#32: Licence to create jobs

Using administrative data to redesign contract labour law may benefit all

India faces significant shortages in key public service roles. The police force, healthcare system, and administrative offices all suffer from understaffing. The All India Services, representing the top tier of the bureaucracy, faces a 20% shortage compared to sanctioned strength. These staffing deficits extend to regulatory bodies, creating a widespread challenge across the public sector: —the regulatory apparatus must oversee a vast economic landscape with limited resources.

While regulators have created abundant regulations, they lack the capacity to enforce them effectively (Rajagopalan & Tabarrok, 2019). This outcome is the result of a one-size-fits-all regulatory approach, which distributes administrative resources equally across all regulated entities. On the surface, this approach simplifies enforcement decisions and protects regulators against accusations of bias. In reality, it ends up burdening compliant entities, while failing to adequately address non-compliance.

Labour regulations is an example of this one-size fits-all approach. On the one hand, labour compliances account for 47% of all business regulatory requirements and are shown to increase the cost of labour by 35% (Amirapu & Gechter, 2020; TeamLease RegTech, 2023). On the other hand, only 644 working inspectors are available to oversee compliance 3,21,578 factories, with each inspector overseeing around 500 factories (Directorate General Factory Advice Service & Labour Institutes, 2023). Even if all vacant posts were filled, each inspector would have to check 337 factories a year.

How do we improve the design of labour laws given resource constraints? The answer could lie in systematically using administrative data. State labour departments already collect a vast amount of data in the form of registration and licence applications, inspection reports, incident reports, and returns. In this article, we show how administrative data collected by labour departments can shed light on reform opportunities. Using this data, we are able to identify marginal improvements in the design of contract labour licensing that may yield outsized impact on both compliance and ease of doing business.

Contract labour licences: A problem

Workers hired through labour contractors constitute around 40% of the formal workforce in India (Directorate General Factory Advice Service & Labour Institutes, 2023). The welfare of contract workers is regulated under The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 (the Contract Labour Act) through the licensing of contractors.

Labour contractors supplying more than the threshold limit of workers per work order must obtain a separate licence under the Contract Labour Act. This threshold is typically set at 20 workers or more per work order in most states. To get the licence, contractors must provide information about the nature of work, duration, and number of contract workers to be employed for each work order. This licence is the same for all labour contractors, irrespective of size, nature of work, number of workers employed, or years in operation.

The evolution of the contract labour industry has created significant challenges for enforcing the Contract Labour Act. In the past, the contract labour market was dominated by small players supplying few workers to service small work orders. Today, contractors supply workers for large-scale public works projects and industries like mobile phone manufacturing, not to mention facilities management and security services. Moreover, a new type of labour supplier called a staffing firm has disrupted the industry.

The Contract Labour Act's requirement for licensing each work order separately has generated enormous regulatory burden given the changes in the industry. Inspectors now face the infeasible task of inspecting every deployment in this expanded industry, while labour contractors face the unenviable task of applying for separate licences, maintaining 7 registers and filing 2 returns a year for each work order.

The data

Analysis of the data on contract licences from one Indian state helps identify solutions to these inefficiencies. The data covers an eight-year period, with a regulatory change in the middle.

What does the data show?

Over the eight-year period, the number of contract workers grew by 350%, from 35,683 in the first year to 1,62,273 in the eighth year. Cumulatively, 9,93,622 contract jobs were created in this state in the eight-year period. These workers were supplied by 6,309 unique labour contractors under 8,992 separate licences.

This translates to an average of 1,24,202 workers through 1,124 licences per year. Roughly,110.5 workers were employed per licence on average while the median number of jobs per licence is ~52. The distribution of workers per licence is skewed to the left, indicating the market has many small labour contractors deploying few workers each (Figure 1).

Contractors that obtained licences for employing 100 workers or less provided 3,23,461 (33%) of the total contract workforce across eight years. Contractors that employed workers between 100 and 500 workers supplied 4,40,488 (44%). Contractors that obtain licences for employing 500 workers or more provided 2,29,713 (23%) of the contract workforce (Figure 2).

