#46: Too safe to work

A single condition under night shift regulations increases a woman’s employment cost by 86%

India aims to raise the female labour force participation to 70% by 2047 under the ‘Viksit Bharat’ vision. The government is drafting a national policy focused on caregiving infrastructure and skilling to support this effort. Although India’s female labour force participation is improving, it remains low at 32.8%.

This low female labour participation is surprising, given that the Constitution contains provisions to protect and encourage women in the workforce. The Constitution allows the state to make “...special provision for women and children” [Article 15(3)]. This provision allows the legislature to make special laws to discriminate in favour of women and children, including employment matters. Similarly, the Directive Principles of State Policy require the state to ensure that “...men and women equally, have the right to an adequate means to livelihood” [Article 39(a)]. The state is also obligated to make laws that promote “equal pay for equal work for both men and women” [Article 39(d)]. With such progressive laws in the Constitution, why do Indian women lag in participating in the workforce?

One possible explanation is that women are being discouraged by the very progressive laws designed to encourage their inclusion in the workforce. These progressive laws place such burdens on employers that it may be economically unviable to employ women. Instead of employing women, employers may simply not hire women to avoid the burdens placed by law. In this article, we examine how protective labour laws governing night shifts affect the decision to hire women. Using Tamil Nadu’s Factory Rules as a case study, the article illustrates how inclusion provisions in factory laws function in reality. We quantify the regulations to show how legal conditions across states increase the cost of employing women at night.

Tamil Nadu’s laws: an illustration

Tamil Nadu’s laws are examples of how laws meant to protect and encourage women can make it more difficult for them to find jobs and work towards autonomy and prosperity. State regulations make hiring of women in the night shift difficult via conditions related to Section 66(1)(b) of the Factories Act 1948. The Tamil Nadu Factories Rules state:

“The occupier of the factory shall ensure that women workers employed in night shift shall not be less than ten and not less than two-third of the total strength of workers and one-third of the supervisors/ shift in charge/ foreman shall be women; as well;”

(Rule 84B(6), Tamil Nadu Factories Rules, 1950)

Consider a hypothetical textile factory in Coimbatore with 25 workers and a management willing to hire women for night shifts. This factory must hire at least ten women and ensure they make up two-thirds of the night shift, even if one woman is to be employed on the night shift. The quorum rule discourages the factory from hiring women unless it is willing or able to meet the specified quotas.

