#43: Labour flexibility for the win

Boosting jobs and economic growth through employment regulation reforms

Introduction

Manufacturing has historically driven the transition from poor agrarian societies to affluent industrial ones. For India, manufacturing can play a critical role in India’s transition since it is an agrarian society with an ample supply of labour. Manufacturing can absorb this labour to create productive jobs that improve incomes and living standards. However, labour regulations in India may impede this transition (Thomas, 2012).

India's transition to manufacturing depends on India’s ability to attract manufacturing. India can attract manufacturing facilities only if it can compete with its International counterparts in terms of productivity of Indian factories compared to their international counterparts (Amirapu & Gechter, 2020). India's regulations should align with global standards to achieve global competitiveness. These regulations govern factories and manufacturers across four key axes: hiring, operations, redundancy, and compliance.

Labour regulations in India hamper the country's global manufacturing competitiveness in four key areas (Besley & Burgess, 2004). Hiring restrictions stifle firms' ability to scale and adapt to market demands. Operational constraints prevent Indian factories from optimising their processes to match the productivity of international rivals. Redundancy rules make workforce adjustments prohibitively expensive for employers. Compliance requirements saddle Indian businesses with administrative burdens that many international competitors do not face. This regulatory rigidity leaves Indian manufacturers ill-equipped to navigate rapid changes in global markets. As a result, these regulations significantly disadvantage Indian firms and undermine their ability to compete on the world stage.

The impact of these regulations on India's manufacturing sector varies, but all contribute to its lagging global position (Subramanian & Chatterjee, 2020). Hiring and operational regulations have the highest impact on growth and innovation. Reforms in these areas could dramatically boost productivity and international competitiveness but are also difficult to reform because of political considerations. Redundancy regulations face less political opposition but deliver less impact. Compliance reforms can provide a modest impact but face low political resistance (Anant et al., 2006). Without comprehensive regulatory reform across all areas, India's dream of becoming a global manufacturing powerhouse may remain out of reach.

Manufacturers in India have responded to these regulations through two primary strategies: by remaining small and by increasing capital intensity to levels higher than in countries with comparable per-capita GDP, despite access to a large labour force (Department of Economic Affairs, 2019; Dougherty et al., 2010). Almost 80% of factories in India employ fewer than 100 people, with 67% employing fewer than 50 (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, 2024). India’s economy ranked 56th on GDP per capita but ranked 28th on capital intensity per worker (Hasan et al., 2013).

Indian policymakers have initiated various reforms to ease the compliance burden on employers and boost manufacturing jobs and wages. However, recent research suggests that this approach may fall short. While a step in the right direction, easing compliance burdens may not suffice. Addressing substantive restrictions on hiring, operations, and redundancy could significantly improve employment and productivity.

Researchers have extensively examined the impact of redundancy laws, but research on operational regulations is limited. These operational restrictions govern the day-to-day functioning of businesses and directly affect productivity. By addressing operational restrictions, policymakers can unlock greater job creation, income, and economic growth potential in India's manufacturing sector.

Labour laws and Business operations

India regulates occupational safety, health, and working conditions for factory operations. These regulations govern every aspect of manufacturing establishments, from dictating the physical design of facilities to limiting the hours workers can work. These mandates determine a factory's operational capabilities and affect a manufacturer's ability to meet peak demand by imposing restrictions on working hours and overtime. These regulations can impact a company's export competitiveness by adding compliance costs and operational constraints that competitors may not face in countries with more permissive labour laws.