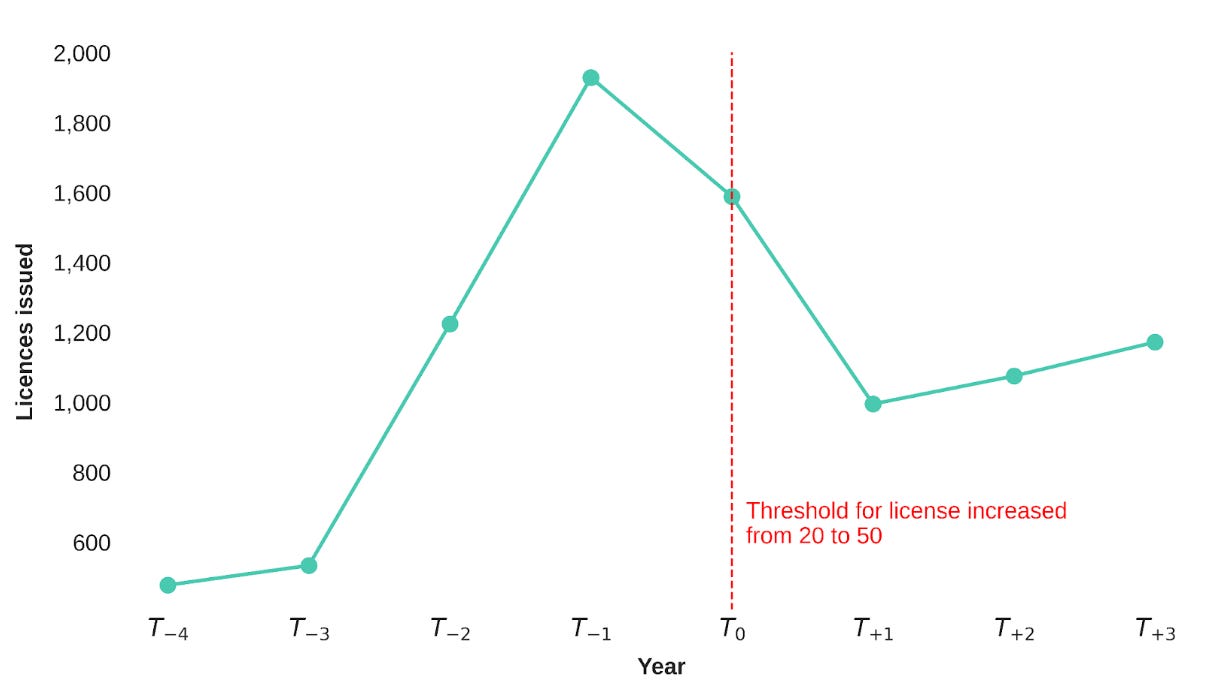

Another feature of the data is that it captures a natural experiment. In the fifth year (T0), the state changed the threshold to obtain licences. Previously, contractors supplying more than 20 workers in any single work order had to obtain a licence for that work order. In the fifth year, this threshold increased to 50. As expected, the number of licences fell after the legal change (Figure 3).

However, the natural experiment of changing the threshold did not reduce the number of workers covered. Even after the threshold more than doubled, the total number of workers covered by the law continued to increase. In the year after the threshold change, the number of workers fell by ~20%, but thereafter reached a new peak (Figure 4).

How can we use this data to guide reform?

Regulators can use this administrative data to understand the efficacy of regulations. In the case of the implementation of the Contract Labour Act, three clear solutions stand out: establishing higher thresholds for licensing requirements, implementing consolidated licences for larger contractors, and extending licence validity periods.

Increasing applicability thresholds

Labour contract licensing thresholds are set too low. The low threshold speaks to a time when the sector was not critical to labour supply. Recognising this, at least 14 states have raised their thresholds from 20 to 50.

In our particular example, increasing the contract licensing threshold from 20 to 50 did not reduce the number of workers protected. In fact, raising this threshold further to 100 would let regulators oversee 70% of the current contract workforce while monitoring half the contracts (Figure 5).

The proposed change offers several benefits. First, smaller contractors would face reduced regulatory burden, potentially encouraging growth in this sector. Second, regulatory bodies could concentrate inspection resources on larger contractors, who employ most of the contracted workforce. Low thresholds may create the opposite outcome of what the government seeks to achieve as it attracts players who excel at navigating complex rules and discourages efficient and ethical businesses. Given the paucity of inspector resources, it may be better to focus enforcement attention on an even more select group.