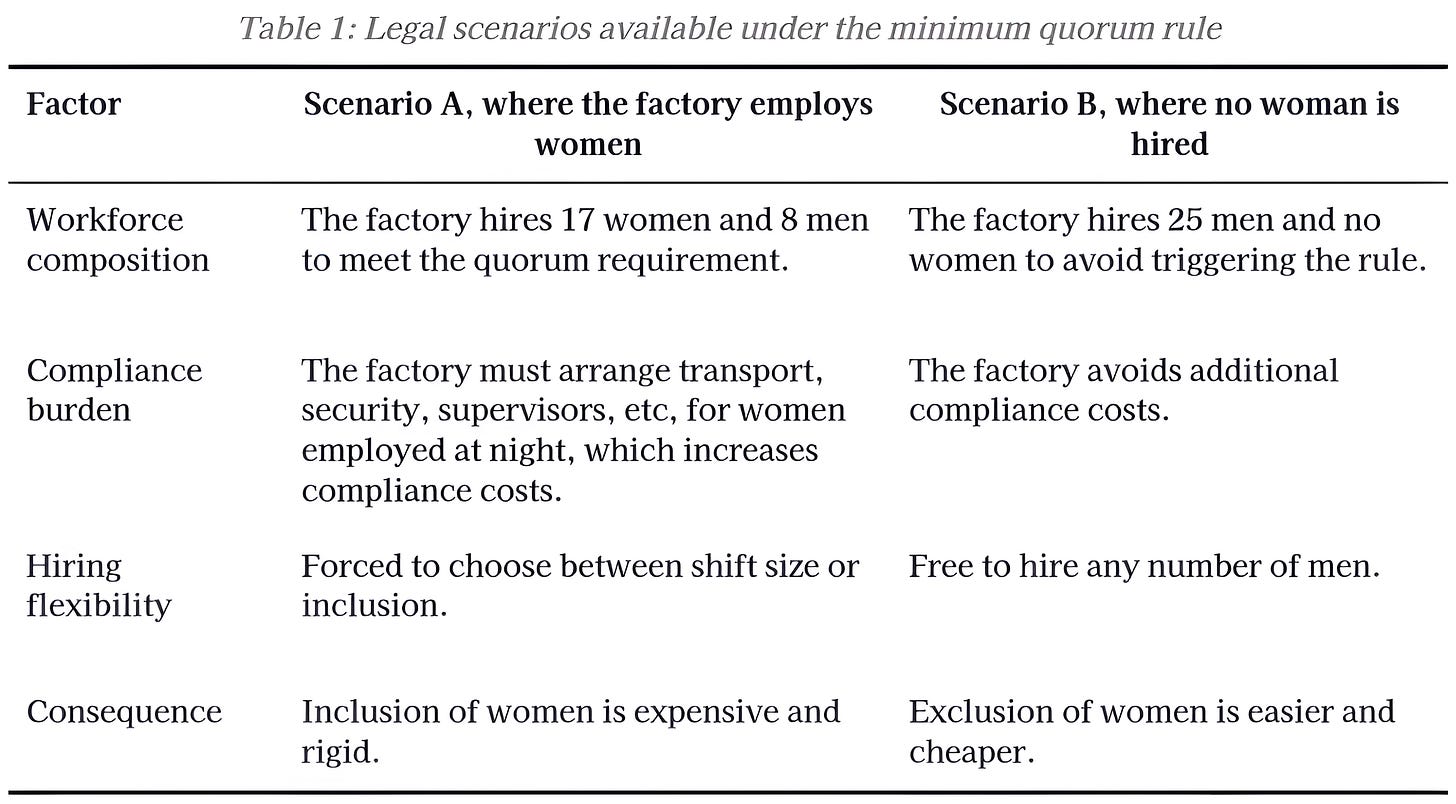

The 25-worker factory in Coimbatore must choose between two legal scenarios under this rule, as shown in Table 1.

The state imposes the quorum rule without considering that factories may not have enough women workers. Even in Tamil Nadu, where women’s employment is relatively advanced compared to other states, women make up only 45% of textile workers on average (Government of India 2023). This means factories may not be able to easily assemble a full night shift with predominantly staffed by women. As a result, employers may choose not to hire women at all to avoid triggering the quorum condition.

Mandatory transport provisions for night-time employment

In addition to quorum rules, our hypothetical factory must also arrange transport when employing women at night. This further raises the cost of employing women. Factories in Tamil Nadu are required by law to provide transport when hiring women for night shifts. As per the Rules:

“The occupier of a factory shall provide... separate safe transportation from the factory premises to the nearest point of their residence to the women workers in night shift.”

(Rule 84B(8) of Tamil Nadu Factories Rules, 1950)

In Tamil Nadu, the minimum wage is Rs 8,646 per month. However, the transportation rule may add Rs 7,425 cost for each female worker. This cost amounts to 85.9% of her monthly salary.

The factory’s obligation to provide transport for women employed at night can affect its profit margin. Labour costs are a significant component of the textile industry at 14%, compared to 6% in food processing (KLEMS, 2024). The labour cost (under simple assumptions) would fall to 7.53% if our hypothetical factory employed women at night. Currently, India’s textile industry earns a profit of 8.53% (KLEMS and NAS database). This profit would rise to 14.88% if the factory operated without the transport rule. Thus, a rational employer may avoid hiring women for night shifts to avoid 42% fall in the profit margin. Table 2 below shows the impact of the transport requirement on the profitability of our hypothetical factory.

The cost of complying with a single condition increases employment costs and reduces profitability of the sector. In our simplified hypothetical scenario, factories would earn lower profits if they employed women at night.