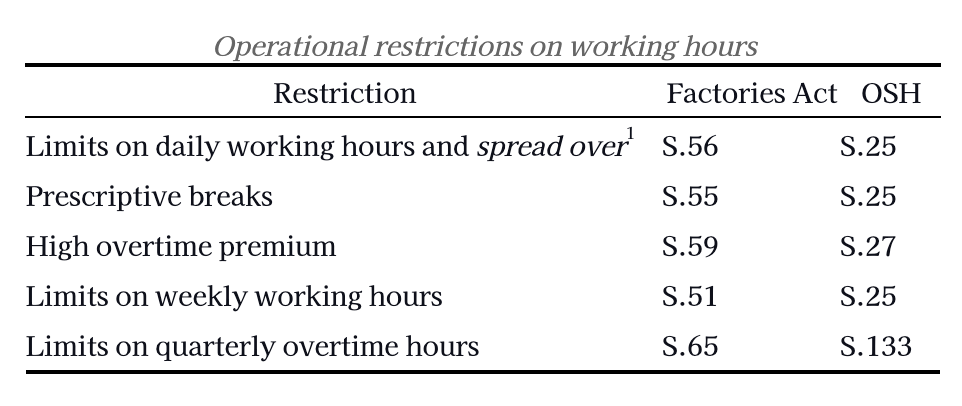

Recognising the need to be more competitive, states like Karnataka and West Bengal have proposed increasing working hours (Telegraph India, 2024; The Times of India, 2024). The Economic Survey of India also recognises the cost of inflexibility in working hours (Department of Economic Affairs, 2024). These restrictions, from the Factories Act, limit the kinds of agreements employers and employees can reach. Five ways working hours are restricted are:

Countries generally regulate some of these five aspects, but India is unique in two ways: We impose all five restrictions and are among the strictest on each (The World Bank, 2003). These regulations frequently result in unintended consequences that curtail flexibility and reduce earning potential.

Daily limits on working hours

India restricts two things: the number of hours a worker can ordinarily work and the total number of hours a worker can spend at the workplace (spread over). Under the law, Indian workers are allowed up to 9 regular working hours per day and can stay at the workplace for a maximum of 10.5 hours.

The restrictions on working hours and spread over significantly reduce the flexibility for workers and employers to negotiate work schedules that might be mutually beneficial. For example, if a worker starts their shift at 8 AM, they must finish by 6:30 PM, irrespective of the production demands or the worker's readiness to work longer. By comparison, Vietnam permits ten regular hours of work per day and a 12-hour spread over. The higher spread over allows workers who start their shift at 8 AM to continue working until 8 PM, offering greater adaptability.

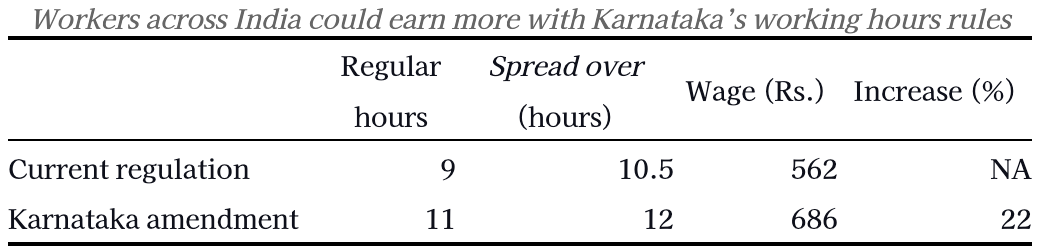

Inflexibility impedes productivity and restricts workers' potential earnings, particularly in sectors with variable demand or seasonal surges (Anand et al., 2023). Recently, Karnataka increased the daily spread over for factories to 12 hours but remains the only Indian state to do so. Increasing the spread over to 12 hours increases the daily working hours from 9 to 11. The 22% increase in working hours could increase the daily wage of workers in manufacturing from Rs. 562 to Rs. 686 (Labour Bureau, 2023).

Prescriptive breaks

In addition to regulating the working hours, regulations mandate workers take a 30-minute break after every 5 hours of continuous work. Enforcing this rigid break schedule can disrupt productivity and workflow (Anand et al., 2023). A comparison between Telangana and Singapore shows how the legally mandated break disrupts normal workflow.

Telangana allows a spread over of 12 hours for commercial establishments, so shifts that start at 8:00 a.m. can end at 8:00 p.m. Singapore also has the same limit on the maximum time employees can spend at the workplace. However, Telangana workers must take a 30-minute break every 5 hours. In contrast, Singaporean workers get a longer break of 45 minutes, but after 6 hours.

Due to Telangana’s restriction, Indian workers are left with a rump shift of 1 hour after their second break. On the other hand, Singaporean workers get two long, uninterrupted shifts (6 hours and 5 hours 15 minutes). Telangana’s law makes a 12-hour spread over unviable. In Telangana, workers have three shifts (5 hours, 5 hours, 1 hour). In Singapore, workers have two shifts (6 hours, 5 hours, 15 minutes). The difference in total hours worked is only 15 minutes, but the break is concentrated in one slot in Singapore, allowing 12-hour shifts to be viable.

High overtime premiums

India's regulation of working hours creates a problematic interaction between strict hour limits and exorbitant overtime premiums. The country's daily hour limits often align with global norms, but its overtime premium is the highest globally. Indian law requires factories to pay workers double their regular wage for overtime hours. This premium significantly exceeds rates in both developed and competing developing countries. Strict limits on regular working hours compound this issue. These regulations create a perverse incentive structure that undermines the worker protections they aim to provide.