Delineating licences from work orders

Currently, a single employer may be required to obtain multiple licences for contract labour each year. This is because the law requires contractors to apply for separate licences for each work order. In one instance, a contractor applied for 19 licences in a single year to supply 3,700 workers.

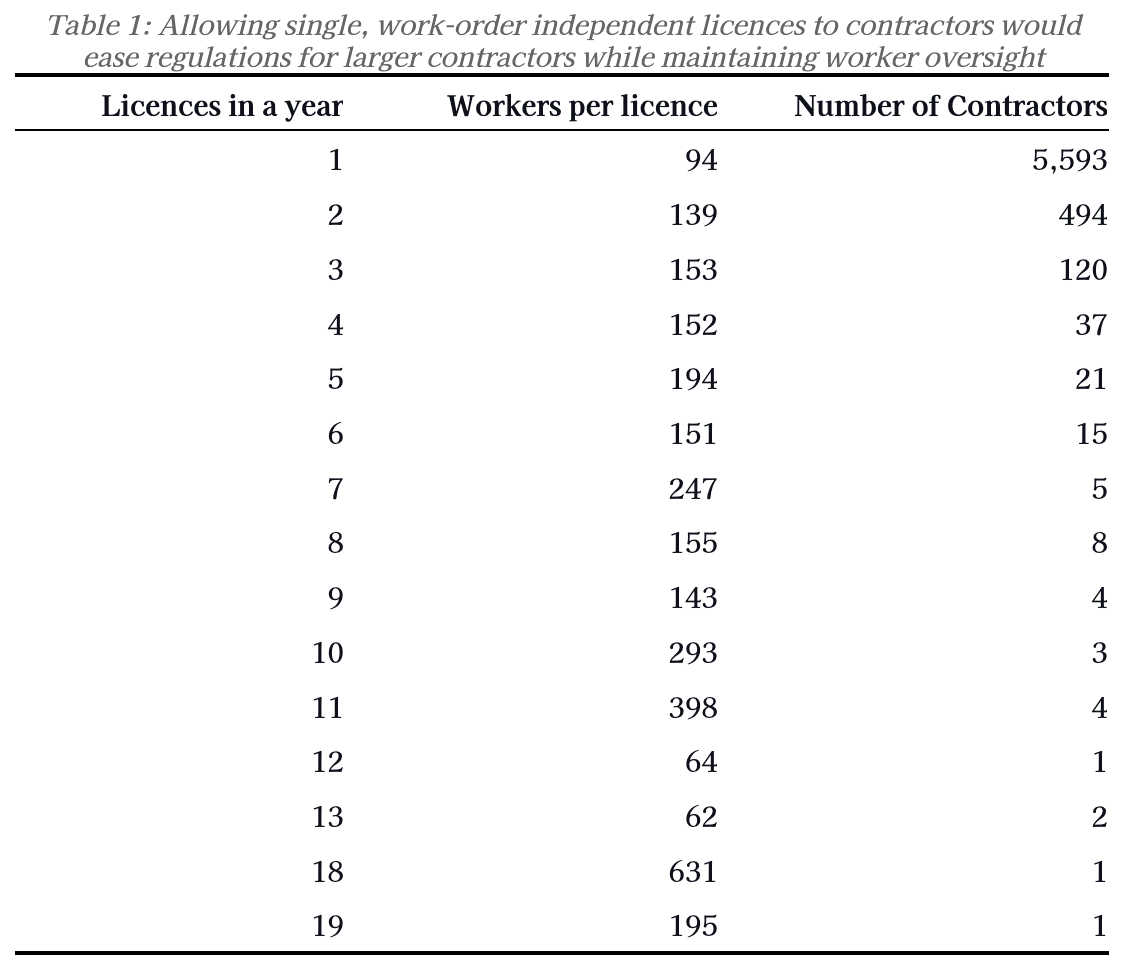

Another approach is to encourage players that obtain multiple licences in a year by offering a general licence. The data shows that the labour contractors that obtained more licences each year created more jobs per licence. Larger contractors (with more than 7 licences a year) employed 237 workers per contract on average, compared to smaller contractors (who obtained fewer than 7 licences in a year) who employed 106 workers per contract on average (Table 1).