Separate vs Combined Transportation Costs

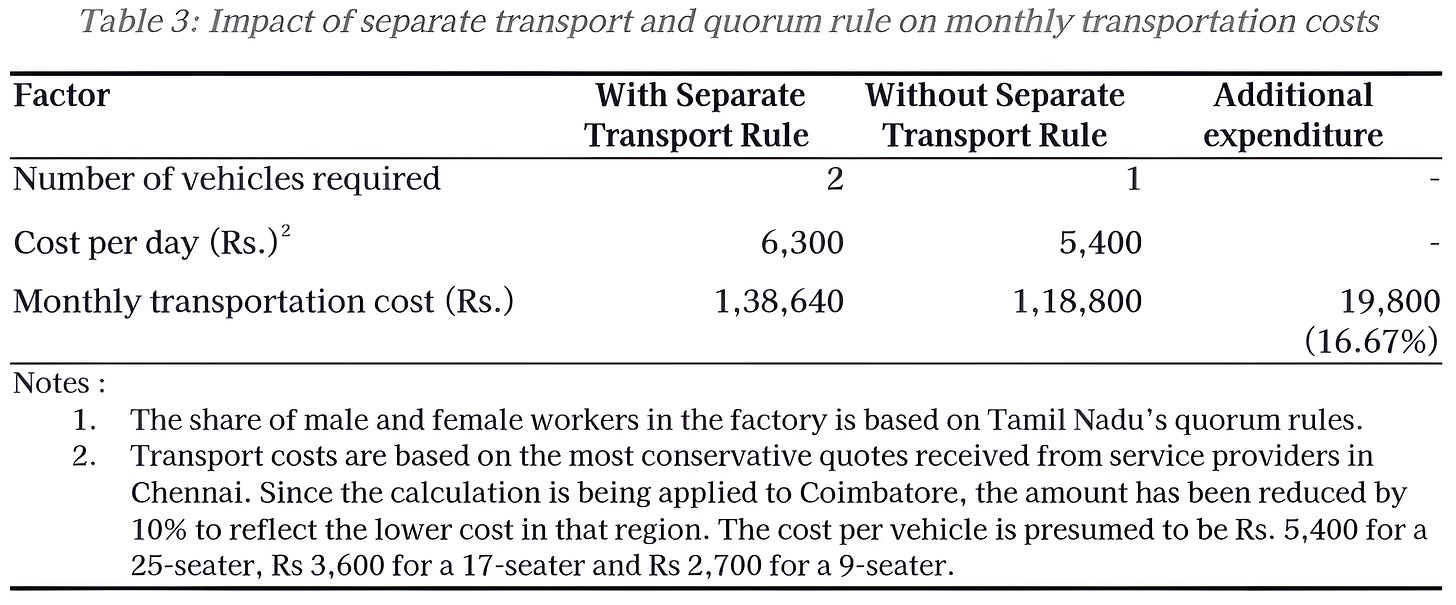

Tamil Nadu’s laws do not stop at requiring employers to provide transportation for women working at night. The law goes on to require that the transportation be “separate” [Rule 84B(8), Tamil Nadu Factories Rules, 1950]. This single word further increases the cost of transportation. Separate transportation services increase total costs by 16.67%—from Rs. 1,18,800 to Rs. 1,38,640—once the quorum rule is triggered, as illustrated in Table 3.

Now, if all 25 night shift workers were men, the employer would not be required to provide transportation. The entire cost of transportation would be eliminated. Further, the factory could retain its full 25-person workforce without restructuring shifts or incurring additional expenses.

Infrastructure requirements triggered by female employment

After transportation, Tamil Nadu’s laws require factories to build additional workplace infrastructure to comply with labour laws governing women’s night shifts. Canteens are typically required only in factories employing more than 250 workers [Section 46, Factories Act, 1948]. However, in Tamil Nadu factories employing women at night must provide segregated space for women and men for canteen facilities, regardless of their size. The Rules state:

“The occupier of a factory shall provide separate dining facilities … to the women workers in night shift.”

(Rule 84B(8) of Tamil Nadu Factories Rules, 1950)

This rule burdens a 25-worker factory with an additional Rs 4,02,702 in expenses, as illustrated in Table 4 below.

Our hypothetical factory could avoid all these costs by just employing men at night. The laws may seem progressive on paper, but when analysed from an economic point of view, they in fact encourage employers to discriminate against employing women in Tamil Nadu.

Other States’ Laws

Tamil Nadu is not the only state that imposes conditions on women’s employment at night. 16 other states allow women to be employed in factory night shifts subject to employers meeting conditions. In these states, an employer must comply with 19 or more conditions to hire women at night. These conditions include staffing, transport, security, in-factory infrastructure, medical services, maternity and leave benefits and anti-harassment measures-all of which could be avoided by simply not employing women at night.

The quorum requirement discussed in the Tamil Nadu illustration is common across many states, as shown in Table 5. Factories can hire women for night shifts only if they employ them in fixed batches or maintain specific gender ratios among workers and supervisors. For instance, in seven states, employers must ensure that at least one-third of all supervisors are women. This condition creates recruitment challenges in industries with fewer women in managerial roles. Such regulatory requirements also force factories to either overhire women or avoid hiring them altogether.

Like Tamil Nadu, other states also mandate transportation for women working night shifts. But, some states impose further conditions on how employers must arrange transport for women. For instance, Karnataka commands that employers not only provide transportation, but such transportation meet the following condition:

“Careful selection of routes shall be made in such a way that no women employees shall be picked up first and dropped last...”

(Section 66(a)(xv), the Factories (Karnataka Amendment) Act, 2023)

Such rules may increase fuel costs for staff transportation and make route planning more complicated.

Further, some states mandate that there should be female security guards in transport vehicles and factory premises. Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Karnataka require the employer to provide security guards, including female security guards, in transport vehicles.