Employers face a dilemma in industries where employee income contributes significantly to the cost of goods. They must either bypass overtime regulations informally or avoid offering overtime altogether. Basic analysis indicates that wage rates at the 2.00 premium are so high that employers may find it economically unviable to use overtime labour and remain profitable (Dandekar & Roy, 2023). Overtime would become viable if regulators reduced the mandated overtime premium to the ILO-recommended 1.25.

Workers could see a 28% wage increase if the mandated overtime premium were 1.25 instead of 2.00. Consider a Telangana hotel industry worker who wishes to work nine regular and two overtime hours. Current regulations permit this schedule but require employers to pay double the regular rate for overtime. This policy results in a total wage equivalent to 13 hours of pay. However, the double overtime rate makes the profit margin negative for employers, preventing them from offering overtime. Consequently, workers lose these additional hours, reducing their total pay to just 9 hours.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) recommends an overtime rate of 1.25 times the regular wage. If India adopted this rate, a hypothetical worker could work their desired nine regular and two overtime hours since profit margins remain positive. This schedule would result in pay equivalent to 11.5 hours, striking a balance between worker earnings and employer profitability. Such a change could benefit both parties, increasing worker income while keeping labour costs manageable for businesses.

Weekly limits on working hours

In addition to limiting daily income, Indian law also places income-reducing limits on the workweek. The law allows workers to work for nine regular hours a day. A six-day workweek would enable workers to work 54 hours a week. But, Indian law limits the regular workweek to 48 hours. This limit has to be met every working week. In contrast, countries like Japan allow workers to average the regular hours requirements over multiple weeks. While individual week limits in India are comparable to other manufacturing hubs, averaging daily work limits allows workers more flexibility, which may increase their income. This flexibility is not allowed for Indian workers (Anand et al., 2023). The added flexibility helps workers earn additional income during times of high demand. Seasonal goods may require an increased number of hours for a short duration. Similarly, producing goods for a new item launch, like a new iPhone, may need additional work close to the launch date.

Indian laws limit worker flexibility and income. These laws restrict income opportunities by raising employment costs, potentially driving manufacturers toward automation to lower expenses (Apple Insider, 2024). In Japan, weekly working hour limits are averaged over considerably longer periods, granting workers more flexibility even though the regular weekly working hours are lower than in India (40 hours compared to 48). For instance, iPhones are usually released in September, and the October-December period sees the highest sales, accounting for 34% of yearly revenue, compared to 22% in the previous quarter (Macrotrends, 2024). The lead-up to the launch requires ramping up production. If there was a critical five weeks of production in the quarter that required an increase in worker hours, Japanese workers can work extra hours in that period and compensate by working less in other weeks in the quarter. Over 13 weeks, a Japanese worker can work 520 hours (13*40). An Indian worker can work 624 hours, 104 hours more. However, an Indian worker is limited to 48 hours every week. A Japanese worker could work 70-hour weeks for five weeks and 21.25-hour weeks for the remaining eight weeks in the quarter without breaching the 520-hour limit.

Quarterly limits on overtime hours

Indian workers can work additional hours using overtime, but India also limits the number of hours a worker can use. Indian states limit overtime to between 75 and 115 hours per quarter, depending on the state. Governments in other countries set significantly higher limits for overtime hours. For example, Malaysia allows up to 312 overtime hours per quarter, while Singapore permits 216 hours. These higher limits in other countries enable workers to increase their earnings through overtime work.

The freest Indian workers can earn for 25% fewer hours a quarter than any Malaysian worker. An Indian worker can work 624 hours of regular work per quarter, while a Malaysian worker can work 585 regular hours per quarter. In addition, the freest Indian worker can work 144 overtime hours in a quarter, while a Malaysian worker can work 312 overtime hours. If overtime is compensated at 1.5X, an Indian worker can earn 840 hours of income a quarter, while a Malaysian worker can earn 1,053. Increasing the quarterly cap on overtime hours could benefit Indian workers.

Conclusion

Current labour regulations aim to protect workers but inadvertently limit job opportunities and earning potential, harming the employees they intend to safeguard (Besley & Burgess, 2004). Policymakers could consider several reforms to address these challenges and bolster India's global manufacturing competitiveness while improving workers' incomes.

