#44: Peripheral blindness

How a law prevented five towns surrounding Chandigarh from developing for 50 years

Chandigarh has been celebrated as a model of modern urban planning in India. Conceived in 1952 to replace Lahore as Punjab’s capital post-Partition, the city was meticulously designed with open spaces, green belts, and sector-wise zoning (Sarin, 1980). According to planning theory, Chandigarh should be a leading city in India. However, Chandigarh is one of India's least densely populated cities and smaller than other Indian state capitals. Why did Chandigarh (10 lakhs) fail to become an urban centre like Bengaluru (84 lakhs), Pune (31 lakhs), or Ahmedabad (56 lakhs)?

One reason for Chandigarh’s stunted growth could be the Punjab New Capital (Periphery) Control Act of 1952—a planning law that was supposed to make Chandigarh better than the unplanned cities of India. The law attempted to create a green, planned, and beautiful Chandigarh per the wishes of the Union Government sitting far away in Delhi. Instead, it made a stunted city that was at odds with the needs of people living and working in and around it. In contrast, cities such as Mumbai, Kolkata, and Hyderabad have evolved into high-density urban hubs, accommodating larger labour markets.

This article examines how Chandigarh’s rigid urban controls shaped its development, the impact of the 1952 Act on its periphery, and how later policies—particularly the 2006 reforms—sought to address these limitations. We analyse the region’s regulations and population trends to understand the cost of curbing development in favour of retaining a city’s “character.”

Chandigarh’s development bottleneck

For 75 years, Chandigarh’s growth as a city has been constrained by the Punjab New Capital (Periphery) Control Act of 1952. The Act set up a 16-kilometre (ten-mile) radius around Chandigarh city and covered parts of Mohali and Panchkula. The Act:

“... extends to such part of the area in the State of Haryana as is adjacent to and within a distance of ten miles on all sides from the outer boundary of the land acquired for the Capital of the State at Chandigarh as it existed immediately before the 1st November, 1966”.

Under the Act, Chandigarh’s peripheral area was off-limits for construction, including roads and infrastructure. The periphery was intended to serve as a buffer zone that would preserve agricultural lands, forests, and open spaces, thereby enhancing the ecological and aesthetic quality of the city (Chalana, 2015). Within this protected zone, no construction, digging, or roadwork was allowed unless approved in writing by the government (Section 5). Breaking this rule led to a fine of up to Rs 10,000 and imprisonment for up to three years (Section 12).

As a result of all the legal restrictions, Chandigarh remained a relatively less dense city compared to other metropolises like Chennai, Hyderabad, and Mumbai, as shown in the table below.

This low density is not what the residents of Chandigarh want, as demonstrated by the large number of illegal constructions in the city’s periphery. Between 1996 and 2005, Punjab’s Urban Development Authority issued over 1,500 notices to residents in the periphery areas (Government of Punjab, 2006). Residents were also often denied utility connections, such as electricity and water, because their construction violated the 1952 law. As a result, several residents filed cases in the High Court to challenge the government's decision to deny the residents utility connections.

All this came to a head in 2003, when the High Court directed the government to review its periphery development control regulations. For 50 years before this direction, the city's horizontal expansion and organic urban growth had remained arrested.