A general licence would allow businesses to consolidate returns and registers to be maintained. For the government, a single licence would have reduced the number of licences by 2,240 (25%) over the eight-year period. This reform would not reduce oversight on workers since all workers would still be supplied by contractors with a licence.

Longer licences

Licences for labour contractors are valid only for one year. This means that contractors need to reapply for a new licence for each year they stay in business, regardless of their operational history or compliance record.

This finding can be used to put greater regulatory emphasis on contractors operating for 2 years or less. In our example, labour contractors working for 3 or more years created 30% of the jobs over the eight-year period, while labour contractors working for 2 years or less provided the bulk (70%) of the jobs. Of the 6,309 contractors, 822 (13%) operate for multiple years. Contractors that operated for a single year employed a mean of 89.7 workers, while contractors that operated for all eight years employed an average of 550.2 workers. Such an approach still keeps the majority of jobs under regulatory scrutiny while reducing the compliance burden on the long-term players.

Multi-year licensing for established contractors would allow regulators to concentrate oversight on newer, less established operators while reducing the administrative burden on long-term contractors. Reduced compliance costs would free up resources for business growth and potentially better working conditions. Moreover, regulators could focus their limited resources on monitoring smaller, potentially riskier contractors who may be more prone to non-compliance. At a system level, this change could incentivize currently unestablished players to grow and maintain compliance, rewarding them with lower regulatory burdens as they become more established. This approach to regulation has been recognized in the proposed Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (OSHWC) Code, which allows for a five-year contractor licence [S. 48(3)].

Conclusion

Administrative data can help departments recognise the level of risk posed by different regulatees and redirect their efforts based on this risk. There are two approaches to risk-based regulations. The common approach is to allocate enforcement resources based on risk. In some sectors such as police patrolling and traffic management, such data is already being used for targeted regulatory action. The more uncommon approach is to use data and risk analysis to draft and redraft rules so they are more targeted.

Redrafting rules using administrative data insights could help policymakers to achieve the dual goals of effective oversight and prosperity. The shortage of public sector inspectors in particular limits oversight of regulated industries. Risk-based regulation offers regulators with limited capacity a pragmatic solution to their challenges. Regulators can prioritise their efforts by focusing on higher-risk entities or newer market entrants. This targeted approach enhances the effectiveness of oversight while reducing unnecessary burdens on established, compliant entities. As a result, regulators can foster a more dynamic business environment without compromising worker protections.

Risk-based targeted labour rules can deliver similar results as the current approach of broad coverage rules, but at a lower cost for both the regulated and the regulator. For the regulated, this means reduced compliance burden and less risk of harassment. For the regulator, it means a high level of protection with fewer resources. The analysis above shows that the labour regulator could achieve the same or similar levels of protection for workers with fewer regulatory filings.

In a context where growth is crucial for poverty reduction, intelligent regulation becomes paramount. By evolving their regulatory strategies, policymakers can address the dual challenges of protecting workers and promoting economic progress.

References

Amirapu, A., & Gechter, M. (2020). Labor Regulations and the Cost of Corruption: Evidence from the Indian Firm Size Distribution. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 102(1), 34–48.

Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act. (1970).

Directorate General Factory Advice Service & Labour Institutes. (2023). Standard Reference Note—2022. Ministry of Labour & Employment, Government of India.

Rajagopalan, S., & Tabarrok, A. (2019). Premature Imitation and India’s Flailing State. The Independent Review, 24(2), 165–186.

TeamLease RegTech. (2023). Compliance 3.0—Beyond Accidental Compliance.

Bhuvana Anand, Shubho Roy, and Arjun Krishnan are researchers at Prosperiti. The authors thank Abhishek Singh for his insightful recommendations on key aspects and relationships to explore in our dataset.

Very good ideas!

What is not dealt with is the efficacy of the contract labour law. What does the licensing and record-keeping result in as far as the individual contract worker is concerned? Have there been many prosecutions against contractors? Which size of contractor? Is there a marked difference between the working conditions and pay of the licensed contractor's workers and those of the small and unlicensed contractors?