India's overtime premium, currently at twice the regular wage rate, ranks among the highest globally. Lowering this to 1.5 or even 1.25 times the standard rate, in line with international norms and ILO recommendations, could incentivise employers to offer more overtime opportunities. This change would increase workers' earning potential. Policymakers should also consider extending the daily spread over limits from 10.5 to 12 hours, as implemented in Karnataka. Such a change could provide greater flexibility in shift scheduling, potentially increasing daily wages and allowing for more adaptable work arrangements to meet varying production demands.

Revising prescriptive break schedules to allow for longer continuous work periods, similar to Singapore's approach, could enhance productivity and worker earnings. This reform would enable more efficient use of working hours while still ensuring adequate rest periods. Additionally, permitting averaging of weekly working hours across multiple weeks, as seen in countries like Japan and Germany, would offer greater flexibility to meet seasonal demands. Companies could then respond more effectively to fluctuations in production needs, allowing workers to earn more during peak periods.

Relaxing quarterly overtime limits from 75-144 hours to align more closely with countries like Malaysia (312 hours) or Singapore (216 hours) could significantly boost workers' income potential. This reform would provide more opportunities for employees to increase their earnings through additional work hours when desired. By implementing these changes, India can balance worker protection and economic growth.

Increasing workplace flexibility can improve India's manufacturing competitiveness on the global stage and enhance workers' income and job prospects. As India continues to navigate its path towards becoming a manufacturing powerhouse, thoughtful labour reform will prove crucial in unlocking the full potential of its vast workforce and driving economic prosperity. Carefully implemented reforms could create a more dynamic labour market that benefits workers and employers, fostering sustainable economic growth and improved living standards.

References

Amirapu, A., & Gechter, M. (2020). Labor Regulations and the Cost of Corruption: Evidence from the Indian Firm Size Distribution. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 102(1), 34–48.

Anand, B., Roy, S., & Saxena, P. (2023, October 4). Lower the bar, increase the earnings [Substack newsletter]. Prosperiti Insights.

Anant, T. C. A., Hasan, R., Mohapatra, P., Nagaraj, R., & Sasikumar, S. K. (2006). Labor Markets in India: Issues and Perspectives. In J. Felipe & R. Hasan (Eds.), Labor Markets in Asia: Issues and Perspectives (pp. 205–300). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Apple Insider. (2024, June 24). Apple steps up its goal for automation in iPhone assembly. AppleInsider.

Besley, T., & Burgess, R. (2004). Can Labor Regulation Hinder Economic Performance? Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 91–134.

Dandekar, S., & Roy, S. (2023, August 23). Double or Nothing [Substack newsletter]. Prosperiti Insights.

Department of Economic Affairs. (2019). Economic Survey 2018-19, Volume I. Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

Department of Economic Affairs. (2024). Economic Survey 2023-2024. Ministry of Finance, Government of India.

Dougherty, S., Herd, R., & Chalaux, T. (2010). What is holding back productivity growth in India ?: Recent microevidence. OECD Journal: Economic Studies, 2009(1), 1–22.

Hasan, R., Mitra, D., & Sundaram, A. (2013). What explains the high capital intensity of Indian manufacturing? Indian Growth and Development Review, 6(2), 212–241.

Labour Bureau. (2023, July 7). Occupation Wages. Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India.

Macrotrends. (2024, June 30). Apple Revenue 2010-2024 | AAPL.

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. (2024). Summary Results for Factory Sector 2021-22: Annual Survey of Industries.

Subramanian, A., & Chatterjee, S. (2020, October 2). India’s Export-Led Growth: Exemplar and Exception. Ashoka University: Leading Liberal Arts and Sciences University.

Telegraph India. (2024, June 24). Nine-hour work day at Bengal IT sector.

The Times of India. (2024, July 22). Karnataka government planning proposal to extend IT employees’ working hours to more than 12 hours a day. The Times of India.

The World Bank. (2003). Doing Business 2004: Understanding Regulation. The World Bank.

Thomas, J. J. (2012). India’s Labour Market during the 2000s: Surveying the Changes. Economic and Political Weekly, 47(51), 39–51.

Bhuvana Anand, Abhishek Singh, Shubho Roy, and Arjun Krishnan are researchers at Prosperiti.

Very comprehensive analysis of a complex legacy. In my opinion, apart from these extremely valid points the the wage structure based on the skill levels such as NSQF Levels too needs to be optimised.