#42: Week Ideas

To make a 1,000 phones, a factory in Japan needs 40% fewer workers than in India

India aspires to become a global manufacturing hub, and to this effect, the central government has launched multiple schemes like Make in India, Production Linked Incentives, and Ease of Doing Business. These schemes have shown results as India's electronics exports have increased from $10.5 to $32 billion within 5 years. The country's performance, while improving, still lags behind other Asian manufacturing centres. India ranks 21st in global electronic exports, trailing behind countries like the Philippines (20th), Thailand (15th), Japan (11th), and Korea (7th).

One reason India trails other manufacturing centres could be labour regulations. These regulations, designed for 19th-century industries with steady year-round production like steel and textiles, fail to accommodate modern manufacturers' needs. In the 21st century, manufacturers must rapidly scale production up and down to meet seasonal demand cycles, but India's rigid labour framework prevents this flexibility.

Manufacturing iPhones: Seasonal demand

Every September, people in India and around the world line up in long queues to purchase the latest iPhones. These launch-day crowds signal the start of a peak sales period that stretches through Christmas and New Year’s. iPhone demand slows and stabilises before the next launch cycle.

To meet the variable demand, manufacturers must adapt their production cycles. iPhone manufacturers can begin production only a few months before launch after finalising components and designs. These manufacturers must ensure phones reach retailers worldwide in time for September launches, just as demand peaks. Manufacturers must increase production hours above regular levels to meet pre-launch production targets. They can achieve this through two approaches: extending the working hours of existing workers or hiring additional workers for the peak period.

Hiring temporary workers for peak production reduces manufacturers' competitiveness by increasing training costs and lowering productivity. Manufacturers could address seasonal surges by increasing work hours during pre-launch production periods, compensating with reduced hours during slower months. This flexibility around work hour limits allows manufacturers to maintain a stable, trained workforce while meeting seasonal production demands. However, India's labour laws prevent manufacturers from adopting flexible scheduling practices.

Worker flexibility: India v. Japan

While India allows more hours than Japan, it offers less flexibility. India allows 48 working hours a week, 20% more than Japan’s 40-hour limit. However, Indian workers must meet this limit every week, while Japan offers multiple levels of flexibility. The table below compares labour regulations in India and Japan on weekly working hours.

Japanese manufacturers can optimise their workforce by spreading working hours across weeks, months, quarters, or even a full year. Indian manufacturers, in contrast, must adhere to a 48-hour weekly schedule. To understand how these regulatory differences shape manufacturing operations, let's examine two iPhone manufacturing facilities - one in India and one in Japan.

An illustration

An iPhone factory illustrates how different labour rules affect workforce requirements. Consider a facility that must produce 1,000 phones annually, each requiring 40 hours of labour. This production target translates to 40,000 manhours per year. If the factory maintains the same production schedule throughout the year, it needs 770 manhours per week (40,000 manhours /52 weeks). Assuming the same productivity, India can meet this demand with fewer workers than Japan.

India's 48-hour work week gives manufacturers an advantage when the manhours required are stable throughout the year. These manufacturers need fewer workers than their Japanese counterparts to achieve the same production hours. With a 40-hour work week, Japanese manufacturers must hire 18% more workers, three additional employees, to match India's manhours. This advantage, however, depends on steady production requirements.

iPhone production requirements do not remain stable throughout the year. The launch quarter sees a high number of sales followed by a dip. The quarterly revenue of Apple based on iPhones sales reflects this pattern. The highlighted quarter is the highest of the year followed by a dip in subsequent quarters.

To meet this demand, iPhone manufacturers require more production hours leading up to the launch than the rest of the year. If the annual consumption of iPhones were 1,000 units, the demand would be distributed unevenly through the year. The uneven production requirements create challenges for workforce management, particularly during peak production periods.

The strategies manufacturers can use to address workforce management depend on labour laws. As shown in table 1, Japanese manufacturers are allowed to offset increased hours in one week with lower hours in subsequent weeks. This flexibility allows workers to meet the 40-hour weekly limit across months, quarters, or even the full year to match production with demand. Indian manufacturers are not permitted this flexibility.

