The 2024 budget, presented on 23 July, has added emphasis to manufacturing to accelerate India’s economic growth. Paragraph 23 of the budget speech states:

“We will facilitate higher participation of women in the workforce through setting up of working women hostels in collaboration with industry, and establishing creches.”

Hostels near workplaces offer benefits like shorter commute times and improved productivity. Sadly, Indian workers cannot live next to their jobs because of legal restrictions contained in zoning laws called Master Plans. These Master Plans prohibit the construction of essential worker hostels within industrial zones. This disparity not only limits residential options for workers but also undermines potential gains in productivity and industrial efficiency.

Zoning regulations prevent worker housing in some jurisdictions

Many Indian workers cannot be provided such accommodation because of legal restrictions placed at the local level. Of the nine jurisdictions studied by Prosperiti, only three allow workers to live in industrial areas.

These locations prohibit worker accommodation through Master Plans, a legal instrument used to control the development of cities. An example of this plays out in Uttar Pradesh’s leading industrial hub, Noida. Noida’s Master Plan for 2031 plans to develop 2,806 hectares of land for industrial use but prohibits worker housing within these zones.

The table shows that worker hostels cannot be constructed in industrial zones. This discrimination is against industrial areas specifically. This bias indicates that nearly a fifth of the city, where the highest industrial production occurs, cannot build worker housing units. These regulations are arbitrary as they allow guest houses and lodges in industrial zones, but bar hostels. These buildings house workers and, therefore, pose similar risks to safety and health.

Similar restrictions are also in place in Punjab’s S.A.S. Nagar. Like Noida, workers cannot stay close to their places of work due to the S.A.S. Nagar’s Master Plan for 2031.

The Master Plan prohibits dormitory or hostel development in industrial zones.

Noida and S.A.S Nagar are relatively older developments. Unfortunately, even proposed cities continue with restrictions that enable affordable housing for industrial workers. An example of this is Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh’s capital, which bars hostels from industrial areas.

In Amaravati, while worker hostels in industrial zones are prohibited, they are allowed in commercial zones. Amaravati’s zoning regulations expressly prohibit the development of ‘hostels’ in all three types of industrial zones. Industrial zones in Amaravati will allow some workers to stay near their place of work through a different type of residential building called—workers quarters. However, these quarters are allowed to be constructed only after acquiring a separate conditional use permit. Under this permit, the authority can “impose conditions and safeguards as deemed necessary to protect and enhance the health, safety and welfare of the surrounding area” (Rule 214: Conditional Uses, page 32). The permit expires if it is discontinued for a period of one year. Incidentally, neither ‘hostels’ nor ‘worker quarters’ are defined terms in the regulations.

Industrial areas in Belgavi, Ludhiana, Nava Raipur, and Kakatiya also prevent worker hostels from being constructed.

Some exceptions

Some industrial areas in India are the exception, allowing worker hostels close to where the jobs are. These areas include Delhi, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal.

Workers hostels were specifically mentioned in Tamil Nadu’s its 2021 industrial policy:

“Industrial projects will be encouraged to develop accommodation and hostel facilities for employees within a 5 km radius of the work area” (page 13).

Reflecting this industrial policy, workers' hostels have been allowed in Tirunelveli’s Master Plan for 2041, which allows worker hostels in industrial zones. The Master Plan permits worker hostels in industrial use zones:

The Master Plan states that in industrial zones will permit:

“...residential, commercial, and institutional and other activities” (page 406).

Tamil Nadu’s legal changes are also leading to changes on the ground. In Sriperumbudur, a 60,000-worker hostel is coming up close to the manufacturing unit. Similarly, a government-led 15,000-worker housing project is being constructed in the same town. In addition, the Tamil Nadu government has commenced work on the Sriperumbudur belt. These facilities will be rented out to industries and their workers.

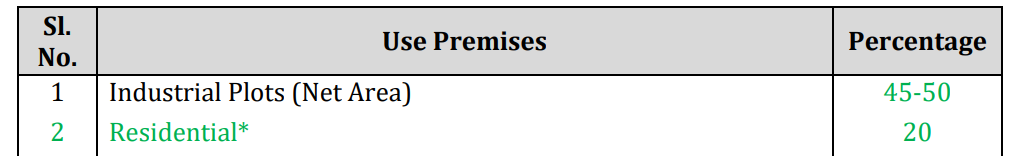

Similarly, Delhi’s Master Plan for 2021 reserves 20% of industrial areas for residential activities.