In addition to transport security, some states require employers to provide security within factory premises for women employed at night. For instance, states like Assam, Haryana, Karnataka, Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Telangana require that “Sufficient women security shall be provided... at entry as well as exit point” in factories. The irony of these laws is that the female security guards hired to protect women workers would themselves require safe transport and security, further compounding employer obligations.

Finally, some states impose limits on how many consecutive night shifts women can work. For instance, in Maharashtra, women cannot work night shifts “for more than one week” [Rule 102-B (13), Maharashtra Factories (Amendment) Rules, 2016]. This restriction creates barriers to women’s employability in night shift roles and affects their competitiveness in the job market. The need to rotate women out of night shifts adds complexity to scheduling and resource allocation, making factories more likely to hire male workers.

Privatising public goods failure

Labour laws regulating women’s work at night privatise public goods, which is the phenomenon where a law transfers the duties of the state (to provide public goods) to private parties. This transfer seems attractive at first glance, but has the unintended consequence of deterring employers from hiring women.

Surveys and studies indicate that public spaces and transport remain unsafe for women in India. Public spaces and transport in India do not guarantee women's safety. Many women avoid using public transport at night due to safety concerns. This is reflected in the She Shakti Suraksha Survey 2025, which found that only 36% of women in Indian cities felt safe using public transport after dark. States have responded to this problem by making employers responsible for women’s safety.

Women’s safety, like the absence of crime, is a public good that should be provided by the state, irrespective of their employment status (Spiegel 2003). The government creates a ‘public goods failure’ when it does not create a safe environment for women. This failure makes it dangerous for women to work or travel at night.

In India, labour laws transfer the duty to provide these public goods from the government to the private employers. However, this does not have the intended effect of making society safer for women. Instead, employers see employing women as a burden and avoid doing it in the first place. This is because if the employer does not employ women, the employer escapes the duty to provide safety. Research also shows that the costs imposed on employers for integrating women into the workforce act as a barrier to female employment in the private sector (Miller, Peck, and Seflek 2019).

The state’s response to public goods failure not only imposes costs on employers but also curtails women’s freedom to choose. The reduction of freedom has been studied in Legal Paternalism (Feinberg 1971), which argues that well-intentioned restrictions can undermine individual autonomy by preventing individuals from taking informed risks in pursuit of meaningful opportunities. Indian labour laws demonstrate legal paternalism when it comes to employing women at night. Women willing to work at night cannot do so unless employers meet special conditions, even if the women do not require such conditions. For example, the employer is not exempted from providing a canteen, even if the women employees have no need for it and could have eaten their meals at their workbenches. Therefore, women cannot get employed even if they have no need for the protection, or would be better off being employed with less protection. Our labour laws substitute state judgment for individual agency, thereby reducing women’s economic freedom.

Vicious cycle of low female workforce

States, by limiting women’s economic freedom, may be creating a vicious cycle of low female workforce, where progressive labour laws contribute to the problem instead of reducing it. The existing labour laws are self-defeating in nature. Figure 2 shows how this vicious cycle plays out.

This vicious cycle perpetuates the problem of women’s exclusion from the workforce rather than solving it. Research also shows that labour regulations meant to protect workers end up excluding women from the labour market (Montag 2013).

This vicious cycle can be broken by shifting responsibility for women’s safety back to the public sector, where it belongs. Women’s safety is the responsibility of the society at large and not limited to the employers of women. When states treat safety as a workplace condition and not as a public function, they confine women’s economic participation to contexts where employers are willing to bear the burden of protection. Labour laws intended to empower women ultimately restrict their opportunities, illustrating how well-intended regulatory measures can have unintended consequences.

References

Feinberg, Joel. 1971. “Legal Paternalism.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 1 (1): 105–24.

Government of India. 2023. “Annual Survey of Industries, 2022-23.” Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation.

Miller, Conrad, Jennifer Peck, and Mehmet Seflek. 2019. “Integration Costs and Missing Women in Firms.” w26271. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Montag, Josef. 2013. “Is Pro-Labor Law Pro-Women? Evidence from India.” Centre for Economic Research and Graduate Education- Economic Institute.

Spiegel, Menahem. 2003. “Public Safety as a Public Good.” In Markets, Pricing, and Deregulation of Utilities, edited by Michael A. Crew and Joseph C. Schuh, 183–200. Boston, MA: Springer US.

Bhuvana Anand, Naveena Pradeep, and Shubho Roy are researchers at Propseriti.

So, how can we empower women to work during night shift? Shifting the cost back to the public is more of a structural issue and it would be difficult to explain to the government that these costs shouldn't be borne by the private sector?