprentices Act discourages employers from hiring apprentices by fixing pay without considering productivity. On the other hand, the law discourages potential apprentices by banning them from pursuing education during an apprenticeship. Madras High Court has held that an Indian student undergoing any educational course cannot train as a part-time apprentice (B.Abraham Anand vs The Board Of Apprenticeship, 2017). This restriction creates anomalous situations which may force young people to drop out of formal education. Under the law, an apprentice is entitled to Rs. 5,000 a month if she has studied up to the 5th standard. However, to get this money, the student has to drop out of school because the law states that a person cannot be an apprentice and a student at the same time.

In contrast, the law poses no such restrictions on professional qualifications. Doctors, accountants, and lawyers are not only encouraged to undergo training during their education but the law makes it mandatory in the cases of doctors and accountants.

Other countries recognise and encourage apprenticeship by allowing simultaneous education and practical training. In Germany and Switzerland, apprentices split the work week between school and working with their employer. Up to two days may be spent at the vocational school and the rest of the week is spent with the host company implementing the learning. Nearly 70% of Swiss and 51% of Germans, between the ages of 15 to 22, have completed apprenticeship in this manner.

Indian law further discourages apprenticeship by turning the German model on its head. Instead of vocational schools (usually funded by the government), the employer must bear the burden of theoretical training (S. 9(8)(a)). This further discourages employers, who have to take up the additional burden of imparting theoretical training just because they took up the mantle of training apprentices.

Infrastructure

In addition to pay and education, the law harms apprenticeship opportunities by imposing infrastructure costs on employers. An employer with 500 workers is legally mandated to establish a separate building/section of the workshop building for imparting practical training (Schedule V of the Apprentices Rules 1992). This building is mandatory even if there are just 13 apprentices in the company. The cost of a new building may discourage employers who have to face all the other requirements of the Apprentices Act.

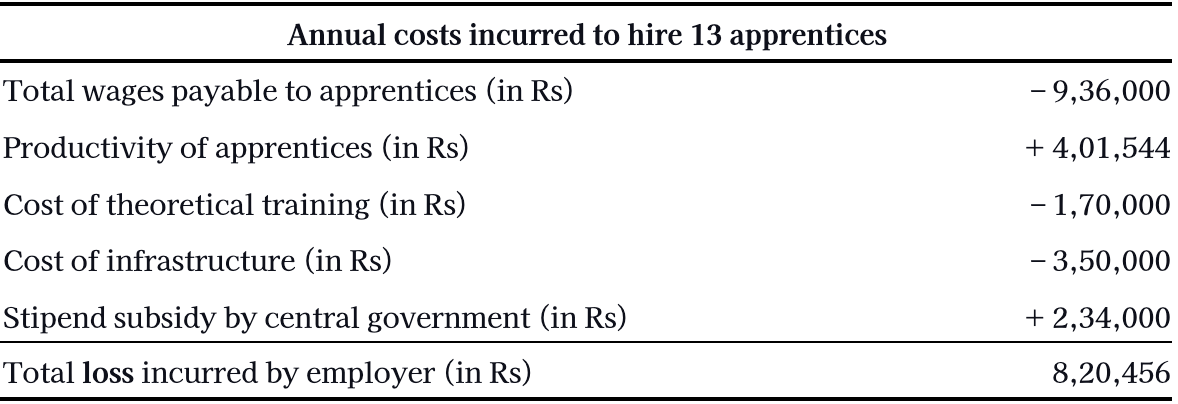

How much do employers stand to lose if they were to comply with India’s Apprentices Act? Let us take the example of a 500-worker metal factory in Surat, Gujarat. The employer of such a factory must legally hire 13 apprentices and provide them with theoretical training, a separate section/building for training, and a monthly stipend. Let us assume that apprentices are 20% as productive as skilled workers (Muehlemann & Wolter, 2014). As a result, the employer incurs a loss on wages exceeding 20% of a skilled worker’s wages. In Surat, the annual minimum wage of a skilled metal worker is Rs 1,54,440. The apprentice should be paid Rs 30,888 (20% of a skilled worker’s wages). However, the law forces the employer to pay an apprentice Rs 72,000 (47% of a skilled worker’s wages). The following table shows how much the hypothetical metal factory will lose in complying with the Apprentices Act.

As the table above shows, the government’s subsidy scheme does not offset the cost incurred by our hypothetical factory. Rational employers would attempt to avoid hiring apprentices, even if they would be profitable to the employer and the apprentice in the long term.

Termination

Even when apprenticeships have to be terminated, the law discourages employers from appointing apprentices. This is because the law requires employers to pay a minimum of three months severance for apprenticeships, which may last only a year (Rule 8 of Apprentices Rules 1992). In contrast, regular employees are usually entitled to one month's pay as severance (Section 30(2) of the Delhi Shops and Establishments Act, 1954; Section 25F Industrial Disputes Act, 1947). The law protects apprentices 3x more than workers. The following table compares the cost of firing an apprentice versus a regular employee in a garment factory in Ludhiana.

This illustration is probably an underestimate because an employer can make the employee work during the notice period, but the apprentice is not obliged to work during the three-month period for which she is being paid.

Conclusion

India has an apprenticeship problem. Of the 1,41,473 establishments registered on the apprenticeship website run by the government, only 25,832 establishments engage apprentices. The subsidy provided to employers by the government paying part of the stipend also has not helped.

India needs to produce skilled workers who can help achieve prosperity for themselves and their country. Apprenticeships are a time-tested method of skilling, but the Apprentices Act has hurt this effort. No amount of financial allocation or better implementation will improve the results of an ill-considered law. The Apprentices Act is emblematic of many Indian employment laws. The laws put so many burdens on employers that employment/training is discouraged in the first place. Reducing overspecifications and high standards within the law can allow firms to be at the forefront of skilling India.

References

Muehlemann, S., & Wolter, S. C. (2014). Return on investment of apprenticeship systems for enterprises: Evidence from cost-benefit analyses. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 3(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9004-3-25

B.Abraham Anand vs The Board Of Apprenticeship, W.P.No.9780 of 2014 And M.P.No.1 of 2014 (Madras High Court 10 October 2017).

Bhuvana Anand, Abhishree Choudhary, and Shubho Roy are researchers at Prosperiti.

Do these laws also create hurdles for white-collar apprenticeships?