The Delhi Master Plan states, on page 103, that residential development in industrial zones will provide housing for industrial workers:

“In case of residential use premises regulations for Group Housing shall apply. The land shall be reserved for facilities as per residential facilities. This housing would be for workers engaged in the industrial sector.”

The 2023 Master Plan of Durgapur, West Bengal similarly allows hostels in industrial zones.

Increased commute distance is detrimental not only to workers but also to the industries. A long commute creates car-dependent communities, consumes more resources, land, and energy per capita, resulting in higher infrastructure costs and environmental impacts (Bahadure & Kotharkar, 2012).

India’s worker housing has historic roots

India’s ban on worker hostels is new. In the past, India has also used worker housing to support areas where industrial growth outpaced urban growth. An example of such housing is Bombay’s chawls, a response to the influx of workers to India’s industrial powerhouse in the first half of the twentieth century. The population of Bombay shot up from 25 million in 1901 to 35 million in 1951. During this period, Bombay overtook Calcutta as India’s premier financial and industrial hub (Agrawal, 2017). Chawls helped augment Bombay’s industry-led development in the early 1900s. These chawls were constructed as housing structures by the industries, the State or as private investments. A collection of such buildings would create a colony of migrant workers (Sanyal, 2018).

Research by Chauhan (2023) highlights Delhi's similar development of worker housing colonies, paralleling the rise of industrial enterprises. The city witnessed a boom of small and medium-scale industries in the mid-20th century, which naturally drew industrial workers from other states. This influx of workers prompted the Delhi Master Plan of 1962, which ordered industries to relocate to the city’s outskirts. The resultant demand for worker housing was responded to by single-room housing complexes, which industrial workers rented on long-term leases.

Concerns

There are some concerns about building worker hostels near the workplace. Freedman et al. (1997) observed that workers who lived close to their workplace faced higher environmental concerns. The workers experience a higher cost of living due to traditional work areas being ill-equipped to support residential life. Workers may end up overworking themselves, too, as they feel obliged to work during their downtime as well. Allowing residence in industrial areas may also be accompanied by antisocial behaviour in low-income neighbourhoods (Bahadure & Kotharkar, 2012).

Considerations for policy making

Even with the demerits of worker hostels, should the law completely ban them? The answer is probably no. Worker housing might be a temporary phenomenon in response to times when industrial growth outstrips urban growth. In other locations it may be the most efficient way to generate wealth despite failures of urban infrastructure.

Banning worker hostels removes options for industries and workers. The bans do not contribute to the solution in any way, as bans do not spur the growth of other forms of urban housing or make homes in cities cheaper. Instead, the Indian restrictions may be coming in the way of workers moving out of poverty through industrial employment.

Removing restrictions on worker hostels merely generates an option for industry and workers. It may not be suitable for all industries at all locations. However, we should consider keeping all policy options open to encourage Indian prosperity.

References

Agrawal, A. (2017, April 6). Why did Bombay takeover Calcutta as the leading financial centre? Some probable reasons…(Part -II). Mostly Economics.

Bahadure, S., & Kotharkar, R. (2012). Social Sustainability and mixed landuse. Case Study Neighbourhoods Nagpur, India, 2(4), 76–83.

Chauhan, E. (2023, July 6). Living in the peripheries: The ignored industrial housing of Delhi. The Indian Express.

Freedman, O., & Kern, C. R. (1997). A model of workplace and residence choice in two-worker households. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 27(3), 241–260.

Jiang, X. Y., Lai, P., & Chan, B. Y. (2022). The Practice and Exploration of Construction Industry Worker Training and Evaluation. International Journal of Advanced Business Studies, 1(1), 44–50.

Ngai, P. (2009). Gendering Dormitory Labour System: Production and Reproduction of Labour Use in South China. In C. Verschuur (Ed.), Vents d’Est, vents d’Ouest: Mouvements de femmes et féminismes anticoloniaux (pp. 129–149). Graduate Institute Publications.

Sanyal, T. (2018). The Chawls and Slums of Mumbai: Story of Urban Sprawl. Agora Journal of Urban Planning and Design, 12, 22–34.

Schmiedeknecht, K., Perera, M., Schell, E., Jere, J., Geoffroy, E., & Rankin, S. (2015). Predictors of Workforce Retention Among Malawian Nurse Graduates of a Scholarship Program: A Mixed-Methods Study. Global Health: Science and Practice, 3(1), 85–96.

The authors thank Sargun Kaur, Anandhakrishnan S, and Shaunak Desai for their contribution.