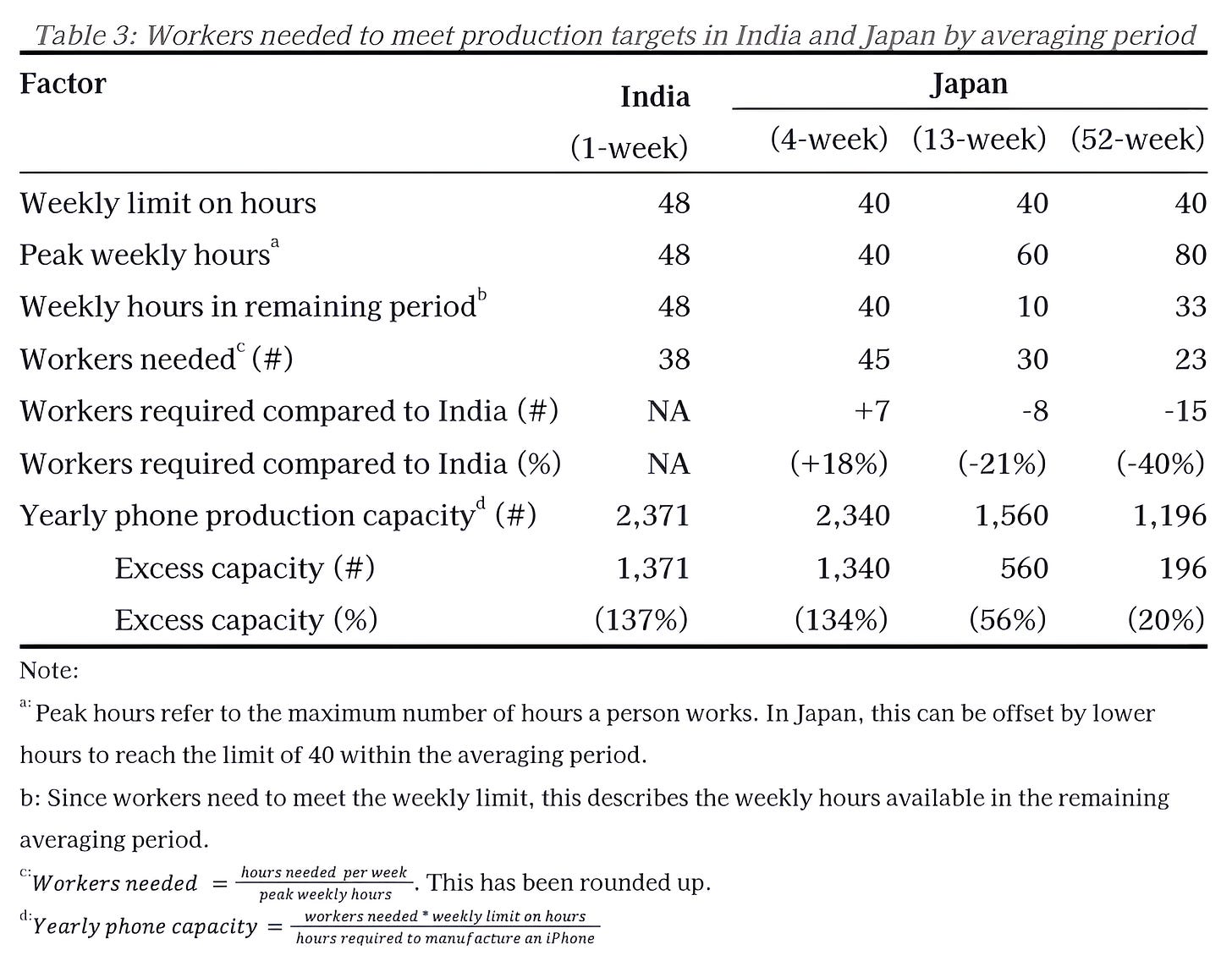

This flexibility becomes crucial during the launch period. iPhone production begins around eight weeks before launch. In those eight weeks, 360 phones need to be produced, which requires 14,400 manhours. This is approximately 1,800 manhours a week. The table below shows how India and Japan can meet this target.

The table above shows India's 48-hour weekly limit provides a competitive advantage in production hours over a year. However, this advantage diminishes in manufacturing sectors with uneven production schedules. Without hour-averaging provisions, manufacturers must maintain large workforces to handle production peaks. In contrast, Japan allows fewer weekly hours but provides a flexible averaging system that enables manufacturers to adapt workforce hours to match production needs. Japanese manufacturers can strategically deploy their workforce, increasing hours during peak periods and reducing them during slower times, while keeping their skilled workers employed year-round.

Conclusion

The analysis shows how different approaches to work hour regulation affect manufacturers' ability to meet seasonal demand. Under India's fixed 48-hour weekly limit, manufacturers need larger workforces to handle production surges, leading to excess capacity during slower periods. Japan's system of work hour averaging, particularly its annual averaging provision, allows manufacturers to maintain smaller, stable workforces while meeting the same production targets. Their workers can work longer hours during peak periods, balanced by shorter hours in slower months, all while maintaining the same average work week.

References

International Trade Centre. (n.d.). Trade statistics for international business development

Malcolm Owen. (2024, May 16). iPhone 16 displays production starting on time in June. AppleInsider.

Park, S., Yaduma, N., Lockwood, A. J., & Williams, A. M. (2016). Demand fluctuations, labour flexibility and productivity. Annals of Tourism Research, 59, 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.006

Straits Times. (2024, September 20). Apple’s iPhone 16 launches to cheers and applause as hundreds queue outside Orchard Road store. The Straits Times.

The Economic Times. (2024, September 20). iPhone 16 Sale starts today: People queue in large numbers outside Apple stores. The Economic Times.

The Economic Times. (2025, January 2). Mahindra & Mahindra and Tata Motors claim Rs 246 crore as production linked incentive (PLI). The Economic Times.

Times of India. (2025a, January 12). Budget 2025: How can govt enable ease of doing business in India? CII presents 10-point plan. The Economic Times.

Times of India. (2025b, January 21). Make in India goes global with Maha Kumbh. The Times of India.

Shubho Roy and Arjun Krishnan are researchers at Prosperiti.

Appreciate the illustration, would love to see more of this. Usually, the post can be a bit too technical for some