Before and after

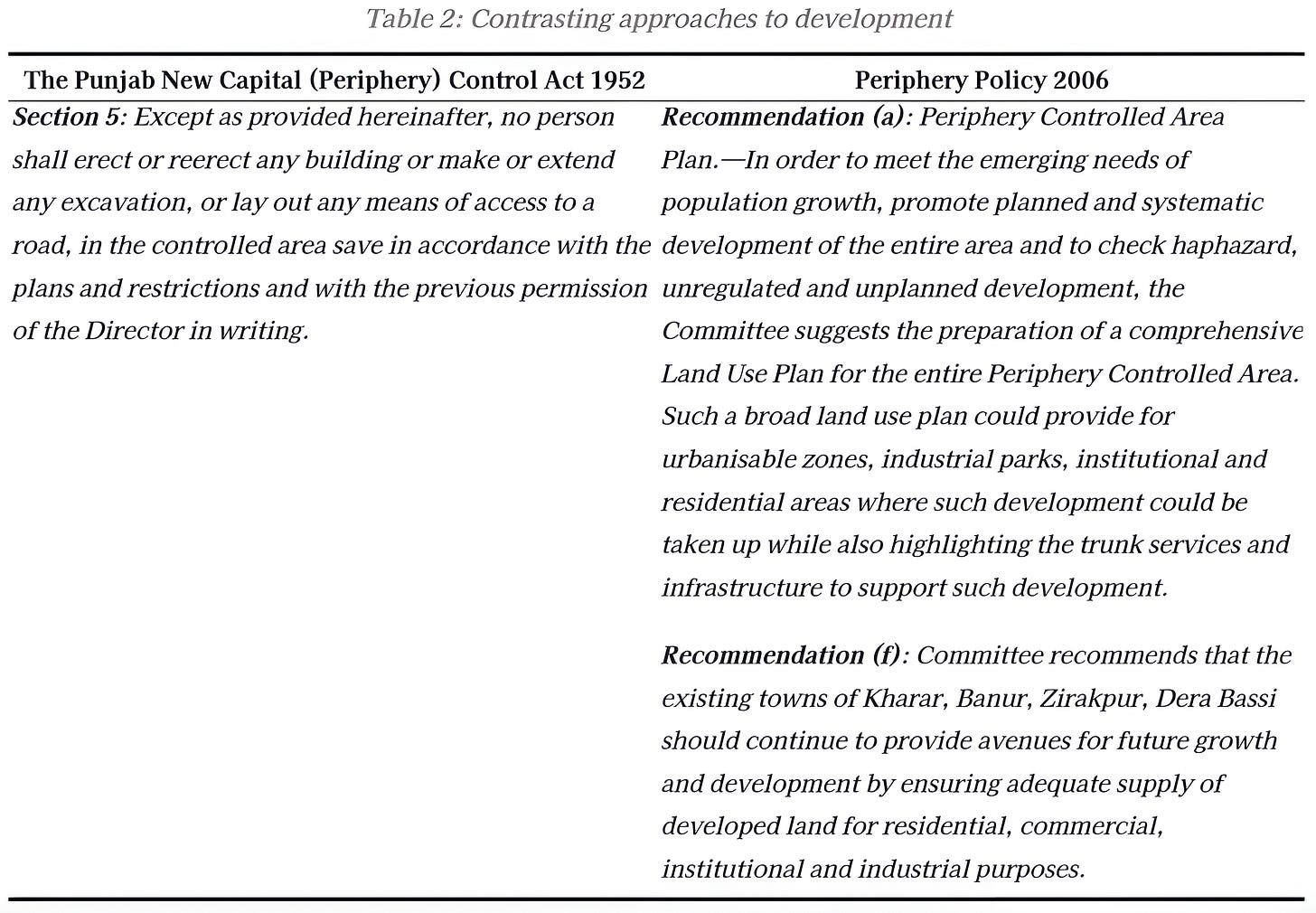

In 2003, the High Court of Punjab and Haryana directed the formation of a committee to study the emergent development in Chandigarh’s periphery and determine policy solutions. The committee recommended the 2006 Periphery Policy, which sought to create a more liberal regulatory framework than the 1952 Act. The 2006 policy created a framework to allow for development in Chandigarh’s periphery, as opposed to the complete ban under the 1952 Act. The table below demonstrates the difference in approach to the development of Chandigarh.

The Policy called for a permissive “plan-based” approach to development, in contrast to the 1952 Act’s strategy, which left development to the discretion of a government official. Under the new Policy, Master Plans were approved for five new towns emerging on Chandigarh's outskirts. Under these plans, each township could develop its real estate for commercial and residential use instead of the complete ban and forced agrarian use under the 1952 Act. The city of Mohali became the first beneficiary of this liberalisation.

How did the policy help?

The policy and the subsequent Master Plans had a measurable impact on the growth of the surrounding areas of Chandigarh, especially Mohali, Panchkula and Zirakpur. Using satellite imagery, the following video captures how Chandigarh and its surrounding cities have developed over 40 years.

The video illustrates a sudden surge in population immediately after the 2006 policy was implemented. As the table below shows, Mohali and Panchkula grew at over twice the rate of other cities in Punjab in the census decade after the 2006 policy was introduced.

The restrictions imposed by the Periphery Act reflect a top-down approach to urban planning, which overlooks organic growth. The Act prevented the natural evolution of satellite cities around Chandigarh. While the legislation aimed to preserve green spaces and regulate unplanned development, it ultimately limited housing availability, economic opportunities, and infrastructure growth. The delayed introduction of the 2006 policy and subsequent Master Plans allowed for some corrections, as reflected in the 2001–2011 census data. The shift underscores how removing restrictive policies reveals people’s preferences—when given a choice, residents and businesses naturally gravitate toward areas with fewer regulatory barriers and better opportunities.

Without considering local economic and social dynamics, planning from a distance often imposes high costs on cities. Chandigarh’s restricted growth forced urban expansion into unregulated areas, capping its economic potential and leading to inefficient land use. The comparison highlights the risks of rigid urban controls. Cities need adaptive policies that allow development in line with economic realities rather than bureaucratic prescriptions. Future urban policies should prioritise infrastructure investment and regulatory flexibility to ensure sustainable, inclusive growth without the constraints of restrictive land-use laws.

References

Chalana, M. (2015). Chandigarh: City and Periphery. Journal of Planning History, 14(1), 62–84.

Government of Punjab. (2006). Periphery Policy (No. 18/35/2002-1HG2/499).

Greater Mohali Area Development Authority. (n.d.). Report of the State-level Committee to recommend a policy framework for the Chandigarh Periphery Controlled Area and regulating constructions therein.

Greater Mohali Area Development Authority. (2006). SAS Nagar Local Planning Area 2006-2031. Government of Punjab.

Greater Mohali Area Development Authority. (2008). Revised Master Plan—Zirakpur. Government of Punjab.

Henderson, J. V. (2010). Cities and Development. Journal of Regional Science, 50(1), 515–540.

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. (2001). Census of India. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner. (2011). Census of India. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India.

Sarin, M. (1980). Chandigarh: Progress and problems of a great experiment. The Round Table.

Shalimar Estates Pvt. Ltd. vs. The Union Territory of Chandigarh and Others, Civil Writ Petition No. 17753 of 2005 (High Court of Punjab and Haryana 20 August 2013).

Sham Lal v. The Union Territory and Ors., Civil Writ Petition No. 6735 of 1974 (High Court of Punjab and Haryana 29 April 1977).

The Punjab New Capital (Periphery) Control Act (1952).

The Times of India. (2009, June 2). ‘Periphery control act being violated’.

Sargun Kaur, Shubho Roy, and Rohan Ross are researchers at Prosperiti.